2nd Week of Easter

3rd Week of Easter

4th Week of Easter

5th Week of Easter

6th Week of Easter

2nd Week of Easter

3rd Week of Easter

4th Week of Easter

5th Week of Easter

6th Week of Easter

The ceremony for the beatification of John Paul II, on May 1, 2011, presents a good discussion opportunity with children. Take, for example, the pontif’s view of God in our everyday life. People tend to segment their lives into two parts — the non-secular, spiritual part; and the secular part. More often than not, it’s the secular part that gets the most attention in the news, in the media and throughout our culture. John Paul II said that there cannot be two parallel lives. Every area of our lives enters into the plan of God, who desires that these areas be the places where the love of Christ is revealed and realized for both the glory of the Father and service of others.

Consider discussing these questions:

How was the love of Christ revealed to Pope John Paul II when he was a young child?

How would you find God if you had lived at the same time as John Paul II?

What aspects of John Paul II’s life would you like to emulate?

by David Scott

For forty days Jesus stayed among the people, until he was taken up to heaven in a cloud.

During this time, he laid the foundations for his church to continue his presence and work on earth.He gave final instructions to his twelve handpicked apostles, the patriarchs of this new extended family of God.

He had instructed them privately throughout his ministry and given them powers to heal and cast out demons in his name. In those last forty days, he taught them how to interpret the Scriptures and preach. He breathed his Spirit into them, confirmed their authority to forgive sins in his name. He gave them a mission-to preach the good news of his salvation to the ends of the earth, to celebrate the breaking of the bread in his memory, to teach what he had taught them, to baptize all nations and make them one family in God. He promised he would remain on earth through his church-present in the sacraments, living signs that truly bring people into contact with his saving presence.

Jesus ascended to heaven in his glorified, risen body. He took his place in heaven in all the fullness of his humanity, bearing for all time the marks where the nails had been, the signs of his passion carved forever into his precious skin. From that day forward, we could never think of God without thinking of humankind. The very being of God-the Trinity of Father, Son, and Spirit-now contains One who is one of us.

Jesus is now “seated in glory at the right hand of the Father.” He is “King of kings and Lord of lords.” He will come again one day to render a final judgment on the living and the dead and to usher in the never-ending kingdom that Israel’s prophets proclaimed, the new Jerusalem that will come down from heaven. Until that day, Jesus will remain our high priest in the precincts of heaven, hearing our prayers and sending us his Spirit. He is the one mediator between our Father and us, the only one who can save us from the sin of the world.

Until Christ comes again, Catholics live as the first apostles did-as witnesses to his resurrection, trying by his grace to testify with our entire being to the salvation he won for us. We live by faith in all that he revealed about God. We experience our lives as people born of the water and blood that flows from his sacred heart. We call God our Father and love all men and women as our brothers and sisters. We live by hope in the promise that the kingdom is coming, growing and spreading under the Father’s watchful eye in the church of his Son, empowered by his Spirit. And we live by love, in imitation of Jesus, with the love of God in our hearts giving meaning to everything we do. By his grace, we live as he did, as living “Eucharists,” as offerings of praise and thanksgiving.

And we see miracles every day, not only at the altar where bread and wine become his body and blood. We see lives changed by the encounter with the risen Jesus, and we believe that no person stands beyond the pale of his love. We have seen with our own eyes the truth of what he said, that with God all things are possible.

from The Catholic Passion: Rediscovering the Power and Beauty of the Faith by David Scott

© 2005 Loyola Press

My view of priesthood came from a wide variety of sources: Bing Crosby in “Going My Way,” Spenser Tracy in “Boy’s Town” and Pat O’Brien in “Angels with Dirty Faces” gave me images of wise but friendly, urbane yet sincere, demigods. From literature, I took on board Bernanos’ sickly young cleric from “The Diary of a Country Priest” and the unnamed “whiskey priest” from Graham Greene’s “The Power and the Glory.” These characters all seemed far removed from the awkward, humble and often inarticulate men I met at school and in my parish.

