by James Martin, SJ

Today is the Feast of Blessed Pierre Favre, S.J., one of the early Jesuit companions, and an overlooked Jesuit hero. Often called the “Second Jesuit,” Favre was said by St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Society of Jesus, to be the man best suited to direct others in his Spiritual Exercises.

But Favre’s story is not nearly as well known as those of his two famous college roommates, Ignatius Loyola and Francis Xavier. (That so many books can’t even agree on a standard way of referring to the man–Pierre Favre, Peter Faver, Peter Favre, Peter Faber–is an indication of the lack of attention given him.) Below is a meditation on the life-changing friendship between Peter and his college roommates.

Friends in the Lord

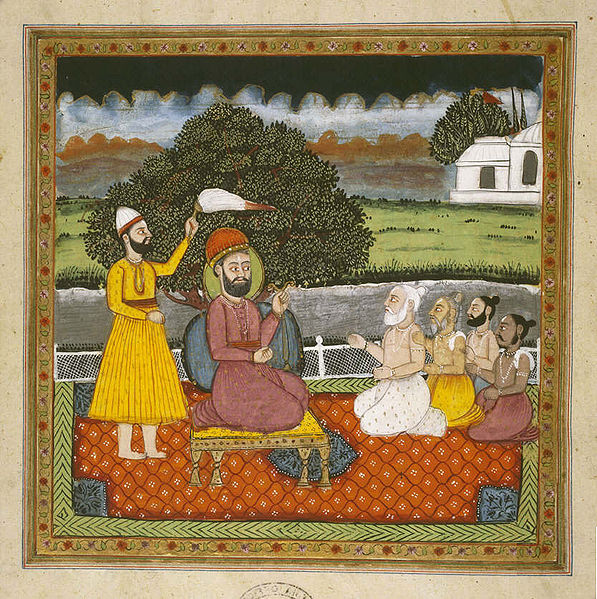

Ignatius, Peter and Francis

With his talent for friendships, Ignatius enjoyed close relations with a large circle of friends. (That is one reason for his enthusiasm for writing letters.) Indeed, the earliest way that Ignatius referred to the early Jesuits was not with phrases like “Defenders of the Faith” or “Soldiers of Christ,” but something simpler. He described his little band as “Friends in the Lord.”

Friendship was an essential part of his life. Two of his closest friends were his college roommates, Peter Favre, from the Savoy region of France, and Francisco de Javier, the Spaniard later known as St. Francis Xavier.

The three met at the Collège Sainte-Barbe at the University of Paris, then Europe’s leading university, in 1529. By the time they met Ignatius, Peter and Francis were already friends sharing lodgings. The two had studied for the last few years for their master’s degrees; both were excellent students. And both had heard stories about Ignatius before meeting him: the former soldier was a notorious figure on campus, known for his intense spiritual disciplines and habit of begging alms. At 38, Ignatius was much older than Peter and Francis, who were both 23 at the time. And his path to the university was more circuitous. After his soldiering career, his recuperation and his conversion, he had spent months in prayer trying to discern what to do with his life.

Ultimately, he decided that an education was required. So Ignatius went to school, taking elementary grammar lessons with young boys and, later, studying at the universities of Alcalá and Salamanca. His studies provide us with one of the more remarkable portraits of his newfound humility: the once-proud soldier squeezed into a too-small desk beside young boys in the classroom, making up for lost time.

Several years later, he enrolled at the University of Paris, where he met Favre and Xavier. There, in Favre’s words, they shared “the same room, the same table and the same purse.”

His commitment to a simple life impressed his new friends. So did his spiritual acumen. For Favre, a man troubled all his life by a “scrupulous” conscience, that is, an excessive self-criticism, Ignatius was a literal godsend. “He gave me an understanding of my conscience,” wrote Favre. Ultimately, Ignatius led Peter through the Spiritual Exercises, something that dramatically altered Favre’s worldview.

