Mary Receiving Jesus into Her Arms

by Becky Eldredge

Parents across the world understand the emotional moment of receiving our children into our arms for the first time. In an instant, something wells up from deep within us, and in a fleeting range of emotions we experience profound love for another, tremendous responsibility for another, and fear. When Abby, my daughter, was born and placed into my arms those same emotions arose-love, responsibility, and fear.

Advent prepares us for the birth of Jesus. On Christmas, we celebrate the act of Mary receiving Jesus into her arms for the first time-a moment that exemplifies “the Word became flesh and lived among us” (John 1:14). Can we imagine the gaze between mother and child that day? Mary gazing into Jesus’ tiny eyes, stroking his hair, and snuggling the new life in her arms. Mary feeling the same profound love, tremendous responsibility, and fear that all parents experience. Jesus looking up at her. Jesus crying and needing to be soothed by his mother, the same way all newborns need to be soothed.

I know Mary was changed by Jesus’ birth. Advent prepares us for the Incarnation, when a little baby boy brought a light into his mother’s life that changed her life. Advent prepares us for the greatest reason for hope in this world-that this little baby boy brought light not only into his mother’s life that night, but that Jesus’ birth brought powerful light into our world.

A similar dream

In June, a group of Jesuit scholastics and priests spent a week in a Islamic boarding school in East Java, as part of the Indonesian Province’s efforts against religious radicalism, one of three concerns the Province has made a priority. Scholastic Billy Aryo Nugroho SJ recounts his experience.

From June 17 to 23, 16 Jesuit scholastics and two priests lived in Islamic boarding school, pesantren in Indonesia. The pesantren was named “Tebu Ireng” and is located in Jombang, East Java.

The stay in the pesantren is a programme of the Indonesian Province that addresses one of its major concerns, religious radicalism. The other two priority concerns of the Indonesian Province are poverty and environmental damage. The concern around religious radicalism is also confirmed in the documents of the Society of Jesus, particularly during the 35th General Congregation.

We hope that this programme can be a significant contribution to our country, which is now threatened by religious radicalism. We also hope that this programme will help Jesuits in formation to embrace the spirit of religious dialogue. Indonesia is a Moslem-majority country therefore a dialogue with Moslem people is indispensable.

We were accompanied by two Jesuit priests who have worked in this area for some time – Fr Heru Prakosa SJ and Fr Greg Soetomo SJ. Fr Heru is an Ad Hoc Coordinator for Moslem-Christian Dialogue for the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific, while Fr Greg is a coordinator of the Justice and Peace Commission in the Indonesian Province.

During this programme, we lived together with the pesantren’s students who are called santri. Unfortunately, when we were there, it was the holiday period for santris so few of them were there. Nevertheless, we did not lose our passion to live together with them.

The interesting activity during our time with them was having philosophical and theological discussions. We discussed influential figures from both our religions. We Jesuits spoke of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a great philosopher and theologian, while the santris told us about Al-Ghazali (1058-1111), also a great philosopher and theologian. The discussion enriched our knowledge of each other.

However, the most memorable experience was our meeting with the chief of this pesantren, Salahuddin Wahid, usually called Gus Sholah, whose father had founded the pesantren. During that meeting, Gus Sholah shared with us some inspiring thoughts. He said, “We have a similar dream, which is to create prosperity and peace in our country.” He wanted us to collaborate to make this dream come true. What a beautiful thought. We are united by the same dream. By this experience, we can simply say that humanity unites all people, regardless of their gender, race or religion. Indeed, it is our great duty to accomplish this and this duty can be realized only by struggling together.

After experiencing this programme, we are optimistic that there is promise and hope to build a prosperous and peaceful country where there is religious tolerance, since we believe that we are not striving alone. One thing that we can learn from this experience is that humanity unites all and inspires all to spread the benefits of humanity itself among other people around us.

Billy Aryo Nugroho SJ is a second year Jesuit scholastic studying philosophy at Driyarkara School of Philosophy in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Wisdom Story 47

A miser hid his gold at the foot of a tree in his garden. Every week he would dig it up and look at it for hours. One day, a thief dug up the gold and made off with it. When the miser next came to gaze upon his treasure, all he found was an empty hole.

The man began to howl with grief, so his neighbors came running to find out what the trouble was. When they found out, one of them asked, “Did you use any of the gold?”

“No,” said the miser. “I only looked at it every week.”

“Well then,” said the neighbor, “for all the good the gold did you, you might as well come every week and gaze upon the hole.”

Toward the Church’s Social Mission in Asia

by Denis Kim, SJ

Context: Asia in Development

It is a difficult task to describe the quality of democracy in Asia Pacific. A complexity is that Asia-Pacific has many interesting and diverse cases: communist (North Korea), post-socialist (China and Vietnam), post-civil war society (Cambodia), military dictatorship (Myanmar), liberal democracy (Australia). Many countries, such as Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan can be either categorized as illiberal or situated somewhere between liberal and illiberal democracy.[1] In terms of the UN Human Development Index 2011, Japan is ranked as the 12th, Hong Kong as the 13th, South Korea as the 15th, and Singapore as the 26th, followed by Malaysia the 62nd, among the all countries in the world.[2] Most other countries, however, are ranked outside the 100th. In terms of corruption and transparency, similarly, only a few countries receive high rank: Singapore as the 5th, Hong Kong as the 12th, Japan as the 14th, Taiwan the 32nd, followed by South Korea as the 43rd.[3] Therefore, it is well-known that most Asian countries are low in terms of the quality of democracy and its poor governance. Even some countries are notorious for their brutal human rights violations.

Beyond the index, the historical change in the political and economic context of the region is more enlightening. Despite the differences in culture, language, history, and ethnicity, in addition to its geographical arbitrariness, East and Southeast Asia can be understood economically. It has been the fastest growing region in the world since 1965. Its economic growth has commonly been described in terms of a ‘flying geese pattern of economic development’.[4] Japan has taken the lead, followed by the ‘four tiger’ economies (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan), then the ‘little tigers’ of Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand), and finally by the post-communist economies (China and Vietnam). To a lesser extent, Myanmar and North Korea are now expected to follow this pattern. The recent “liberalization” of Myanmar can be interpreted in this line. North Korea is reported to endeavour to imitate the Thai model in which both political kingship and economic development are simultaneously pursued.

Given the context of political diversity as well as the significance of economic development in the region, this article focuses on democracy issues of the “tiger” countries. The rationale for this focus is that many East and Southeast Asian countries belong to this category. Moreover, their politico-economic pattern is anticipated to be more accepted as an “Asian” model alternative to the Western one, grounded in market economy, liberal democracy, and human rights norms. The rise of China seems not only to confirm this alternative model but also to reinforce its diffusion. Interestingly, however, under the influence of enculturation discourse, the Church’s mission has paid attention to the religious-cultural context rather than that of political economy. This article aims to fill the gap by examining the politico-economic context and its implication for the Church’s social mission. It begins to examine the political economy of development, followed by the debate of the Asian democracy. Finally, it ends with its implication on the role of the Church in the region.

Developmental State or Developmental Authoritarianism

In the development of East and Southeast Asia, two characteristics deserve attention in relation to the quality of democracy. One is the role of cheap labour; and the other, the role of the state. Economic development has been mainly driven by labour intensive industrialization. Due to the increasing labour costs of the lead goose, older, more labour-intensive technologies were transferred down from the leader countries to follower ones where cheap labour could be found. This began with Japan transferring technologies to Southeast Asian countries, followed by the four tiger countries doing so. The rise of China is also largely indebted to its industrialization based on cheap and flexible labour, about which one might get a glimpse in the recent New York Times’ article on the Apple’s iPad production.[5]

On the other hand, the role of the state is significant in this labour situation. It differs both from that of the small government in liberalism and from that of the executive committee for the whole bourgeoisie in Marxism. It has played an active role of entrepreneur by planning, moderating the private sectors, and even running the business sectors directly. It also has assisted the TNCs (transnational companies) not only by providing the free-trade zones and tax benefits, but also by controlling labour rights and wage in order for the TNCS to secure cheap labour. Again the New York Times’ article illustrates how Apple has benefited through the exploitive use of labourers in China. The role of the state in East and Southeast Asian countries has received ambivalent evaluations. Surely, the state-driven industrialization has contributed to delivering the country out of poverty. However, it was accomplished by authoritarian regimes who disciplined labourers with carrots and sticks. Such regimes include not only post-socialist China but also the four tigers. Those who emphasize the former aspect, entrepreneurship, call these Asian states a “developmental state”; however, those who stress the latter, authoritarianism, name these states “developmental authoritarianism.”