I was not a “pious” youth, so when I first found myself considering the notion of a vocation to the priesthood, I didn’t quite know where to turn. Happily, I found myself in the company of Thomas Merton and his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. His path, the experiences that led him to become a Trappist monk and priest, were vastly different from my own, and yet I could identify with the spiritual journey he recounted. Over the years, I have learned that Merton’s story has had a profound effect on many others discerning a vocation to the priesthood.

I decided to contact a friend of my sister, Fr. Peter Knott, S.J, who was the Catholic chaplain at London’s Heathrow Airport. I was attracted in equal measure by his straightforward holiness and boundless good humor. If I was going to be a priest, I wanted to be like him.

Peter counseled me gently and without pressure. He arranged for the Irish Jesuits to send me some literature. One pamphlet was a collection of articles that had appeared in The Irish Times, and it included some pretty strong criticism of the Jesuits, including some from former Jesuits. I thought to myself, the Jesuits have to be pretty cool if they are prepared to present potential recruits with such an unfiltered view of themselves.

My Jesuit journey has brought me from Dublin to Paris to Tokyo to Syracuse, NY, to Los Angeles and now to Chicago. Not every day (or year!) has been easy, but I am grateful for every single one of them. Priesthood has been an incredible blessing – I feel like I won the lottery!

Don’t miss Paul’s blog:

People for Others explores how working together to find God in everything helps people appreciate just how active God is in their lives.

Honoring Daniel and Sidney Callahan

The editors of America are pleased to honor Daniel Callahan and Sidney de Shazo Callahan with the Matteo Ricci, S.J., Award for their distinguished contribution to culture. They have contributed to the world of ideas, to letters, bioethics, moral philosophy and theology, psychology, spirituality and journalism. For a half-century they have lived a creative partnership rich in ideas and in values. Through their writing, research and lectures, they have taught both church and society how to think deeply about public problems, to explore our humanity and cultivate its deepest gifts in a potentially disorienting time of technological change. They have gathered round them in conversation circles of scholars and friends who with them cultivate the high form of friendship in which ideas and values are exchanged for the sake of the common good.

Their gift for civic friendship is one they share with Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), the Italian Jesuit polymath after whom this award is named. His most famous essay, “On Friendship,” is still regarded today as a classic of Chinese culture. Ricci and his companions bridged European and Chinese culture in a way no one has since. They shared with China the advances of Western science. They taught astronomy to mandarins, and Ricci himself designed an enormous map of the world that recorded the most recent geographic knowledge of the day. They also employed painting and music to communicate the Gospel to their friends. At the same time, they explained China’s Confucian culture to Christian Europeans, helping both to find commonality in difference. Ricci, his companions and successors were pioneers of a global culture.

In creating this award, the editors have been mindful of the standard Ricci set for multi-disciplinary learning with broad cultural influence. Daniel and Sidney Callahan have demonstrated equal breadth of learning and a passion for stirring dialogue over the issues of the day. The passions of their minds have inspired men and women to undertake research, join conversations and build communities of ideas where the future of our society and of our world continue to be debated. For the ways in which they have made the world of the mind live in the global public square, we are most pleased to present the 2011 Ricci Award for contributions to world culture to Daniel and Sidney Callahan.

America House, April 7, 2011

Here we offer a selection of Daniel and Sidney’s writings for America:

“Sullivan’s Travels,” November 9, 2009 “Happiness Examined,” February 23, 2009 “Limbo, Infants and the Afterlife,” April 3, 2006

Sidney Callahan

“Mary and the Challenges of the Feminist Movement,” December 18-25, 1993

“Counseling Abortion Alternatives: Can It Be Value-Free?” August 31-September 7, 1991 “Association for the Rights of Catholics in the Church,” July 26, 1986 “The Pastoral on Women: What Should the Bishops Say?” May 18, 1985 “Curbing Medical Costs,” March 10, 2008 “Curing, Caring and Coping,” January 30, 2006 “Paging the Unbandaged,” September 12, 1970 “Hooked on Ultimacy,” March 26, 1966 “Nobody Here But Us Pluralists,” December 7, 1963Daniel Callahan

Books for budding environmentalists

In the Book of Genesis, God creates a lush world thick with birds, fish, animals and every good thing, and entrusts this sacred gift to man. This environmental stewardship motivates “green” Pope Benedict’s activism, from installing solar panels in the Vatican to urging a response to global climate change. It is our religious obligation to protect the planet. St. Francis and the Animals, with gentle rhymes by Alice Joyce Davidson and accessible art by Maggie Swanson (Regina Press, 2006), provides a lovely introduction for young children to the Franciscan call to creation-care.