This happened despite some very different backgrounds. And here is one area where Ignatius and his friends highlight an insight on relationships: friends need not be cut from the same cloth. The friend with whom you the least in common may be the most helpful for your personal growth. Ignatius and Peter had, until they met, led radically different lives. Peter came to Paris at age 19 after what his biographer called his “humble birth,” having spent his youth in the fields as a shepherd. Imbued with a simple piety toward Mary, the saints, relics, processions, and shrines, and also angels, Peter clung to the simple faith of his childhood. Ignatius, on the other hand, had spent many years as a courtier and some of them as a soldier, undergone a dramatic conversion, subjected himself to extreme penances, wandered to Rome and the Holy Land in pursuit of his goal of following God’s will.

One friend had seen little of the world; the other much. One had always found religion a source of solace; the other had proceeded to God along a tortuous path.

Ultimately, Ignatius helped Peter to arrive at some important decisions through the freedom offered in the Spiritual Exercises. Peter’s indecision before this moment sounds refreshingly modern, much like the frustrating indecision of any college student today. He wrote about it in his journals:

Before that–I mean before having settled on the course of my life through the help given to me by God through Inigo–I was always very unsure of myself and blown about by many winds: sometimes wishing to be married, sometimes a doctor, sometimes a lawyer, sometimes a professor of theology, sometimes a cleric without a degree–at times wishing me to be a monk.

In time, Peter decided to join Ignatius on his new path, whose ultimate destination was still unclear. Peter, sometimes called the “Second Jesuit,” was enthusiastic about the risky venture from the start. “In the end,” he writes, “we became one in desire and will and one in a firm resolve to take up the life we lead today….” His friend changed his life. Later, Ignatius would say that Favre was the most skilled of all the Jesuits in giving the Spiritual Exercises.

Ignatius would change the life of his other roommate, too. Francisco de Jassu y Javier, born in 1506, in the castle of Javier, was an outstanding athlete and student. He began his studies in Paris at the age of 19. Every biographer describes Francis as a dashing young man with boundless ambition. “Don Francisco did not share the humble ways of Favre,” wrote one.

Francis Xavier was far more resistant to change than Peter Favre had been. Only after Peter left their lodgings to visit his family, when Ignatius was alone with the proud Spaniard, was he was able to slowly break down Xavier’s stubborn resistance. Legend has it that Ignatius quoted a line from the New Testament, “What does it profit them if they gain the world, but lose or forfeit themselves?” As John W. O’Malley writes in The First Jesuits, Francis’s conversion was “as firm as Favre’s but more dramatic because his life to that point had shown signs of more worldly ambitions.”

It is impossible to read the journals and letters of these three men–Ignatius the founder, Xavier the missionary, and Favre the spiritual counselor–without noticing the differences in temperaments and in talents.

In later years Ignatius would become primarily an administrator, guiding the Society of Jesus through its early days, spending much of his time laboring over the Jesuit Constitutions. Xavier became the globetrotting missionary sending back letters crammed with hair-raising adventures to thrill his brother Jesuits. (And the rest of Europe, too: Xavier’s letters were the equivalent of action-adventure movies for Catholics of the time.) Favre, on the other hand, spent the rest of his life as a spiritual counselor sent to spread the Catholic faith during the Reformation. His work was more diplomatic, requiring artful negotiation through the variety of religions wars at the time.

Their letters reveal how different were these three personalities. They also make it easy to see how much they loved one another. “I shall never forget you,” wrote Ignatius in one letter to Francis. And when, during his travels, Xavier received letters from his friends he would carefully cut out their signatures, and keep them with him–“as a treasure,” in the words of his biographer Georg Schurhammer, S.J.

Here is Francis Xavier, writing from India, in 1545, to his Jesuit friends in Rome, expressing love for his faraway friends.

God our Lord knows how much more consolation my soul would have from seeing you than from my writing such uncertain letters as these to you because of the great distance between these lands and Rome; but since God has removed us, though we are so much alike in spirit and in love, to such distant lands, there is no reason…for a lessening of love and care in those who love each other in the Lord.

The varied accomplishments of Ignatius, Francis and Peter began with the commitment that they made to God and to one another in 1534. In a chapel in the neighborhood of Montmartre in Paris, the three men, along with four other new friends from the university–Diego Laynez, Alfonso Salmerón, Simon Rodrigues, and Nicolás Bobadilla–pronounced vows of poverty and chastity together. Together they offered themselves to God. (The other three men who would round out the list of the “First Jesuits,” Claude Jay, Jean Codure and Paschase Broët, would join after 1535.)