The ambivalent evaluation sets the background for the well-known controversies on the “Asian values” and the universality of human rights. Before this article shall examine them, it is noteworthy that the following shadows of the rapid economic development are commonly pointed out in the region: the reservation of human and labour rights, the development of efficiency-driven bureaucracy, the superiority of the state over civil society, environmental degradation, etc. Industrialization has also resulted in the increase of inequality between its beneficiaries and those who are excluded from its benefits, for instance, between the emergent middle class and the working class, and between those regularly employed and those irregularly employed. The dynamic relationship between the two unequal sides has influenced the political landscape, and thereby the quality of democracy in the region.

Western Democracy or Asian Democracy

The East and Southeast Asia region constituted a significant part of the wave of democratization in the 1980s, together with the fall of communist countries. Countries from the Philippines and South Korea to Thailand and Taiwan became democratized by peoples’ power, and optimism prevailed that the authoritarian regimes would fade away in this wave. However, in the early 1990s, the so-called “Asian values,” in particular, vocally raised by then Singaporean and Malaysian Prime Ministers, challenged the Western liberal democracy. They advocated for an authoritarian discipline, presenting the “Asian values” as a cultural backbone in which hard work, frugality, discipline and teamwork can be generated. Soon, however, the 1997 Asian economic crisis blew up the triumphant presentation of the “Asian values”. They, once acclaimed as an engine for the Asian development, are now identified as a source of crony capitalism used to justify the absence of democratic checks and balances. Nevertheless, partly due to the rise of China and partly to the frustration of economic insecurity following upon de-regulation policy, people observe recently the resurgence of the “Asian values” and the spread of nostalgia for overthrown dictators, and a softening of the memories of autocratic rule among the middle class. In this context, a few years ago, Time, an American magazine, reported “Asia’s Dithering Democracies” in its New Year edition.[6]

Western observers point out several areas in which the Asian countries need to deepen democracy.

· Political culture: Citizens should cultivate their citizenship, differing from subjects or clients who depend on their ruler or patrons.[7]

· Institutions to check and balance power: Society should develop its independent institutions, such as media and court, which can check power.

· Political society: Political parties should represent the diverse interests and are able to mediate people with the state.

· Civil Society: Especially, public sphere should be independent from the state’s control and needs to be strengthened

These observations are based on the Western liberal democracy model. Those who believe that the Western model is not universal argue for Asian democracy. There is no definite consensus on the Asian values or a model of Asian democracy. However, it tends to stress the following aspects:

· social harmony and consensus over confrontation and dissent

· socio-economic well-being instead of liberal and political human rights

· welfare and collective well-being of the community over individual rights.

Sometimes it is presented as Asian communitarians over individualism and liberalism, together with the emphasis on nation or state over individuals. Therefore, it is no surprise that authoritarian regimes in Asia have used similar logic in order to justify their authoritarian exercise of power and repress political dissent. Moreover, this logic has been employed in the human rights controversy with regard to China, contending that human rights norms are a Western moral weapon to tame Asia by imposing their standard on Asia.

Despite cultural or political logic, the claim for the Asian mode of democracy can be made on the ground of the Asian state’s performance in development. Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father who built the modern affluent Singapore out of the de-colonized small city country with no natural resources, is bold to argue for Asian values. While constructing Singaporean capitalist development, he used to compare socialist with capitalist regimes. However, since the 1990s, he assesses countries by contrasting those possessing Asian values with those that do not. Invited to Manila where democratization took place in 1986 but the economy still suffered, He asserted “Contrary to what American commentators say, I do not believe that democracy necessarily leads to development. I believe that what a country needs to develop is discipline more than democracy. The exuberance of democracy leads to undisciplined and disorderly conditions which are inimical to development” In his view, the Philippines is handicapped both by its “American-style constitution,” which undermines social discipline and stability, and by its “lack” of Asian values. These two factors account for the country being less successful than other developing Asian countries. “The ultimate test of the value of a political system is whether it helps that society to establish conditions which improve the standard of living for the majority of people, plus enabling the maximum of personal freedoms compatible with the freedoms of other in society.”[8]

Lee’s assertion on Asian values has not only met Western criticism, but also Asian critiques as well. Above all, another Asian leader, Kim Dae Jung, later Nobel Peace prize winner and President of South Korea, refuted these advocators of the “Asian Values.” He argues that Asian cultural traditions support not only economic development, widely argued in the Confucian work ethics, but also political democratization, by pointing out in Mencius the people’s right to overthrow a tyrant. This reveals the diverse interpretations of the so-called Asian traditions.

The debates on the “Asian values” manifest several layers in the changing landscape of East and Southeast Asia. Above all, Lee and Kim represent top Asian political leaders. Lee has built Singapore, and it makes him credible. In contrast, Kim, as a political dissident, fought against Dictator Park with whom Lee shared similar political philosophy and style. Lee himself explicitly admired Park as the modernizer of Korea in his autobiography. The difference between Lee and Kim, thus, is natural. Successfully presenting himself as a democracy advocator, Kim finally won the Nobel Peace Prize after the summit conference between North and South Korea. In this sense, the debates on the “Asian values” have been rather politically constructed and presented by politicians’ raiding the rich storehouse of Asian cultural and religious traditions. The differences internal to Asia and their dialogical and dialectical development within Confucianism, Buddhism, or Islam have been ignored or merely selectively emphasized.

The Asian value debates reveal not only pride in what Asian countries have accomplished, but also a claim to superiority, at least in culture and morality, if not yet in economy, over the West, the former colonizers. Their advocates commonly point to the shadows that reveal the limits of Western modernity, such as racism, excessive individualism, rising crime and divorce rates. However, it is misleading to interpret the debate on the Asian values in the binary frame of “Asian” versus “Western” democracy. Samuel Huntington, a former Harvard political scientist, suffers this pitfall when arguing for the “clash of civilization.” His thesis essentializes the Orient as the symbolic opposite of the West and overlooks the political-economic structure that supports the difference and difficulties. In doing so, both the Asian value advocates and Huntington orientalize Asian traditions as timeless and irrefutably embodied in all Asians.

Rather than the civilizational difference, the Asian value debates can be better understood, as Aihwa Ong, a Berkeley anthropologist, points out, as the “legitimization for state strategies aimed at strengthening controls at home and at stiffening bargaining postures in the global economy.”[9]In other words, the difference between East and West can be better understood in the context of neoliberal globalization. Whereas American neoliberalism undermines democratic principles of social equality by excessively privileging individual rights, the dominant Asian strategy in the global market undermines democracy by limiting individual political expression by excessively privileging collectivist security. The recent nostalgia for authoritarian leaders illustrates that the emergent middle class, the main beneficiaries of economic development in these tiger countries, demands better government not so much in terms of democratic representation as in terms of the state’s efficiency in ensuring overall social security and prosperity.

Nation-State and Migration

The state-led development and its success have shaped the move of people. After decades of economic development, the leading economic powers in East and Southeast Asia, such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, have become target countries for immigrants, and thus the international migration has rapidly increased within the region. Obviously, the typical causes of international migration between the North and the South, such as the difference in economic structures, life expectancy, demography, social conditions and political stability, can also partly explain this regional migration.

