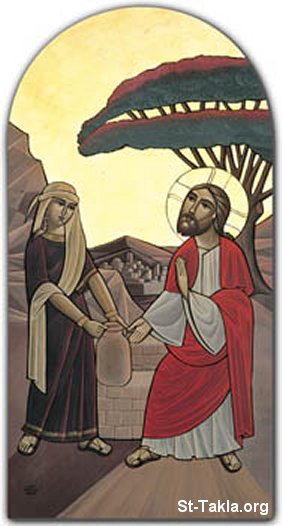

The easiest part, even if quite profound, is to see that Jesus shows up in out of the way places, without fanfare. He is in Samaria, among the Samaritans, near-neighbors of the Jews who believe that they were the ones who kept the faith after the Exile. Jesus is far from Jerusalem, yet not on the Samaritan holy mountain either: as is often the case, he is in-between, on the edge. He is by Jacob’s well, a site with long and holy memories, and to be sure, he comes to offer the water of life that everyone yearns for. But he does not ignore the well; he himself needs the water that if has been offering since the time of Jacob and Joseph. We can get quite far in interreligious affairs if we just take his words seriously: “But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him.” (4.23)

More difficult, though, is how to interpret the people who are in the story with Jesus: the disciples, the woman, and the people of the town.

Easiest to account for are his disciples: well-meaning, they go looking for food, and miss his dialogue with the woman; upon their return, they are surprised that he would be seen talking to a woman, and alone at that; they do not understand his words, that his true bread is to do the will of his Father. (4.34) They are not even mentioned at the end of the account. They seem to gain no insight, even if years later it will all begin to make sense. It is easy then to see in the disciples ourselves, especially those of us who are religious, priests, leaders in the Church: right at the heart of things, there all the time, and yet too often clueless, grasping for physical bread and missing spiritual meanings; busy spectators at the drama of salvation, missing the important part and not having a clue how to preach the word that is Christ.

And then there is the unforgettable figure of the woman, interesting in the raw singularity of who she is: A lone woman out by the well in the heat of midday; cowed into assuming that men will not speak with her, even accept water from her; assuming that Jews will want to criticize her Samaritan religion, looking down on it; burdened, as we learn, with a series of bad relationships, five husbands and more. Yet she does not run away: she stands up straight, talks to the stranger, argues a few points of theology, admits her own neediness. In the end, she goes off to the town, and without shame speaks to everyone: “Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah, can he?” (4.29) Surely she offers a fine lesson on how to preach the Good News: Confession: I myself have been challenged, my life before my eyes; I simply share what has happened to me. A real question: Could this be the one we seek? It is not a rhetorical question; she is not simply belaboring a safe theological lesson for her audience, the ending already in place. She is asking: Is this person I just met, the one we’ve always been seeking? What do you think? An invitation: Come and see. Don’t just listen to me, as if I am authorized to tell you all you need to know about the Christ. Go to him yourself, he is nearby. This woman was a better apostle than those who spent all their time with Jesus.

And finally, the people of the town. With a graciousness rarely seen in the Gospels, after meeting Jesus, these Samaritans beg him to stay with them, and so he does for two days. They listen to what he says, and with a clarity that even the woman does not display, they see who he is. As they say to the woman, “It is no longer because of what you said that we believe, for we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this is truly the Savior of the world.” (4.43) She has not stood in their way, and they have benefited from allowing Jesus to come into their ordinary, Samaritan homes. They do not become Jews; do they become disciples? Yes, in their faith, but of course there is no record of how their lives changed after this encounter. We can presume that they worshiped on that same Samaritan mountain — yet now “in spirit and in truth.”

John 4 is not simply a lesson on Samaritan religion, nor even the evangelist’s larger version of the parable of the Good Samaritan told in Luke. Yet we would have to be blind and deaf if we did not realize that Jesus found in the woman someone he could talk to, sharing who he is, that in the townspeople, he found people quite capable of hearing his message and taking it to heart in a most profound sense. And he was among people not of his own religion.

The outsiders are able to hear; those whose religion is suspect, recognize and welcome Jesus; Jesus shows up in the most unexpected, unusual places. If we just take these points to heart, we will surely be more ready to see Christ at work “outside the Church,” and do a better job inside it too.

So it is our motivation, good or bad, that determines the fruit of our actions.