A host of books for young readers explore green themes. A new children’s picture book, richly illustrated by Jim Arnosky, offers a revision of this Genesis moment in all its primeval, Garden-of-Eden grandeur. In Man Gave Names to All the Animals (Sterling Publishing, 2010, ages 1-6 years), Arnosky illustrates the lyrics to “Man Gave Names to All the Animals,” by the Pulitzer Prize-winning songwriter Bob Dylan. You do not have to be a Dylan fan to appreciate Arnosky’s realistic pencil and acrylic paintings of 170 animals (all named on the back page) and the subtle message they send of our responsibilities as stewards of creation. If you are a Dylan fan, however, you will appreciate that the book comes with a CD of the song, a great way to turn story time into a sing-along.

A Classic

Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax (Random House, ages 4-8) also opens with echoes of Eden. But the primeval forest as imagined by Dr. Seuss (a k a Theodore Geisel) is composed of Truffala trees, rendered in eye-popping colors and improbable shapes. The Lorax is Seuss’s 20th-century adaptation of the Fall in Genesis. In Geisel’s version, mankind destroys paradise not by eating forbidden fruit but by chopping down all the fruit trees, a severe violation of Judaic law, bal tashchit.

Marking its 40th anniversary this year, the children’s classic is (unfortunately) just as topical today. The original tree-hugger, the Lorax, and his fantastic Seussian companions, the Brown Bar-ba-loots, the Swomee-swans and the Humming-fish, live in a “glorious,” balanced eco-system until the arrival of the Once-ler, who is “crazy with greed.” The Once-ler chops down the Truffala trees to make Thneeds, a consumer product of marginal utility; but, as the Once-ler crows, “You never can tell what some people will buy.” The Lorax argues for environmental protection and for the prophetic responsibility to speak on behalf of the voiceless. “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues. And I’m asking you, sir, at the top of my lungs” to stop the eco-genocide.

The Once-ler, intent on profit, retorts that “business is business! And business must grow!… I have my rights, sir, and I’m telling you, I intend to go on doing just what I do!” He does not heed the Lorax’s dire warnings, or even believe them, until it is too late.

As the tragedy unfolds, Seuss’s color palette fades from bold colors to grimy tones until Eden has been destroyed. But Dr. Seuss places his hopes in our children, giving them the last Truffala seed, and a mission; “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.” That is a wonderful line that I use in my classes at Catholic University. It will soon come to life in the 3D movie now in production, starring Mr. DeVito as the voice of the Lorax, Zac Efron as the boy given the last Truffala seed (named Ted in honor of Theodore Geisel) and with some new characters added, like Betty White as the boy’s grandmother. It speaks to our climate-changed, post-BP oil spill world. As Danny DeVito noted in an interview in USA Today, “We’ve got to wake up and smell the oil burning.”

Kevin Henkes, a Caldecott Medal-winning children’s book artist and author, playfully conveys the joys of nature and tending the earth in My Garden (Greenwillow Books, 2010, ages 4-8). In a perfect match of simple, poetic text and navy outlines with bright Easter egg colors, Henkes does not preach, but invites children to ponder the creative bounty of the earth. A young girl considers the wonders of her garden. “In my garden, there would be birds and butterflies by the hundreds, so that the air was humming with wings,” and “a great big jellybean bush.” Henkes plants seeds of the love of creation-care, covers them with dirt and pats “down the dirt with my foot…. Who knows what might happen?”

Gardens and Animals

In Let’s Save the Animals (Candlewick Press, 2010, ages 3-8), Frances Barry uses textured, cut-paper collages and ingenious layouts (the open book creates an oval shape, so readers hold the world in their hands) to urge her young readers to save the endangered species illustrated throughout the book. In large text she simply describes the animals in their habitats: “I’d save the orangutan, stretching from branch to branch and swinging through the tropical rain forest.” In smaller text creatively intertwined with the art, she offers more details about the causes of the animals’ demise. The lift-the-flap format not only invites reader participation but also underscores the book’s theme of these species’ precarious fate: “Now you see them, now you don’t.” Black animal cutouts against black backgrounds illustrate their absence. The final page spread lists 10 simple ways children can help protect endangered species.