The characteristics of state-led development, however, illustrate a different pattern of social exclusion from Western immigration countries. In terms of ethnicity and race, except Singapore and Malaysia, the receiving countries in the region are highly ethnically homogenous: 98% Koreans in Korea, 98.5% Japanese in Japan, 91.5% of Han Chinese in China, and 98% Han Chinese in Taiwan. It is not surprising that the citizenship law is based on ius sanguinis and that foreigners are not treated as equal. In other words, the fault line between ‘us and them’ is easily drawn in blood lines. It partly explains the nationalistic culture in these countries. State is conceived as an extension of family, and nation is a state. Therefore, foreign people easily become subjects the state pays attention to, takes “care” for and controls for the state’s agenda, which is usually interpreted as the national agenda. It is a consequence of a state which not only has orchestrated the economy but also has organized the whole society for economic development. Furthermore, these countries are proud of being a mono-ethnic country, and ethnic minorities have been easily ignored in the name of the national good. Korean descendants in Japan and Chinese descendants in Korea have long been discriminated against and marginalized.

In summary, focusing on the tiger economies in the region, this article has addressed economic development, in which the state has played a crucial role, as the main common characteristic of the region. The promotion of authoritarian leadership or Asian democracy manifests not only their pride in their accomplishment, but also their mode of social regulation, which can ensure continuing economic development while minimizing socio-political cost. Obviously, as stated earlier, these characteristics are different from North Korea, Myanmar or some other countries. However, the rise of China is anticipated to affirm and reinforce the diffusion of state-led development, together with its social regulation, in the region.

Toward the Church’s Social Mission

The political, economic context of East and Southeast Asia charges the Church to rethink its social mission. The reception and creative appropriation of the CST(Catholic Social Teaching) seem to vary among the local churches. Two factors, one internal and one external, may explain the variance of their reception. Internally, the “inculturation” discourse has led the church to focus on culture or religion. In spite of the importance of sensitivity to local culture, emphasized since Vatican II, however, the efforts toward inculturation have not been free from the danger of essentializing culture in a dualistic way, such as the civilizational discourse does. Some inculturation discourse assumes the so-called modern, Western, capitalistic culture to be bad whereas local culture is romanticized as a source of identity-giving. However, the West “is now everywhere, within the West and outside: in structures and minds.”[10] In practice, there is no pure local culture untouched by Western modernity. Inculturation can be void if it lacks analysis of political and economic context and the appropriate response to this context. Externally, the church is a minor religion[11] in a society where the state is a strong regulator. Thus, it has often been considered risky for the church to engage in public issues. This has resulted in the Church’s social mission being easily confined within the religious and spiritual realm and within the boundary of the pre-existing nexus between state and society, rather than implementing the CST challenges.

It is ironic, however, that the churches socially engaged for the common good have been more successful at gaining conversions in Asia. The fastest growing churches for the past half century in the region are those in Timor Leste and South Korea. In Timor Leste, the Catholic population has grown from about 25% in 1975 to 98% in 2005, whereas its counterpart in Korea has grown from about 3% in 1960 to 10.1% in 2010, an exceptional phenomenon in Asia. Despite the difference in the historical context and the social location of the churches, the common characteristic of the Catholic Church in both countries lies in its contribution to the historical task in their countries. The task for the former was decolonization from Indonesia; the latter, democratization. The former Bishops Belo in Dili, Timor Leste, and Cardinal Kim in Seoul, South Korea, responded to this historical task with the spirit of the Gospel and Vatican II despite high risk. Due to the leadership in and contribution to these historical tasks each has been counted as one of the most respected persons in their respective countries. As a result, the Catholic Church in both countries has enjoyed moral authority, perhaps a more important quality to any religion than political and economic resources. More importantly, although people know its Western origin, the Church is no longer perceived as a foreign religion. The transformation of its perception has taken place in both countries, because the Church has taken a significant part in their historical change. A true inculturation!

The Church in the region can learn the lesson from the historical experience of Timor Leste and South Korea. It is the Church’s contribution to the historical task of the larger society. Cardinal Kim asserted that the raison d’être of Church is not for its own sake, but for the good of the larger society and strove for its implementation in spite of internal and external opposition. Especially in a society where the state tries to domesticate society and present itself as an agent of national good, the role of the Church becomes more significant and has more potential. It should define the common good in its own context, a context where the state usually defines the national good differently from the CST. In a globalized world, the Church as a transnational institution can find favourable space and resources more easily than before to counterbalance the state and build networks for the common good. Jesuits as members of a global religious order can make many paths to serve for the Church in Asia in defining the common good, making strategic plans for it, and mobilizing and connecting the people and resources so that they can be implemented.

[1]Cf. Fareed Zakaria, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Foreign Affairs, November/December 1997.

[2]http://hdr.undp.org/en/data/trends/

[3]http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2011/dec/01/corruption-index-2011-transparency-international

[4] Kasahara S. (2004) “The Flying Geese Paradigm: A Critical study of Its Application to East Asian Regional Development,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Discussion Paper # 169, April. Mitchell Bernard and John Ravenhill (1995). “Beyond Product Cycles and Flying Geese: Regionalization, Hierarchy, and the Industrialization of East Asia.” World Politics 47, pp 171-209.

[5]New York Times “In China, Human Costs Are Built Into an iPad” (Jan. 25, 2010) http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/26/business/ieconomy-apples-ipad-and-the-human-costs-for-workers-in-china.html?ref=applecomputerinc

[6]http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1869271,00.html#ixzz1kcaURiND

[7] Cf. Robert D. Putnam, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton Univ. Press, 1993).

[8]Far Eastern Economic Review, 10 December 1992. Quote from Aihwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship (Durham, NC: Duke University) 1999, 71.

[9]Ong, op. cit., 11.

[10]Quote from A. Escobar, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995) 224.

[11]In East and Southeast Asia, only the Philippines, Timor Leste, South Korea and Vietnam have Catholics more than 5% of its total population.

Faith Adrift

The wondrous ‘Life of Pi’

by Karen Sue Smith

Put on a pair of 3-D glasses and treat yourself to the sensuous Life of Pi, a film that offers viewers a succession of unforgettable screen images, beginning with a parade of exotic animals seemingly filmed in Eden. Other scenes depict terrifying thunderstorms at sea; starlit night skies of cosmic grandeur; glowing, undulating creatures, inhabitants of a mysterious underwater world; a whale leaping in an exuberant arc out of the ocean depths; and sunlight bouncing off the mirrored surface of an ocean becalmed.

Ang Lee has taken Yann Martel’s acclaimed philosophical/psychological novel about a zookeeper’s son who survives a shipwreck alone on a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger, and has animated it through ingenious effects, including a digitally enhanced tiger. But Lee (director of “Brokeback Mountain”) has done much more than assemble astonishing images. Namely, he has carefully preserved the underlying tensions and thought-lines that make this story provocative, relevant and even important in our day.

For despite its trappings as an adventure story or a coming-of-age journey, Yann Martel’s 2001 novel, which won Britain’s Man Booker Prize for fiction, lays out the religious side of the ongoing argument between science and religion, atheism versus belief. Rather than arguing his points, however, head-to-head in a classroom or through dialogue, as in the film “My Dinner With Andre,” Martel creates an appealing character who embodies faith, a young Hindu-Catholic with an interest in Islam and Judaism, too.

Piscine Molitor Patel is a modern Job figure. Don’t be thrown off by his name-from a swimming pool in Paris-one of many bits of humor in this serious, powerful story. You have to be introduced to faith, Piscine says, ever wiser than his years.

Lee’s film introduces us to faith through a screen hero so atypical as to be a kind of anti-hero. Pi, a self-made nickname pronounced like the mathematical constant 3.1416, shows how a believer responds to life, including its immense suffering. Though he loses his beloved parents and brother in the shipwreck, endures months without human companionship, undergoes injury, starvation and thirst, he survives without losing his faith. Indeed, Pi’s habit of gratitude to God-for his own life and for that of this marvelous universe-never wavers.

