St. Hilary of Poitiers

“They didn’t know who they were.” This is how Hilary summed up the problem with the Arian heretics of the fourth century.

Hilary, on the other hand, knew very well who he was — a child of a loving God who had inherited eternal life through belief in the Son of God. He hadn’t been raised as a Christian but he had felt a wonder at the gift of life and a desire to find out the meaning of that gift. He first discarded the approach of many people who around him, who believed the purpose of life was only to satisfy desires. He knew he wasn’t a beast grazing in a pasture. The philosophers agreed with him. Human beings should rise above desires and live a life of virtue, they said. But Hilary could see in his own heart that humans were meant for even more than living a good life.

If he didn’t lead a virtuous life, he would suffer from guilt and be unhappy. His soul seemed to cry out that wasn’t enough to justify the enormous gift of life. So Hilary went looking for the giftgiver. He was told many things about the divine — many that we still hear today: that there were many Gods, that God didn’t exist but all creation was the result of random acts of nature, that God existed but didn’t really care for his creation, that God was in creatures or images. One look in his own soul told him these images of the divine were wrong. God had to be one because no creation could be as great as God. God had to be concerned with God’s creation — otherwise why create it?

At that point, Hilary tells us, he “chanced upon” the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. When he read the verse where God tells Moses “I AM WHO I AM” (Exodus 3:14), Hilary said, “I was frankly amazed at such a clear definition of God, which expressed the incomprehensible knowledge of the divine nature in words most suited to human intelligence.” In the Psalms and the Prophets he found descriptions of God’s power, concern, and beauty. For example in Psalm 139, “Where shall I go from your spirit?”, he found confirmation that God was everywhere and omnipotent.

But still he was troubled. He knew the giftgiver now, but what was he, the recipient of the gift? Was he just created for the moment to disappear at death? It only made sense to him that God’s purpose in creation should be “that what did not exist began to exist, not that what had begun to exist would cease to exist.” Then he found the Gospels and read John’s words including “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God…” (John 1:1-2). From John he learned of the Son of God and how Jesus had been sent to bring eternal life to those who believed. Finally his soul was at rest. “No longer did it look upon the life of this body as troublesome or wearisome, but believed it to be what the alphabet is to children… namely, as the patient endurance of the present trials of life in order to gain a blissful eternity.” He had found who he was in discovering God and God’s Son Jesus Christ.More……

Stigmata

What you have long suspected is true… I am a secret mystic. Look at my stigmata!

I probably shouldn’t admit that I got it from a panicked and over-enthusiastic use of a toilet plunger, should I?

Pope Francis celebrates Mass at Jesuit mother church

Vatican Radio

Pope Francis celebrated Mass on Friday morning in the mother church of the Jesuit order, the church of the Gesù, to mark the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus and to give thanks for the enrollment of the first Jesuit to be ordained a priest, Fr Peter Faber SJ, in the list of the saints.

In his homily, Pope Francis spoke of the particular way in which the Jesuit Order is marked – and desires to be signed – by the name of Jesus: “To march,” he said, “beneath the standard of His Cross.” Pope Francis went on to explain that this means sharing in and having Christ’s very own sentiments. “It means,” he said, “to think like Him, to love like Him, to see [things the way He sees them], to walk like Him – it means doing what He did, and with the same sentiments He had, with the sentiments of His heart.”

Pope Francis went on to discuss the great example of his holy confrere, St Peter Faber, whose sainthood the Holy Father officially recognized and proclaimed on December 17th of last year. “Under the guidance of St. Ignatius,” explained Pope Francis, “[the man who would become St Peter Faber, SJ] learned to combine his restless – but also sweet and even,” said Pope Francis, “exquisite sensitivity, with the ability to make decisions: he was a man of great desires,” Pope Francis said, “he recognised his desires and he owned them. Indeed, for Faber, it is precisely in the moment in which difficult things are proposed, that the true spirit that moves to action manifests itself.” Pope Francis added, “An authentic faith always implies a deep desire to change the world.”

Speaking of temptation…

Over the Christmas break, I was given some insights but little joy in my spiritual reading. The emotions we experience in prayer and spiritual reading are, of course, incidental; it is the insights (and the transformations occasioned by them) that are important. And when I say I was given little joy, I mean that my greatest insights so far during this Christmas Season have been insights into the nature of sin-including, above all, my own sins.

The first and most telling of these leapt out at me when reading the last chapters of St. Matthew’s Gospel. You may well take me for an idiot; surely I should have been reading the early chapters of the gospels at this time of year. But I am content to leave this to Providence; for whatever reason, that’s where I was in my reading and rereading of Scripture. Therefore, I call your attention to chapter 26, verses 14 and 15: “Then one of the twelve, who was called Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests and said, ‘What will you give me if I deliver him to you?'”