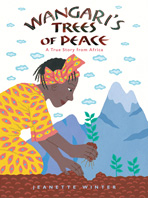

A non-fiction picture book by Jeanette Winter, Wangari’s Trees of Peace: A True Story from Africa, (Harcourt, 2008, ages 4-8), tells the inspiring story of Wangari Maathai, awarded the Nobel Prize for her Green Belt Movement. To combat deforestation in her native Kenya, she enlists local women to plant more indigenous trees. Trees help the land and the farmers avoid desertification and poverty, and they also build peace, as environmental degradation spurs violent conflicts over scarce farmland and resources. Her movement has spread to 30 African countries, helping poor, African women farmers, the poorest farmers on the earth (according to the U.N. World Food Program). Simple text and pictures clarify the intersections of environmental damage, poverty and violence. Imprisoned for her activism, Wangari is not the only to have been imprisoned. “Talk of the trees spreads over all of Africa, like ripples in Lake Victoria…until there are over 30 million trees where there were none.” Winter’s words are complemented by her bright colors and repetitive patterns that conjure up the beauty of Africa.

Now to Florida

The world is funnier with Carl Hiassen in it. A persistent and ironic investigative reporter, Hiassen has been writing exposés about corruption in South Florida for The Miami Herald for nearly 40 years. He weaves his stories with an honest, satiric wit reminiscent of Mark Twain. Recently, he has adapted his talent to middle school and teen fiction, with great success. In a trio of novels, kids become “everyday environmentalists,” sometimes reluctantly. They do not set out to save Florida’s wetlands and endangered species, but a funny thing happens on the way to school. They uncover corporate pollution and coverups and decide they must respond, while the adults around them are often either unable or unwilling to take on the issues. The quirky characters and deadpan descriptions of the good, the bad and the crazy in South Florida are as thick as Spanish moss in a Florida swamp, so real you will practically feel the mosquitoes bite.

In Hiassen’s Scat (Knopf, 2009, ages 9-12), a class field trip to the Black Vine Swamp goes unexpectedly awry, as their feared battle-axe of a biology teacher (the aptly named Mrs. Starch) and the class underachiever and arsonist, Smoke, go missing in a suspicious fire at the swamp. An oil company illegally drilling in the swamp set the fire in an attempt to cover their tracks and frames Smoke for the fire. But the persistence and ingenuity of the classmates Nick and Marta exonerate Smoke, find Mrs. Starch (actually an environmental activist) and save an endangered Florida black panther and her cub along the way. The pace, characters, sense of place and poignant humor of the novels alone make them essential reading. The green themes are a bonus. The author’s tongue-in-cheek humor and sunny Florida settings nicely balance the more serious ethical and environmental challenges. Readers familiar with Hiassen’s profanity-laced crime novels for adults can rest easy; these books are profanity-free.

It’s Easy Being Green

Because the specifics of creation-care can be complicated, a host of new non-fiction books clarify these issues for elementary-school age through teenage children and their parents and teachers. Three in this category stand out. What’s the Point of Being Green?, by Jacqui Bailey (Barron’s, 2010, ages 9-12), clearly explains environmental issues without talking down to children. Organized in useful blocks from “What’s the Problem?” and “How Did It Get So Bad?” to “So What Can We Do?”-suggestions for action at the individual, community and international levels-the book deftly weaves photos, facts and tips for action. The sections “Why Do Some People Go Hungry?” and “How Wealthy Are You?” are by themselves worth the price of the book, as many green books do not mention that the poor suffer most from environmental damage.

Earth in the Hot Seat: Bulletins from a Warming World, by Marfe Ferguson Delano (National Geo-graphic Society, 2009, ages 9-12), combines superb National Geogra-phic photography and compelling comments from scientists, like: “Things that normally happen in geologic time are happening during the span of a human lifetime. It’s like watching the Statue of Liberty melt.” The photos memorably tell the story, including before-and-after pictures of melting glaciers and representations of the carbon emitted by a sport utility vehicle.