Suraj Sharma, in the title role, gives the teenage Pi a natural winsomeness, both innocent and knowing, that sustains our attention. Unlike a typical adventure hero, this 16-year-old does not fight the tiger and emerge the victor. Instead, he is a vegetarian animal lover, a studious reader and to his marrow a man of peace who says he is sorry when he kills his first fish. When the young Pi tells his father he believes animals have souls, his father urges him to rely on reason. On the lifeboat Pi heeds his father’s advice, using reason to train the tiger and subdue it, so that the two of them can survive. But survival is not his only concern. Pi fishes relentlessly in order to feed the tiger, when he might have killed it or at least let it drown and saved himself the effort. Once, when the tiger (whose name, for another laugh, is Richard Parker) plunges into the ocean and cannot get back into the boat, Pi thinks it over and makes him a ladder. Finally, in one pietà-like image, when Pi thinks they are both dying, he places the tiger’s head on his lap and strokes it. Few superheroes would claim, as Pi does, that Richard Parker actually saved his life.

We are helped to suspend our disbelief by the opening scenes. Pi is not just any boy, but a Hindu who has grown up with animals, the very animals his zoo-owning father has had packed onto the freighter on which he and his family are sailing across the Pacific to seek a new life in Canada. Pi has spent years getting to know Richard Parker and Orange Juice, the female orangutan who takes shelter on the lifeboat, along with one of the zoo’s zebras and a hyena, in the early lifeboat scenes.

Pi is also intelligent and resourceful, the kind of person who would scour the boat for supplies, read and reread the survival manual, be disciplined about eating the rations and purifying drinking water. He is a problem-solver, a boy able to build himself a life raft out of life jackets and boards, and he is an accomplished swimmer. Pi has shown internal fortitude, too, in seeking Christian baptism, for example, despite the contrary views of his uncle and father.

Few films based on novels can maintain the complexity of the printed word, but they may not need to. Directors can edit to help propel the story forward, which is what Lee has done. The story’s quickened pace and simplification-the removal of encyclopedic passages about animal behavior and the slow motion violence of the hyena’s attacks and demise, for instance-make the religious questions stand out more clearly. Lee has kept the novel’s framing conceit, so that in the opening and closing scenes viewers look on as the adult Pi tells his story to a writer. Especially in the final scenes, this device, which seems to let Pi step right out of the story, works. By this time we have heard two different stories. The second one sounds like a newspaper account about the survivors of a shipwreck, darkened by human brutality and their reaction to it. That story has few surprises and no animals, but could be true to the facts.

Just as Pi asks the writer to whom he has entrusted his tales, Lee asks us to choose which story we prefer. We are invited to step into the story ourselves. We have seen Pi’s example and we know, as moderns, the arguments for science and provable fact. Therefore we should be ready at least to consider the proposition put before us: Do we choose science or religion, atheism or faith?

Karen Sue Smith, newsly retired, is the former editorial director of America.

Best Ignatian Songs: “Comfort, Comfort, O My People”

by Jim Manney

“Comfort, Comfort, O My People” is a lovely Advent hymn, based on verses from Isaiah 40. This version is by the Ignatian Schola, a Manhattan-based vocal ensemble composed of Jesuits and lay colleagues. Thanks to Michelle Francl-Donnay for the pointer. (Click here to watch the video on YouTube.)

The Jesuit China Mission: A Brief History, Part I (1552-1800)

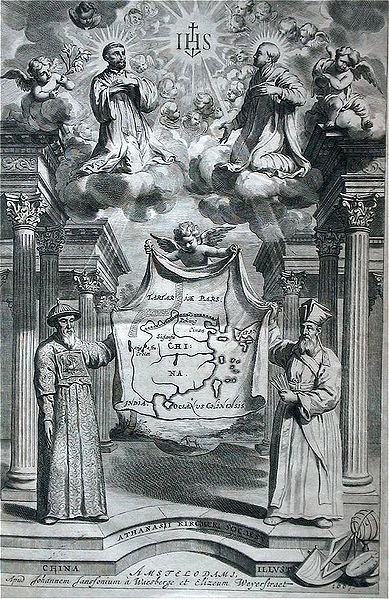

Above: Francis Xavier (left), Ignatius of Loyola (right) and Christ at the upper center. Below: Matteo Ricci (right) and Johann Adam Schall von Bell (left), all in dialogue towards the evangelization of China.

By Paul Mariani, S.J.

Fr. Paul Mariani is Assistant Professor of History at Santa Clara University. His book Church Militant: Bishop Kung and Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai has been recently published by Harvard University Press.

I. Introduction

Since its beginning, the Society of Jesus has had a close connection with China and the Chinese people. Perhaps no Catholic religious order has had such a strong relationship with a particular country as the Society of Jesus has had with China. This should not surprise us. St. Ignatius (1491-1556), founder of the Jesuits, himself wanted Jesuits to be available for worldwide mission. They were to be available for mission to the Turks and to “the region called the Indies” for “the defense and propagation of the faith.” In fact, the zeal with which these early Jesuit missionaries set out was one of the most impressive apostolic ventures in the history of the church. Some have even compared their efforts to a second apostolic era. And of the many places that the early Jesuits evangelized, they would soon prize China as one of their key missions.

In fact, the Jesuits were the third act in Chinese Christian history. The first Christian missionaries to what is today China had come as early as the 7th century. They were the so-called Nestorians, from the Church of the East. The second group was the Franciscans who came to China some 400 years later. They even built the first Catholic Church in Beijing in 1299. Neither of these early Christian communities survived. The third act would. For the Jesuits helped to found a vibrant indigenous church, and thus inaugurated modern Chinese Christian history.

The history of the Jesuit China mission is necessarily a vast subject. My purpose here, in this first of two articles, is simply to trace some of the key developments of the mission from its promising start in 1552, to its unfortunate decline and near destruction by 1800. Further, in order to help guide our path and focus our efforts, I will make use of several recent books, most of them published in the last ten years. Therefore, it is my hope that this essay may serve as a state of the field survey, in order to better acquaint the reader not only with the general contours of this fascinating history, but to highlight the contributions of the latest scholarship as well.

II. Francis Xavier and the Pioneers of the Early Jesuit Mission

It was none other than Francis Xavier (1506-1552), one of the original founders of Jesuits, whom Ignatius sent to be the first Jesuit apostle to “the Indies,” and this even before the Jesuits had received final approval for their new institute. After ten years of work in India, Indonesia, and Japan, Francis Xavier died on the small island of Shangchuan overlooking mainland China. In fact, over the years, St. Francis Xavier himself has come to symbolize some of the unbounded hopes and frustrated desires of the Jesuit China mission. For Francis Xavier never set foot in mainland China, but succeeding groups of Jesuit missionaries would attempt to fulfill his dream.

The story is familiar to many. After arriving in Japan in 1549-only six years after first European contact-Xavier soon learned that the Japanese looked to China as the source of culture, much like early modern Europeans looked to ancient Greece and Rome. Xavier was soon put on the defensive. If Christianity was such a great religion, why had the Chinese failed to mention it? To answer this objection, Xavier resolved to travel to China and even to the court in Beijing. His plan seems to have been first to evangelize China, and then resume his mission in Japan. Such a course of action might strike us today as being simplistic. Did Xavier really think he could accomplish this task so readily? His naïveté is apparent, but so is his zeal. For Xavier, no barrier was insurmountable-be it linguistic, cultural, or geographic-in the mission of evangelization. The following excerpt from a letter about China shows his boundless energy and aspirations: “Nothing leads me to suppose that there are Christians there. I hope to go there during this year, 1552, and penetrate even to the Emperor himself. China is that sort of kingdom, that if the seed of the Gospel is once sown, it may be propagated far and wide. And moreover, if the Chinese accept the Christian faith, the Japanese would give up the doctrines which the Chinese have taught them” (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1552xavier4.asp). It was precisely a letter such as this that would stir the zeal of generations of would-be missionaries.