How many times have I heard or read this passage? And yet on this occasion the nature of all temptation suddenly became crystal clear to me. For each temptation represents the possibility of gain in return for a betrayal. And each time we entertain a temptation, we ask the same question as Judas: What will you give me if I deliver him to you?

This is not just a matter of money, though it can be about money. Perhaps I have an opportunity to ridicule someone else to make myself appear superior. As I look at this possibility, I ask in effect, “What will you give me if I deliver him to you?” Or maybe, without being detected, I can shirk some responsibility in favor of enjoying some recreation. “What will you give me,” I ask of this situation, “if I deliver him to you?” In exactly the same way, when I entertain a temptation against purity, I am really asking the question once again: “What will you give me if I deliver him to you?”

For Judas, “you” stood for the group of chief priests, who were a temptation to him; but we can take “you” to refer to any temptation. The nature of temptation is always personal, exciting our wayward desires. There is always something we hope to gain from it. And the requirement to obtain this gain is always the same: The betrayal of our Creator and Lord.

A Second Insight for the Righteous

Since this insight brought me so little joy, I sought relief in a little book with a highly encouraging title, A Little Garden of Roses by Thomas à Kempis, the famous fifteenth-century author of The Imitation of Christ. It seems that in addition to the Imitation, Thomas wrote two small collections of meditations on virtue for the monks of his community. A Little Garden of Roses was followed by a similar work entitled The Valley of Lilies. Both have been published anew in a single volume from Ignatius Press, Bountiful Goodness: Spiritual Meditations for a Deeper Union with Christ. You can see from the titles why I turned here for encouragement.More……

Is it truly un-Islamic to respect Christmas?

Together, Muslims and Christians constitute over 95 percent of Indonesia’s population. If they do not live in harmony then the country is in huge trouble.

Despite the media hyperbole, the overwhelming majority of Indonesian Muslims and Christians do live in peace, but the increasingly visible cases of discrimination, including the sealing of several churches, is indeed alarming.

The warning from our law enforcers of attacks during the Christmas season is another grim reminder that our longing for religious tolerance remains divorced from reality.

The bias against the religious minority is indisputably repugnant, based on the tenets of democracy, liberalism and secularism. But for those behind the discrimination, it barely matters as they believe that their one and only mission in life is to pursue God’s blessings. The lecture on the creeds of John Locke, Montesquieu or even Pancasila, will fall on deaf ears among those who venerate the words of God and the instruction of His prophet above everything else.

So the big question then is whether Islam really preaches hostility against those who espouse different faiths, especially Christians? If that is the case then those who claim to defend the faith by repressing others would be vindicated.

There are ample commandments in the Koran exhorting peaceful coexistence with non-Muslims. The Koran calls for Muslims to spread the message of Islam but the scripture also stipulates that there is no compulsion in religion (Al-Baqarah/2:256), for you is your religion and for me is mine (109:6), the Prophet is only a reminder not a controller over others (88:21-22).

There are some verses that can be misconstrued as promoting violence, “Allah does not forbid you from those who do not fight you because of your religion and do not expel you from your homes – from being righteous toward them and acting justly toward them. Indeed, Allah loves those who act justly” (60:8).

The aversion that some Muslims harbor against Christians is strikingly peculiar not only because of the Koran aforementioned general injunctions for religious tolerance but especially because Muslims and Christians share a myriad of things in common.

It would be disingenuous to claim that Christianity and Islam are identical considering they do have some fundamental differences. Nevertheless, it would also be misleading to argue that Islam and Christianity are antithetical.

Apart from Christianity, Islam is the only world’s main religion that recognizes Jesus or Isa as more than just an ordinary human being. While Islam does not accept him as the son of God, Islam still holds Isa in a high esteem as one of God’s prophets who delivered His words, a messenger who performed many miracles, including his birth from a virgin, someone that those who declare to be Muslims are compelled to revere.

Full Story: Is paying respects to Christmas un-Islamic?

Source: Jakarta Post

St. John

St. John, the son of Zebedee, and the brother of St. James the Great, was called to be an Apostle by our Lord in the first year of His public ministry. He became the “beloved disciple” and the only one of the Twelve who did not forsake the Savior in the hour of His Passion. He stood faithfully at the cross when the Savior made him the guardian of His Mother. His later life was passed chiefly in Jerusalem and at Ephesus. He founded many churches in Asia Minor. He wrote the fourth Gospel, and three Epistles, and the Book of Revelation is also attributed to him. Brought to Rome, tradition relates that he was by order of Emperor Dometian cast into a cauldron of boiling oil but came forth unhurt and was banished to the island of Pathmos for a year. He lived to an extreme old age, surviving all his fellow apostles, and died at Ephesus about the year 100.