A Kid’s Guide to Global Warming: How It Affects You and What You Can Do About It, by Glenn Murphy (Weldon Owen, 2008), also clearly explains climate change with fascinating pictures and graphs; but except for a photo in the disease section, the book overlooks the disproportionate effect of climate change on the world’s poor.

All these books shine a bright light on environmental pain, while urging individual and collective action to resurrect our suffering planet-a fine message for Earth Day and every day.

Maryann Cusimano Love, a professor of international relations at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., has written several children’s books.

Antonello da Messina and the suffering Christ

|

The head and upper chest of the figure emerging from the dark background seem at first to face us squarely. With its broad peasant’s nose and slightly parted, full lips, the face would not be remarkable but for the searching eyes and their haunting expression. Gradually one notices, thanks to the light and subtle modulation of the flesh, that the head and shoulders turn somewhat to their left. Resting lightly on the figure’s head, and casting a shadow, is the strangely delicate circlet of a thorny branch. (Were it gold, it could almost be a prince’s crown.) The arms are bound behind the figur’s back.

This is Antonello da Messina’s “Christ Crowned With Thorns” (see cover), a painting from 1470, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and an exquisite example of what has been called an Ecce Homo or Man of Sorrows genre that had been popular in the West for almost two centuries before this panel was painted. (In the East the theme emerged in the 12th century.) This suffering Christ confronts not just his tormentors but everyone who is arrested by his image. He suffers, yes. Above all, though, he questions. What might he be saying? Subject to such abuse, does he defend himself? Implore? Accuse? Judge, perhaps?

One remembers the Reproaches of the Good Friday liturgy: “My people, what have I done to you? How have I offended you? Answer me!” Except that this face is as gentle as it is searching; this wounded body is still somehow inviolate. Only the first verse of the Reproaches seems to apply: “My people, what have I done to you?”

The Christ this painting invites us to contemplate is too infinitely open to be demanding. “Why?” he simply asks. Why are you doing this? Rather than judge or accuse, his eyes-which seem to follow you wherever you go in the gallery-see into all unwarranted human suffering, raising the question of its meaning in the simplest, most elemental form. We wish the lips would part farther, to utter a word to which we could respond. For the mute, hurt gaze allows no self-justifying response, nor even a plea for forgiveness. It is life itself that is questioned: our human nature and the God who created it.

The French philosopher Jacques Maritain once spoke of poetry as “that intercommunication between the inner being of things and the inner being of the human Self which is a kind of divination…what Plato called mousiké.” In this sense one might well call the author of this work, Antonello da Messina, a poet and a poetic master of contemplation.

Antonello’s Story

The artist was born Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio about 1430 (the details of his biography are unclear) in Messina, at that time part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. After an apprenticeship he traveled to Naples, where sometime between 1445 and 1455 he became a pupil of Niccolò Colantonio and learned the techniques of Flemish oil painting. It was a time when Spanish, Provençal, Flemish and Italian influences all mingled in Naples. Antonello also was exposed to the great Netherlandish art that the king patronized, probably including works by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden.

By 1457 or so, Antonello had married in Messina, had a son and had begun to receive significant commissions. In the late 1460s he traveled to the mainland, perhaps journeying to Northern Italy and studying the work of Fra Angelico and Piero della Francesca, whose sense of volumetric proportions clearly influenced him. In time, Antonello became known for scenes from the Passion of Christ, Madonnas with the Child and secular portraits.

But it was a well-documented trip to Venice in 1475-76 that led to his greatest work-and to his major influence on such Venetian artists as Giovanni Bellini. In Venice Antonello painted the famous “Il Condottiere” (a three-quarter profile and an image of formidable resolution, now in the Louvre) and his masterpiece, the San Cassiano Altarpiece (a fragment of which is the pride of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna). Returning to Sicily, the artist combined Italian elegance and Flemish detail in his “Virgin Annunciate” (c. 1476), a mysterious, regal girl, and in a great Pietà (to which I will return). Antonello dictated his will in February 1479 and died a few months later.