Yet problems abounded, including the fact that China was closed to foreigners. Xavier tried to get himself named as a papal ambassador. The plan failed. Xavier then tried to get smuggled into China on a boat. This attempt also failed. The boat never showed up and Xavier died of exhaustion in Shangchuan, a small island just off the coast of mainland China.

Much of Xavier’s story is widely known. In fact, Franz Schurhammer wrote a four-volume biography of Xavier which has been translated into English. It is a painstaking and magisterial account of the life of the saint. Indeed, it is one of the most detailed biographies of all time. Another great source is the Letters and Instructions of Francis Xavier, translated by M. Joseph Costelloe and published by the Institute of Jesuit Sources.

In the thirty years after Xavier’s death some fifty missionaries-Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians-tried to gain entry into China. Some embarked from Macau (Macao), which had been made a Portuguese trading post in 1557. Others set out from the Philippines. Often enough, their goal was to reach Canton or even coastal Fujian Province. However, since China was still off limits for foreigners, they risked imprisonment. In fact, none of these missionaries were able to establish a permanent base inside China. The most they could hope for was to work for the release of European prisoners in Canton. Others did pastoral work mainly with European, often Portuguese, sailors and merchants in Macau. It was in Macau that the Jesuits established a permanent residence, as well as a school and a church. (In fact, to this day one can still see the façade of St. Paul’s Church.) But the establishment of a permanent Christian presence in China would need to wait.

III. Matteo Ricci and the Christian-Confucian Dialogue

In 1552, the same year that Francis Xavier died in Shangchuan, Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) was born in Macerata, Italy. To this day, in both East and West, he remains the best known Jesuit missionary to China.

Ricci arrived in China in 1583, guided by Michele Ruggieri (1543-1607), who had already made a successful entry into China. They had already secured permission to establish a residence in Zhaoqing, a small city upriver from the bustling port of Canton. It was from Zhaoqing that Ricci began his 18-year “ascent” to Beijing.

Ricci took his cues from and further refined the mission methods of Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606), who, in 1572, had been named the Visitor of the Jesuit missions in the East Indies. In this role, Valignano became the architect of a policy of missionary accommodation. In time, in China at least, this policy would come to mean that missionaries were to learn Chinese in order to dialog with the literati and to read the Chinese classics, to value China’s time-honored customs and culture, and to use Western science and technology as a method of attraction. The policy would also come to be associated with a top-down approach, whereby missionaries were to focus their efforts on the elite, in the hopes that this work would then trickle-down to the popular classes.

The story has been widely told. Ricci first wore the garb of Buddhist monks. Little did he know that Buddhism had been in decline for some time in China. He soon realized his mistake and recast himself as a Confucian scholar, a choice which would hopefully make him more credible with the leading officials. In this capacity, he set about mastering Chinese, which he did, even to the point of delving deeply into the Confucian classics, and being able to dialog with leading officials. With much help, he translated many western scientific works into Chinese.

Ricci’s own mission methodology is best exemplified in his most well-known book, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. Ricci structured this book as a dialogue between two scholars, one from the West and one from China. They both speak generally about questions of human existence. It is only at the end that the Western scholar mentions the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. Ricci knew that to begin with the passion accounts would offend Chinese sensibilities, especially among the literati. A crucified God would have shocked them. Ricci would only tell the Chinese about the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus after they had been adequately prepared.

What was Ricci like? Was this top-down approach correct? Was this his only approach? These debates occupy scholars today. They are also some of the issues that R. Po-Chia Hsia takes up in his 2010 work A Jesuit in the Forbidden City: Matteo Ricci, 1552-1610. Hsia is a deft guide, one who is uniquely capable of describing “the story of Matteo Ricci and his world.” Hsia is, by training, a historian of Early Modern Europe, a subject area on which he has written extensively. With this background, he is a natural fit to study Ricci. For Hsia has mastered not only the key European languages, but classical and modern Chinese as well. This allows him to probe the most important sources and archives relating to Ricci: the Fonti Ricciani by Pasquale D’Elia; the works of Pietro Tacchi-Venturi; the Jesuit China Archives in Rome; the 18-volume Documenta Indica, (1540-1597); and the official history of the Ming dynasty. Hsia is thus able to bring his considerable talents to bear on the subject of Matteo Ricci, a man who symbolizes the meeting point of East and West.

Hsia’s work is a delight to read not only for its breadth of knowledge, but also for the elegance of its prose. For example, describing Ricci’s world, Hsia says: “Born into a world torn asunder by the Protestant Reformation, he departed a Catholic Europe renewed in strength, restored in confidence, and restless in combat, against heretics and infidels, enemies of the Roman Church.” On Ricci’s project, Hsia writes in the prologue: “By his intelligence, charm, and endurance, the Italian missionary gained access into the inner realm of Chinese civilization, denied to almost all visitors. To use a metaphor of the Jesuits, he had hoped to enter the house and compel its residents to exit with him in allegiance to the Catholic faith.”

While Ricci and other Jesuits were set on increasing God’s glory in places like China, they, at times, overstated their case. Hsia is sensitive to this fact. For Ricci led some Chinese scholars to believe that one of the reasons for the success of Christianity was that Europe was without war for 1600 years! Hsia himself notes that he has recently become interested in things “Jesuitical.” Surely he knows this adjective has multiple meanings, not all of them complementary. I find this apt because, while he is respectful and even laudatory of Ricci, he is not above calling into question some of Ricci’s legacy. Perhaps Ricci was not above being “Jesuitical” himself.

In the book, Hsia traces Ricci’s life from his birth in Italy, to his entrance into the Jesuits and his studies at the Roman College, to his inspiration and perception of a missionary call, to his departure from Portugal and his arrival in Macau in 1582, and finally to his successful entrance into the mainland and his long journey to Beijing. It was in Beijing that he was able to work near the center of imperial power. Hsia also has a chapter on Ricci’s The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. His epilogue deals in greater depth with the historiography of Ricci scholarship.

In his text, Hsia explains why Ricci, even 400 years after his passing, remains a compelling figure today. In Hsia’s estimation, part of the reason is due to the good public relations of fellow Jesuits. After all, they propagated the “master missionary with the master narrative.” And Hsia notes: “There is something irresistible in this narrative: by virtue of his intellect, a heroic individual bridges impossible chasms between civilizations, opening up a new world of understanding by the strength of his learning and genius.” Indeed, this is a fitting coda to Ricci, widely known in the West, and one of a few foreign missionaries still held in the highest esteem in China today. In fact, Ricci was the first foreigner in China to be given an imperial burial. Even today one can visit his tombstone at the Zhalan cemetery on the western edge of old Beijing.

IV. The Generation of Giants: Jesuits at the Court and in the Provinces

Other illustrious Jesuits followed in Ricci’s footsteps. Ricci and these others have been immortalized by George Dunne as the “generation of giants.” In fact, the contributions of Ricci’s generation and after can be divided into two major groups. The first group was those who labored in the Beijing court or with other members of the elite. These Jesuits employed a top-down approach. They were convinced that even if the faith never made it outside of elite circles, they could still consider their mission a success. This is because, according to Hsia, “Ricci thought it better to have a small, high-quality Christian community than a large multitude.” The second group of Jesuits was more involved in direct pastoral work in the countryside. They employed a bottom-up approach by focusing on the popular classes at the grassroots level. All told, according to Hsia, the number of Jesuits who labored in both groups numbered some 500 Jesuits between Ricci’s death and the suppression of the Jesuit order in 1773.