Even then friendship was foremost in their minds. Laynez, noted that though they did not live in the same rooms, they would eat together whenever possible, and have frequent friendly conversations, cementing what one Jesuit writer called “the human bond of union.” In a superb article in the series Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits, entitled “Friendship in Jesuit life,” Charles M. Shelton, S.J., the professor of psychology, writes, “We might even speculate whether the early Society would have been viable if the early companions had not enjoyed such a rich friendship.”

The mode of friendship among the early Jesuits flowed from Ignatius’s “way of proceeding.” For want of a better word, they did not try to possess one another. In a sense, it was a form of poverty. Their friendship was not self-centered, but other-directed, seeking the good of the other. The clearest indication of this is the willingness of Ignatius to ask Francis to leave his side and become one of the church’s great missionaries.

It almost didn’t happen. The first man that Ignatius wanted to send for the mission to “the Indies” fell ill. “Here is an undertaking for you,” said Ignatius. “Good,” said Francis, “I am ready.” Ignatius knew that if he sent Francis away he might never see his best friend again.

So did Francis. In a letter written from Lisbon, Portugal, Francis writes these poignant lines as he embarks. “We close by asking God our Lord for the grace of seeing one another joined together in the next life; for I do not know if we shall ever see each other in this….Whoever will be the first to go to the other life and does not find his brother whom he loves in the Lord, must ask Christ our Lord to unite us all there….”

During his travels, Xavier would write Ignatius letters, not simply reporting on the new countries that he had explored and the new peoples he was encountering, but expressing his continuing fondness. Both missed one another, as good friends do. Both recognized the possibility that one would die before seeing the other again.

“[You] write me of the great desires that you have to see me before you leave this life,” wrote Francis. “God knows the impression that these words of great love made upon my soul and how many tears they cost me every time I remember them.” Legend has it that Francis knelt down to read the letters he received from Ignatius.

Francis’s premonitions were accurate. After years of grueling travel that took him from Lisbon to India to Japan, Francis stepped aboard a boat bound for China, his final destination. In September 1552, twelve years after he had bid farewell to Ignatius, he landed on the island of Sancian, off the coast of China. But after falling ill with a fever, he was confined to a hut on the island, tantalizingly close to his ultimate goal. He died on December 3, and his body was first buried on Sancian and then brought back to Goa, in India.

Several months afterwards, and unaware of his best friend’s death, Ignatius living in the Jesuit headquarters in Rome, wrote Francis asking him to return home.

From The Jesuit Guide to Almost Everything. For a short biography of Blessed Peter Favre, see this excerpt from Jesuit Saints and Martyrs, by Joseph Tylenda, S.J. The best (and mos accessible) biography of Favre is The Quiet Companion, by Mary Purcell. It is currently out of print but well worth tracking down.

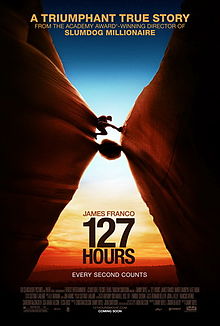

insignificance of human beings. It is based on the true story of Aaron Ralston as told in his book Between A Rock And A Hard Place. He was an extreme outdoor sportsman who unfortunately got trapped in a narrow ‘slot’ canyon, his hand caught by a falling boulder. There is no getting away from this next gruesome detail: that he has to sever part of his arm to escape. It is a fairly simple but dramatic story that is worked to maximum effect by director Danny Boyle, of Trainspotting and Slumdog Millionaire.

insignificance of human beings. It is based on the true story of Aaron Ralston as told in his book Between A Rock And A Hard Place. He was an extreme outdoor sportsman who unfortunately got trapped in a narrow ‘slot’ canyon, his hand caught by a falling boulder. There is no getting away from this next gruesome detail: that he has to sever part of his arm to escape. It is a fairly simple but dramatic story that is worked to maximum effect by director Danny Boyle, of Trainspotting and Slumdog Millionaire.