‘Christ at the Column’

In these waning days of Lent, I turn to a second type of suffering Christ that Antonello developed after “Christ Crowned With Thorns.” It is Christ Bound to the Pillar, and the supreme example is arguably “Christ at the Column” (c. 1476-78, p. 24), in the Louvre. Here, with the column behind him, an anguished, bust-length Christ looks toward heaven as if in rapture. A braided crown of thorns sits on his thick auburn hair, drawing little blood; he has a light beard; a few delicately painted tears lie on his cheeks. The rope around his neck is knotted at the bottom center (adding to the illusion of depth), then falls over his right shoulder, behind his neck and down his left shoulder.

The desolation is extreme, but the body of the Lord suffers no disfigurement; the artist clearly chose psychological rather than merely physical revelation. The image draws us toward both heaven and earth, with a muted pathos unique to Antonello. The viewer, too, with the suffering Christ, looks for the mercy of God and for the fate of one’s fellow man. This is incarnation just before its final test.

The artist also painted three crucifixions. The simplest and most contemplative of these is a small votive panel (for private prayer), now in London’s National Gallery. While his other Crucifixions show the two thieves on either side of Jesus (not nailed to crosses but hung on trees), the London version shows only Jesus, a slender figure on a cross so high that he seems to float in the sky. Skulls surround the base of the cross. But Mary, to Jesus’ right, sits rapt in contemplation, while John, to the left, sits in prayer. You are bidden, humbly, to join them. Sit at the cross? you might ask. Yes, says the poet; imitate the mother and the apostle who will now be her son.

The ‘Dead Christ’

The startlingly contemplative mood also suffuses Antonello’s last painting, completed perhaps with the help of Jacobello: “Dead Christ Supported by an Angel,” which is sometimes called a Pietà, because the dead Christ is being mourned. One of the greatest treasures of the Prado in Madrid, this moderately sized panel has monumental effect. The dead subject sits almost upright in the center of the painting, the wound in his side still pouring blood; his head falls back, utterly helpless. Behind him, looking toward the viewer, a small angel weeps as he (implausibly) supports the Lord. Christ’s left hand falls into a space that is surrounded in the middle distance by skulls and bones. In the far background is the walled city of Messina, with its cathedral church and bell tower.

Here the depths of sorrow sound once more, but with a dignity and calm that draws us into the mystery. Stay; keep watch, you feel the painter say. This, in a searing yet serene image, is the revelation of sin and redemption all in one-and of love beyond telling.

I have never read that Antonello da Messina led a saint’s life. And there is often a gap (sometimes great) between an artist’s life and work. It is fairly certain that this artist was industrious in pursuing his painter’s profession and not averse to worldly recompense. But contemplating his panels, I felt a saintliness shining through. And what this artist offers us for Lenten prayer-or anytime-is saintly surely.

Leo J. O’Donovan, S.J., is president emeritus of Georgetown University.

Father Fernando Fernández Franco (born: San Sebastian, Spain 1941) as a young Jesuit was sent to the Gujarat Province in India. Having received a doctorate in economy, he taught 20 years at the University of Ahmedabad, while at the same time working at the Social Center. After some years as research director of the Indian Social Institute of the Society of Jesus in Delhi, Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach invited him in 2003 to become head of the Social Justice Secretariat in Rome. During these eight years he had the opportunity to visit and encourage almost all Jesuits working in the social apostolate throughout the world. During and after the 35th General Congregation he incorporated the issue of ecology and sustainability in the activity of the Social Justice Secretariat and guided the special task group on that issue. Now Fr. General has asked him to spend a couple of years at the African Jesuit Conference in Nairobi to help them in the development of a strategic apostolic plan.

Download ‘ Longtime publisher Michael Leach talks about his book Why Stay Catholic?‘ podcast

“We might think, If I had a better place to pray, I’d do it more. Or, If only I could live up in the mountains, or somewhere close to the ocean, I know I could connect better with God. This sort of thinking just gets in the way of all the wonder we could experience. God is not waiting for a more scenic spot in which to meet you. God knows that, no matter where you live, the Room is inside you anyway.”

-Vinita Hampton Wright, Days of Deepening Friendship