Let us first take up the contributions of the court Jesuits. Many of them would eventually be buried with Ricci as a sign of imperial favor. These missionaries made it to China in the first place through the efforts of Nicolas Trigault (1577-1628). In fact, it was Trigault’s On the Christian Expedition in China-a work which relied heavily on Ricci’s letters-which publicized far and wide the work of the Jesuit China mission. The book was a major success, especially in Jesuit circles. With such deft use of publicity, Trigault was able to recruit capable Jesuits for the China mission. They, in turn, were followed by many others. Trigault himself made other contributions as well. He got permission to translate the Bible into literary Chinese and to use the Chinese language in Mass. (Permission was given for a mass in Chinese, but, by the time it was given, it was too late to put into effect.) In sum, according to Hsia, Trigault “propagated the Riccian legacy” and was “the spokesperson of the Jesuit China Mission.”

Let us briefly describe the contributions of some of these Jesuits, both those recruited directly by Trigault, and others as well. A wonderful resource for much of this history is the Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635-1800, edited by Nicolas Standaert, and published in 2001. This book, nearly 1,000 pages in length, although not inexpensive, is indispensable for the researcher interested in the early years of Christianity in China. One article alone, by Nicole Halsberghe and Keizô Hashimoto, discusses the work of the Jesuit astronomers in China. The earliest of these astronomers was Adam Schall von Bell (1592-1666). Having been recruited by Trigault, he left for China in 1618 along with 21 other Jesuits. So dedicated was he to his mission, that he brought with him an entire science library. He ultimately wrote many treatises for the emperor, and he became a first class mandarin and the President of the Mathematical Tribunal.

Schall also worked at the Bureau of Astronomy, which he directed from 1645 to 1664. As such, he was responsible for transferring much European astronomy to China. It was in this role that Schall and other Jesuits aroused antipathy within the court. It seemed clear why the foreign presence at the court was resented. For, as Halsberghe and Hashimoto note, the Jesuits “were in charge not only of the calendar, but also of the calculations and predictions needed to perform rites properly.” The performance of these rites was crucial in the smooth functioning of the government. But it offended some at the court that foreigners had such an important role in matters touching so closely on Confucian philosophy and matters of state. Thus, the Jesuits became embroiled in the famous “calendar case” when a certain Yang Guangxian brought the Jesuits to trial. They were accused of choosing an “inauspicious” date for the funeral of a prince (718). Schall was sentenced to death. In time, however, Yang’s own calendar was questioned, and Schall and the more accurate Western method of calendrical calculation were exonerated.

Ferdinand Verbiest (1623-1688) was then made Vice-Director of the Bureau of Astronomy. In this capacity, Verbiest is best known for continuing the work on the calendar and for building astronomical instruments that were used at the observatory. (Some of these instruments can still be seen in Beijing today.) Verbiest also revised astronomical compendiums, and he even helped to cast cannons for the Chinese government.

Ricci, Schall von Bell, and Verbiest, are among the most well-known, but a host of other Jesuits also had impressive accomplishments. For example, there is the striking story of Bento de Góis (1563-1607), a Jesuit brother, who traveled overland to China from the court of the Great Mogul Akbar in current-day Afghanistan. He thus followed in the footsteps of Marco Polo and showed that China was the same place that medieval Europeans called Cathay. Luigi Buglio (1606-1682) translated into Chinese important liturgical books such as the Roman Missal and the Roman Breviary. Martino Martini (1614-1661) published an atlas of China. Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was an influential court painter. (For further information on some of these Jesuits, see Thomas F. Ryan’s 2007 short popular account simply titled Jesuits in China. A helpful online resource is the New Advent website.)

Up to this point, as we have seen, most of these Jesuits were from Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Germany or Switzerland. They were all part of the Portuguese Vice-Province and worked under the protection of the Portuguese Padroado. This status quo was soon to change. For it was Verbiest himself who wrote a letter requesting more Jesuit astronomers. An article by Claudia von Collani in the Handbook explains that Louis XIV responded to this request and sent French Jesuits as the “King’s mathematicians.” Five of them reached China in 1687. Thus began the French Jesuit mission. By 1700 this mission had its own superior and plot of land, and was made independent from the Portuguese Vice-Province. The French mission still had to answer to the delegate of the Jesuit superior general. Yet efforts to bring the French mission under the Vice-Province failed.

The French Jesuits were highly successful. Many of them worked at the court: some were tutors to the emperor; some were engaged in astronomy; and some worked on cartography. Regarding cartography, von Collani further explains that they began this work in 1708 and finished ten years later. These Jesuits traveled throughout China and eventually produced an atlas of the realm, the result of which was that China was now “better mapped than Europe” (315). Interestingly enough, some French Jesuits went beyond missionary accommodation and tried to harmonize biblical accounts with ancient Chinese history. Some tried to show that “religion in ancient China and Christianity were in principle the same” (315). The more radical among them were called Figurists, because, as von Collani notes, they often used typological exegesis to discover-what they believed to be-intimations of Christianity in the Confucian classics. The hope was that Chinese Christians now had a way “of preserving their tradition without having to refer to Judea” (669). Some Figurists even believed that some Chinese characters had an originally religious meaning. For example, the character for heaven-it was conjectured-was a composite of the characters for a human being and the numeral two. It thus referred to the second person of the Trinity!

All told, these French Jesuits also acted as mediators between China and Europe. They not only brought western science and technology to China, but they propagated their impressions of China to a European audience as well. One of the best known of these French Jesuits was Antoine Gaubil (1689-1759) who was not only an astronomer, but a historian and a translator of Chinese books as well. Many of their impressions, including those of Gaubil, were sent back to Europe by way of letters which have come down to us as the Lettres édificantes et curieuses (Edifying and Curious Letters). They describe the Jesuit mission and the Chinese situation in great detail. (Some of these letters can even be found online at http://www.archive.org.)

Let us now turn to those Jesuits that worked in the provinces. The fact is that even during Ricci’s time, there were Jesuits laboring far from the court. In fact, the over-emphasis on Ricci is now being corrected by scholars such as Liam Brockey, who in his prize-winning book Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724, makes a strong case that: “An exaggerated emphasis on Ricci and his successors in Peking, a view that has long characterized histories of the mission, has almost completely overshadowed the work of…[other Jesuits]…who were busy propagating Christianity at the Jesuits’ other residences” (51).

It was precisely at the other residences that the Jesuits had more time to engage in direct evangelization. These efforts bore fruit. In the region around contemporary Shanghai, they were able to introduce the Marian Sodalities, and other such devotional groups, which were quite effective in recruiting local Christians, and channeling their energies on behalf of the church. Some of them were inaugurated as early as 1609, one year before Ricci’s death.

Brockey also gives the telling example of Giulio Aleni (1582-1649) who traveled to distant Shanxi Province, and then to coastal Fujian Province where he founded a mission. (The history of Aleni’s work in Fujian along with later developments under the Dominicans can be found in Eugenio Menegon’s excellent 2009 book Ancestor’s, Virgins and Friars: Christianity as a Local Religion in Late Imperial China.) Aleni is responsible for authoring dozens of books including: an illustrated life of Christ, a manual on how to make a good confession, a life of the saints, and a popular catechism for children. This latter work was based on the Four Character Classics, which were popular primers for elementary school students. It was inculturated Christianity at its best: Chinese in form, and Christian in content.

In sum, the Jesuit mission methodology was bearing great fruit. Yet, it was not without its detractors.

V. The Chinese Rites Controversy and the Decline of the Jesuit China Mission

The Jesuits’ accomodation to Chinese culture and their mission method were bearing fruit. Yet, when other missionaries, such as the Dominicans and Franciscans, came to China, they were not comfortable with some of the Jesuit accommodations. Thus began the Chinese Rites Controversy, which absorbed the energies of the Church for nearly one hundred years.

A concise guide through this extraordinarily complex and freighted history is still Francis Rouleau’s 1967 article in the New Catholic Encyclopedia. I will rely heavily upon his account. Rouleau calls this controversy “among the most momentous” in the history of Christianity. For the sake of simplicity, he divides his treatment into two important parts. First, he defines the Chinese rites. Second, he describes the controversy between the Jesuit position and the position that the Vatican would eventually take.

