by Jake Martin, S.J.

Momentum often trumps skill come Oscar time. Industry buzz plays as much a factor in deciding whose white knuckles clench the golden trophy in March as the quality of a performance. A savvy media campaign is just as important as acting chops in nabbing the highest prize in Hollywood, and the focus on sizzle over steak has often left film lovers scratching their heads when “the Oscar goes to…” yet another unworthy recipient. This year things may be different.

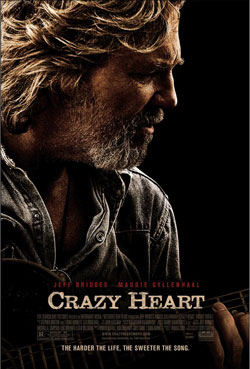

Jeff Bridges’ performance as a country crooner looking up from the bottom of a whiskey bottle in “Crazy Heart” is the perfect marriage of media hype and craftsmanship. Such is the weight of Bridges’ performance and the buzz surrounding it that the folks at Fox Searchlight saved it from the direct- to-DVD purgatory for which it was originally intended and give it a limited theatrical release. The producers must have been fairly certain that Bridges would get a nod from the Academy.

“Crazy Heart,” directed by Scott Cooper, is an unassuming, yet fully realized story of addiction and redemption. The narrative is direct and transparent; transitions are telegraphed from a mile away and nuance and deft sleight of hand are nowhere to be found. Yet this lack of subtlety in no way hinders the film’s agenda or makes its impact any less effective.

The film contains all the elements of a clichéd country ballad, complete with a dipsomaniacal protagonist, Bad Blake (Bridges), staggering through an endless series of one-night stands at half-empty honky-tonks. Perhaps the only thing surprising about “Crazy Heart” is its conclusion. It would seem almost an inevitability that a contemporary drama about a country-music singer would end in emptiness and despair. But Cooper, a first time director, who also adapted Thomas Cobb’s novel into the screenplay, seems utterly unconcerned with providing an existential chasm into which his hero can plummet. Indeed, he is more focused on advancing the remarkable story of an unremarkable man to allow trendy nihilistic undertones and hip narrative devices to interfere with the task at hand.

Historically, Hollywood’s portrayal of alcoholics has been, if not, entirely unrealistic, at least simplistically over the top. As anyone who has engaged with an alcoholic for any significant period knows, infrequently do their lives play out at the operatic levels of the celluloid drunks essayed in “The Days of Wine and Roses” and “The Lost Weekend.” More often, they are like Bad Blake, a man who manages to function just enough to get by, day by day, for years at a time.

The repercussions of addiction, while no less tragic, are often less dramatic than the standard didactic Hollywood offerings. The paint-by-numbers trajectory of alcoholism, which the film industry favors, often leads its audience to feel safely detached and immune from a disease that is far more subtle and destructive than the drunk-in-the-gutter portrayal that film industry has traditionally put forth. Not every alcoholic is like Nicolas Cage in “Leaving Las Vegas.” Some, like Bad Blake, manage to muddle through life in semi-coherent haze, and the tragedy is found, not in one moment of destructive excess, but rather in a lifetime of disintegration, as relationships, health and quality of life slowly but surely become compromised to the point of paralysis. The creative team behind “Crazy Heart” understands the complexities inherent in addiction and Bridges’ Blake, with his stubborn, almost blissful refusal to acknowledge his disease, makes for truthful and resonant movie watching.

Ultimately, it is all about Bridges, and he does not disappoint. The quintessential journeyman actor, if there can be such a thing in Hollywood, Bridges has gracefully moved through the better part of four decades giving one adroit, understated performance after another. Long overshadowed by peers with flashier styles and edgier personas, Bridges has always stood just outside the realm of the superstardom that seemed his right when audiences first beheld him in “The Last Picture Show.”

Bridges inherently unassuming and optimistic manner serves him well in the role of Blake, who, in less skilled hands would easily turn into a Saturday Night Live character gone bad. Instead, he manages to makes every move look natural. Bridges is the Spencer Tracy of his generation: never once are we aware that he is “acting,” and moreover, never does his performance get in the way of the story. The actor understands that at the root of all addictions is a myopic self-centeredness that impairs its victims to such a degree that even the simplest awareness of things outside the self are hard to come by. Yet because of his innate likeability we are never put off by his fundamental lack of cognizance.

Maggie Gyllenhaal, as the love interest, seems a bit too strident and impenetrable to be believable as a woman who would succumb to Bridges’ charms. While Bridges’ seems as if he was born with a bottle of Wild Turkey in his mouth, Gyllenhaal never manages to fully shed her actress persona, and she seems out of place in her Southwestern surroundings, as if waiting for the next bus out of Santa Fe and back to the familiar environs of Manhattan.

“Crazy Heart” bears more than a passing resemblance to “The Wrestler,” last year’s Oscar nominee, which resuscitated the career of Mickey Rourke. Unlike Rourke, however, Bridges does not need a comeback. He never went away. Rather, he’s been invisible, silently honing his craft year after year amidst a culture that seems only to affirm the damaging behavior of the kind Bad Blake and Rourke specialize. Yet that may change, if only for a brief few months, this Oscar season if Bridges finally receives the acclaim he so richly deserves. And it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.

Jake Martin, S.J., is a Jesuit scholastic teaching theology and theater at Loyola Academy in Wilmette, Illinois.

On the day that the six Jesuits, together with the community cook and her daughter, were murdered in El Salvador, I was at Cha Choeng Sau outside Bangkok. The Jesuit Refugee Service was holding a meeting, where we had heard from JRS workers of the suffering and resilience of refugees around Asia. We looked forward to hearing from Fr Jon Sobrino, the Salvadoran Jesuit theologian, who had been speaking at another meeting in Bangkok. But at breakfast we heard the dreadful news.

On the day that the six Jesuits, together with the community cook and her daughter, were murdered in El Salvador, I was at Cha Choeng Sau outside Bangkok. The Jesuit Refugee Service was holding a meeting, where we had heard from JRS workers of the suffering and resilience of refugees around Asia. We looked forward to hearing from Fr Jon Sobrino, the Salvadoran Jesuit theologian, who had been speaking at another meeting in Bangkok. But at breakfast we heard the dreadful news. It was in the campesino communities that I began to understand the six Jesuits and the theology evolving in El Salvador and other parts of Latin America. The figures of Julia Elba and Cecilia Marisela Ramos, the community cook and her daughter, then came into sharp focus. With that came some understanding.

It was in the campesino communities that I began to understand the six Jesuits and the theology evolving in El Salvador and other parts of Latin America. The figures of Julia Elba and Cecilia Marisela Ramos, the community cook and her daughter, then came into sharp focus. With that came some understanding.