St. John is called the Apostle of Charity, a virtue he had learned from his Divine Master, and which he constantly inculcated by word and example. The “beloved disciple” died at Ephesus, where a stately church was erected over his tomb. It was afterwards converted into a Mohammedan mosque.

John is credited with the authorship of three epistles and one Gospel, although many scholars believe that the final editing of the Gospel was done by others shortly after his death. He is also supposed by many to be the author of the book of Revelation, also called the Apocalypse, although this identification is less certain.

Pope Francis Visits Pope Benedict To Wish Him A Merry Christmas

Pope Francis made a Christmas visit to Pope Emeritus Benedict yesterday (Dec 23) and said he found his 86-year-old predecessor looking well, according to television footage released by the Vatican.

Pope Francis, who was elected in March, spent about 30 minutes with Pope Emeritus Benedict in an ex-convent on the Vatican grounds where the former pope has been living in near isolation.

“It’s a pleasure to see you looking so well,” Pope Francis told Pope Emeritus Benedict, who in February became the first pope in 600 years to step down instead of ruling for life.

Television footage released by the Vatican – only the fourth time Benedict has been filmed since his resignation – showed him looking alert and in better health than on previous occasions.

He greeted Francis, 77, at the door of the residence, standing with an ivory-handled wooden cane. They walked to a chapel where they stood and prayed before speaking privately in another room.

When Pope Francis left Pope Emeritus Benedict, he said, “Merry Christmas, pray for me.” Pope Emeritus Benedict responded, “Always, always, always”.

Pope Emeritus Benedict resigned on Feb 28, saying he no longer had the physical and spiritual strength to lead the 1.2 billion member Roman Catholic Church. REUTERS

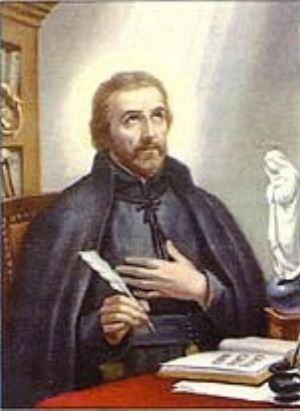

St. Peter Canisius

He was born in 1521 in Nijmegen in the Duchy of Guelders, which, until 1549, was part of the Habsburg Netherlands within the Holy Roman Empire and is now the Netherlands. His father was the wealthy burgermeister, Jacob Kanis; his mother, Ægidia van Houweningen, who died shortly after Peter’s birth. He was sent to study at the University of Cologne, he earned a Master’s degree in 1540, at the age of 19. While there, he met Peter Faber, one of the founders of the Society of Jesus. Through him, Canisius became the first Dutchman to join the newly founded Society of Jesus in 1543.

Through his preaching and writings, Peter Canisius became one of the most influential Catholics of his time. He supervised the founding and maintenance of the first German-speaking Jesuit colleges, often with little resources at hand. Because of his frequent travels between the colleges, a tedious and dangerous occupation at the time, he became known as the Second Apostle of Germany.

Canisius also exerted a strong influence on the Emperor Ferdinand I; he ceaselessly reminded Ferdinand of the imminent danger to his soul should he concede more rights to Protestants in return for their military support. When Canisius perceived a very real danger of Ferdinand’s son and heir, Maximilian, openly declaring himself a Protestant, Canisius threatened Maximilian with disinheritance should he desert the Catholic Faith.

Canisius was an influential teacher and preacher, especially through his “German Catechism”, a book which defined the basic principles of Catholicism in the German language and made them more accessible to readers in German-speaking countries. He was offered the post of Bishop of Vienna in 1554, but declined in order to continue his traveling and teachings. He did, however, serve as administrator of the Diocese of Vienna for one year, until a new bishop was appointed for it.

He moved to Germany, where he was one of the main Catholic theologians at the Colloquy of Worms in 1557, and later served as the main preacher in the cathedral of Augsburg from 1559 to 1568, where he strongly witnessed to his faith on three or four occasions each week. His preaching was said to have been so convincing that it attracted hundreds of Protestants back to the old faith.

By the time he left Germany, the Society of Jesus in Germany had evolved from a small band of priests into a powerful tool of the Counter Reformation. Canisius spent the last 20 years of his life in Fribourg, Switzerland, where he founded the Jesuit preparatory school, the College of Saint Michael, which trained generations of young men for careers and future university studies.

In 1591, at the age of 70, Canisius suffered a stroke which left him partially paralyzed, but he continued to preach and write with the aid of a secretary until his death in Fribourg. He was initially buried at the Church of St. Nicholas. His remains were later transferred to the church of the Jesuit College, which he had founded and where he spent the last year of his life They were interred in front of the main altar of the church, and the room he occupied during those last months is now a chapel which is open to the veneration of the faithful.