In defining the rites, Rouleau describes three related issues. First, there were the Confucian ceremonies that the scholar class periodically held in temples and halls dedicated to Confucius. This class was duty-bound to honor Confucius much like, in today’s world, a civil or military official will salute the flag or sing the national anthem.

Second, there was the “cult of the familial dead”, which “was manifested by the kowtow, incense burning, and serving food before the grave.”

Third, there was the “term question.” This revolved around the vocabulary the missionaries used to explain Christian concepts. For example, given the choice between introducing foreign words, or using Chinese words to describe God, the Jesuits chose the latter. This implied that the Confucian classics-where they found these terms-had a monotheistic view of God.

After mastering Chinese and reflecting deeply on the Confucian classics, Ricci made a decision in 1603 which argued that the rites in honor of Confucius were civil, not religious acts. Second, honoring the dead was “perhaps” not superstitious, and he permitted them. Therefore, these two specific rites could be isolated from what other Christians might call a “pagan” or “superstitious” environment. Finally, the Chinese terms Tian (heavens) and Shangdi (Lord above) were permissible to describe the Christian God. All told, Ricci felt that permitting these ceremonies was a necessary requirement for large-scale conversion. Since these rituals and terms were fully embedded in the Chinese social and cultural context, Chinese converts should be permitted to continue using them. They need not cease being Chinese by becoming Christians.

Others were not convinced. Already by 1631, Dominicans were arriving on the scene, and the Franciscans returned in 1639. Some of them felt that the Jesuits were permitting idolatrous practices. In 1643, a Dominican went to Rome with some questions. Thus began what has become known as the Chinese Rites controversy. The Vatican first argued for the Dominican position. Then a Jesuit went to Rome and clarified the situation. Pope Alexander VII accepted the Jesuit understanding in 1656. The rites “as explained” were then permitted for the next 50 years. In fact, during these years, Chinese emperors continued to be happy with the Jesuits and their work at the court. The high water mark was reached in 1692, when Emperor Kangxi granted the Edict of Toleration which permitted Christian missionaries to preach throughout China. Thus, the missionaries now had imperial blessing as well.

Yet, the controversy would not die down. In 1693, Charles Maigrot, the vicar apostolic of Fujian, once again called the rites into question, and, according to Rouleau, “the Holy See became involved in a judicial process of extraordinary complexity.” The Vatican now had to determine whether the rites were compatible with Christian doctrine. In doing so, it had to try to understand their role within the utterly foreign Chinese cultural context. Special church commissions were convoked from 1697 to 1704. Finally, in 1704, the Vatican reached a decision.

The key points of the 1704 decree were the following: It forbade the use of Tian and Shangdi for God. It also forbade ceremonies to honor Confucius and to honor ancestors. Even so, “a simplified commemorative name tablet” of the familial dead was permitted in Christian homes. This is what the decree did do. What it did not do was to determine whether the 1656 Jesuit explanation of the rites was true or misleading. Further, it made no statement as to the validity of the Confucian classics. This was beyond the competence of the Church authorities. The decree, then, simply stated that the rites were incompatible with Christianity. It made no further judgment on the validity of the Confucian philosophical system. Therefore, it argued against the Jesuit viewpoint that these practices could somehow be isolated or even purified from the “superstitious” Chinese cultural context. In other words, except for a few minor concessions, the rites would no longer be permitted.

As one might expect, this decision angered Emperor Kangxi, who had himself stated that these rites were civil in character. He took further umbrage that Europeans would dare explain to him the nature of Chinese practices. He then demanded that if the missionaries wanted to continue their work in China, they needed to obtain a certificate stating that they agreed with Ricci’s methods. Likewise, the Church also demanded its own oath of compliance. Thus, especially after 1707, mission work in China became especially precarious. The combined rulings of the emperor and the Vatican left missionaries in a bind. Should they obtain the certificate or sign the Church oath? Should they abandon China altogether? Should they stay on illegally? Should they stall for more time? A great irony in all of this is that these rulings were made when the missionary presence was larger than ever. For, at this time, the number of foreign missionaries, from all the orders that had congregations, had peaked at about 140.

Yet, for all of them, the situation became increasingly tenuous. The Vatican followed up with a further decree in 1715, and one in 1742 which definitely closed the controversy. In addition, in 1724, Kangxi’s son, Yongzheng, outlawed Christianity as a “perverse sect.”

Yet even under Yongzheng, some priests were permitted to stay on in Beijing. They put in long days of service at the court. They thus tried to create goodwill between themselves and the emperor. The hope was that this goodwill would take the pressure off those missionaries and Chinese priests that continued to labor in the countryside.

This was not the end. In a complex test of wills between the papacy and European governments, the Jesuit order itself was suppressed in 1773. The stream of Jesuit missionaries to China dried up. Further, those Jesuits that remained in China, both foreign and Chinese, now technically labored as diocesan priests. A notable example was Gottfried von Laimbeckhoven (1707-1787) who worked in the provinces. He ultimately became bishop of Nanjing and even administrator of the diocese of Beijing. However, for all intents and purposes, the Jesuit China mission collapsed.

These were also dark years for the Church as a whole. The Enlightenment had called into question faith itself; the French Revolution ushered in a period of Church persecution; and the Napoleonic wars caused chaos throughout Europe. In sum, the upheavals in Europe affected Catholic missions worldwide.

In the 250 year history of the “old” Society, the Jesuits had left their mark. They had served emperors, brought in key scientific information, dialogued with top officials, served at the Bureau of Astronomy, baptized Christians, and put the local church on a solid footing. When Jesuit efforts are combined with the work of others, both local and missionary, the sum result is impressive. For, even in the troubled late 18th century, the number of Catholics in China-by many accounts-surpassed 200,000.

Would these local Christians weather the storm? Would the Society of Jesus be restored? Would the Church itself revive and send out missionaries? We will explore these issues in the second part.

Why Do We Pray?

By William A. Barry, SJ

From God’s Passionate Desire

Why do we pray? Do we pray for utilitarian reasons-because it benefits our physical or psychological health?

Honesty compels me to say that I often do pray for utilitarian reasons. First of all, most of my prayers of petition ask for some good result, either for me or for someone else or for all people. Moreover, I feel contented when I remember in prayer the people who mean much to me, even if my prayer is not answered. I notice, too, that I feel better about myself when I pray regularly. I feel more centered, more in tune with the present, less anxious about the past or the future. So I suspect that I do pray for the purpose of psychological or physical health. But does that exhaust my motivations for prayer?

Prayer Is a Relationship

Thinking of prayer as a conscious relationship, or friendship, with God may be illuminating. Why do we spend time with good friends? As I pondered this question, I realized that I relish times with good friends for some of the same reasons just adduced for spending time in prayer. If I have not had good conversations with close friends for some time, I feel out of sorts, somewhat lonely, and ill at ease. When I am with good friends, I feel more whole and alive.

Still, I do not believe that my only reason for wanting time with them is to feel better. I want to be with them because I love them. I am genuinely interested in and concerned for them. The beneficial effect that being with them has on me is a happy by-product. Moreover, I have often spent time with friends when it cost me trouble and time, and I did it because they wanted my presence. Haven’t we all spent time with a close friend who was ill or depressed, even when the time was painful and difficult? Such time spent cannot be explained on utilitarian grounds. We spend that time because we love our friend for his or her own sake.

Of course, there are times when we need the presence of close friends because we are in pain or lonely. Friendship would not be a mutual affair if we were always the ones who gave and never were open to receive. But if we are not totally egocentric, we will have to admit that we do care for others for their own sakes, and not just for what we can get from the relationship. We spend time with our friends because of our mutual care and love. Can we say the same thing about our relationship with God?

Our Deepest Desires

Prayer is a conscious relationship with God. Just as we spend time with friends because we love them and care for them, we spend time in prayer because we love God and want to be with God. Created out of love, we are drawn by the desire for “we know not what,” for union with the ultimate Mystery, who alone will satisfy our deepest longing. That desire, we can say, is the Holy Spirit of God dwelling in our hearts, drawing us to the perfect fulfillment for which we were created-namely, community with the Trinity. That desire draws us toward a more and more intimate union with God.

We pray, then, at our deepest level, because we are drawn by the bonds of love. We pray because we love, and not just for utilitarian purposes. If prayer has beneficial effects-and I believe that it does-that is because prayer corresponds to our deepest reality. When we are in tune with God, we cannot help but experience deep well-being. Ignatius of Loyola spoke of consolation as a sign of a person’s being in tune with God’s intention. But in the final analysis, the lover does not spend time with the Beloved because of the consolation; the lover just wants to be with the Beloved.

Thanks and Praise

Another motive for prayer is the desire to praise and thank God because of his great kindness and mercy. In contemplating Jesus, we discover that God’s love is not only creative but also overwhelmingly self-sacrificing. Jesus loved us even as we nailed him to the cross.

If we allow the desire for “we know not what” to draw us more and more into a relationship of mutual love with God, then we will, I believe, gradually take as our own that wonderful prayer so dear to St. Francis Xavier that begins O Deus, ego amo te, nec amo te ut salves me: “O God, I love you, and not because I hope for heaven thereby.” Gerard Manley Hopkins translated the prayer:

I love thee, God, I love thee-

Not out of hope for heaven for me

Nor fearing not to love and be

In the everlasting burning.

Thou, my Jesus, after me

Didst reach thine arms out dying,

For my sake sufferedst nails and lance,

Mocked and marred countenance,

Sorrows passing number,

Sweat and care and cumber,

Yea and death, and this for me,

And thou couldst see me sinning:

Then I, why should not I love thee,

Jesu so much in love with me?

Not for heaven’s sake, not to be

Out of hell by loving thee;

Not for any gains I see;

But just the way that thou didst me

I do love and will love thee.

What must I love thee, Lord, for then?

For being my king and God. Amen.

Excerpt from God’s Passionate Desire by William A. Barry, SJ.

Stop. Look. Listen.

by Michelle

Earlier this week Paul Campbell at People for Others posted three short rules for maintaining our relationship with God. He wondered what rules other people might have. I hear “rule” and think “rule of life” – I’ve spent a long time praying with the Augustinians and I fear it shows. Years ago, the Augustinian who was my spiritual director encouraged me to write my own “rule of life.” A whole rule? I was too intimidated to try. Two decades later, I can sum up my rule of life and right relationship with God in three words: Stop. Look. Listen.

Stop. When I’m on the move, I have to watch where I’m going; so I don’t trip over anything, so I know when I’ve arrived. But all this focus on where I’m going too often reduces my vision to a tunnel. “Be still and know that I am God.” All around me.

Look. When I don’t have to watch where I’m going, I can notice what is around me. Stopping lets me see not only God before me, but God behind me, God beside me, God beneath my feet, God above me and – thankfully -God within me. (To take a page from St. Patrick.)

Listen. A friend who is a Sister of St. Joseph and a physicist once pointed out that sound is a touch, there is a direct physical connection between the source and the listener. Can I let God touch me? Can I allow the Word to touch my ears that I might hear; touch my lips, that I might speak His name in thanks and praise and petition; touch my heart that I might love; and touch my soul that my very being may grasp the image in which it was fashioned, the end for which I was created.

And I will admit that sometimes I get no further than “stop” before my to-do list starts snapping at my ankles. But I take heart in Abba Bessiaron’s wise advice from the 4th century. There is no need to cling. God is here, God is everywhere. Even when I’m not looking.

Funding shortfall leads to education gaps

A funding pitfall in education for the Burmese refugees along the Thai border may negatively affect their preparedness to go home.

The focus of the international donor community is shifting from the camps towards Burma, and a lack of sufficient resources has forced many organisations working in the camps, such as Jesuit Refugee Service, to make cutbacks to critical programmes like schooling.

“It will be difficult for young people [to return to Burma] if they don’t have an education”, said Lee Reh* a Karenni student who has lived in to the camp since 2001. JRS hopes that support for education can be bolstered so that the school programmes, and students, do not suffer.

Inside Burma, the Peace Donor Support Group, including the government of UK, Norway, Australia, EU, UN and World Bank, have offered a net total reaching nearly $500 million US to support peace building. Meanwhile, in the camps in Thailand, up to 25 per cent of funding for essential services may be cut, according to Burma Campaign UK (BCUK), a London-based advocacy and research organisation.

The refugee community fears that it may lead to higher student dropout rates, premature return and less preparation for a durable solution. JRS partners with the Karenni Education Department (KnED) to implement education programs in two Mae Hong Son camps where the majority of the refugee population hails from eastern Burma’s Kayah state. However, JRS has been unable to attain the full amount – roughly US $800,000, or 24 million baht – needed to maintain the programmes in 2012.

JRS will struggle to stretch resources to cover the programme until the end of the year. Reviewing the secondary curriculum and staff recruitment have been suspended.

“We feel sad because of budget cuts”, said Khu Oo Reh, a refugee education official. Other sectors affected by funding shortages include support for basic humanitarian needs, such as food provision. Rations have been cut down to only 1,640 kcal per day per person – 22 percent less than the recommended 2,100 kcal required to meet international standards, according to the World Food Programme.

The risks of return

An estimated 160,000 refugees remain in the camps, fearful that the decline in assistance will inevitably force them to return before the country is safe.

“The government is trying to show the world the image that the country is changing into a democracy. It’s not true. There are still murders and tortures, as well as rape cases, uncleared landmines and [other forms of] violence”, Sha Reh, another student, told JRS.

While a number of ceasefire agreements have been signed in the last year, based on past experiences, this is no guarantee of peace. In January 2012 the Karen National Union (KNU) signed an agreement with the Burma government but renewed fighting broke out in the east only a few days later.

Similarly, in the northern Shan State, the rebel group, the Shan State Army was fired upon little over a week after signing a peace agreement at the end of January. The Burma military also refused to withdraw troops from agreed upon areas, according to local news sources. In addition, eastern and western areas are rife with landmines. Roughly five million people in ten out of Burma’s 14 states and regions are exposed to landmine contamination, according to Geneva Call, an international mine ban advocacy organisation. This poses serious challenges for repatriation.

“If repatriation does happen, the government will have to be ready to provide for people’s welfare, such as housing, security, education, food, healthcare and safety assurance”, Sha Reh added.

Education as preparation

JRS education programmes in Mae Hong Son and Khun Yuam districts, ongoing since 1997, aim to prepare refugees for durable solutions. JRS provides basic education, teacher training, special education, school materials, vocational training and non-formal education to 5,200 students in Ban Mai Nai Soi and Ban Mae Surin from primary to secondary school.

“Education is very important for our people. We need many skills because we’re poor. Many people are illiterate”, said Than Maung, a refugee teacher. JRS education and vocational training provide refugees with skills that will enable them to find good jobs later on, according to Than Maung.

Similarly, in May, Aung San Suu Kyi spoke at the World Economic Forum in Bangkok and emphasised the importance of education that would allow young people to reach their potential.

“What I’m afraid of is not so much joblessness as hopelessness”, she said.

In the camps, where people are trapped without freedom of movement, education provides hope for the future. Cutting back on assistance may push refugees back to Burma despite ongoing fighting and the risk of landmine contamination.

“Education is really important for the students”, said Khu Oo Reh.

Without the legal right to leave the camps to find other schools or jobs, the funding shortages leave the refugees to face a difficult path ahead.

“If there is no support for education, where will the students go to school?”, Naw Kreh, a refugee education official asked. Refugees cannot adequately prepare for return if funding for education dries up, according to the Karenni refugee students.