Jesuit Arts

James Martin, SJ

Members of the Society of Jesus are often accused of excessive pride in their order and its history. This can be a fair critique. Sometimes, for example, Jesuits speak as if St. Ignatius Loyola were the first Christian to discover prayer. Not long ago at a retreat house, I gave a talk about Ignatian spirituality, which prompted a Benedictine in the audience to say, with good nature, You know, St. Benedict used to pray from time to time too! But there are some things of which the Jesuits and their colleagues can be justly proud, and for which they can be abundantly grateful to God. Their record in the arts is among them.

A newly published book, Jesuits and the Arts: 1540-1773, is the first comprehensive survey of the worldwide artistic enterprise of the early Society of Jesus. By any measure, this new volume is brilliantly conceived, consistently fascinating and absolutely gorgeous to look at. Beginning with a chapter entitled Saint Ignatius and the Cultural Mission of the Society of Jesus, written by John W. O’Malley, S.J., the study takes the reader on a journey through the history of Jesuit architecture in Europe (including an entire chapter on the Church of the Gesù in Rome); the influence of the Society on Italian Renaissance and Baroque painting; the surprising story of Jesuit theater; the artistic, and especially architectural, heritage of the Jesuits in Latin America (including the legacy of the Reductions in South America, made well known by the movie The Mission); and the Jesuit-influenced artistic achievements in North America and Asia. Jesuits and the Arts represents the first time that these disparate threads have been pulled together in a single volume.

This impressive work of scholarship, boasting contributions from an array of experts from Italy, Spain, Germany, France, Argentina and the United States, has been edited by Father O’Malley, professor of church history at Weston Jesuit School of Theology, in Cambridge, Mass., and Gauvin Alexander Bailey, professor of art history at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. (An earlier version of the book appeared in 2003 in Italian, French and Spanish, edited by Giovanni Sale, S.J.)

The book’s scholarship is more than matched by the full-color images that crowd every page. Quite simply, this is one of the most beautiful books I have ever seen. It continues the new tradition of richly made books from St. Joseph’s University Press, which published another lovely book in 2002 entitled Stained Glass in Catholic Philadelphia, whose prosaic title belies the book’s depth of scholarship and the beauty of its pages.

Jesuits and the Arts arrives at a propitious time. Starting this month, the Society of Jesus will begin celebrating what it is calling a jubilee year, marking three important Jesuit anniversaries. Five hundred years ago St. Francis Xavier, the great missionary, was born. So was Blessed Peter Faber, a Jesuit somewhat less well known among the general public, but who was said by Ignatius to be the best giver of the Spiritual Exercises in his time. The Society of Jesus and its colleagues will also mark in 2006 the 450th anniversary of the death of St. Ignatius.

So perhaps the Jesuits and their co-workers can, at least for the next year or so, be forgiven for showing some pride and being just a little more grateful to God. To share in our celebration we offer over these next few pages a sampling of images from Jesuits and the Arts.

In the print version of America, this article is accompanied by photos from Jesuits and the Arts: 1540-1773.

James Martin, S.J., is an associate editor of America.

Siena Duomo (Siena Cathedral)

Siena’s Cathedrale di Santa Maria, better known as the Duomo, is a gleaming marble treasury of Gothic art from the 13th and 14th centuries.

History

Siena’s Duomo was built between 1215 and 1263 and designed in part by Gothic master Nicola Pisano. His son, Giovanni, drew up the plans for the lower half of the facade, begun in 1285. The facade’s upper half was added in the 14th century.

The 14th century was a time of great wealth and power for Siena, and plans were made to expand the cathedral into a great church that would dwarf even St. Peter’s in Rome. The already-large Duomo would form just the transept of this huge cathedral.

Expansion got underway in 1339 with construction on a new nave off the Duomo’s right transept. But in 1348, the Black Death swept through the city and killed 4/5 of Siena’s population. The giant cathedral was never completed, and the half-finished walls of the Duomo Nuovo (New Cathedral) survive as a monument to Siena’s ambition and one-time wealth.

In the 19th century, the cathedral was extensively restored, including the addition of golden mosaics on the facade.

What to See

Large in scale and ornately decorated inside and out, Siena’s cathedral is one of the finest examples of Italian Gothic architecture.

The Duomo’s unique black-and-white striped campanile dates from 1313, but reflects the Romanesque style. The tall, square belltower has increasing numbers of round-headed arcades with each level and culminates in a pyramid-shaped roof.

The south transept has an entrance known as the Porto del Perdono (Door of Forgiveness), which is topped with a medallion bust of the Virgin and Child by Donatello (original in the Museo dell’Opera). On the north side of the cathedral, a stone set into the wall is inscribed with the mysterious Sator Square.

The west facade was begun in 1285 with Giovanni Pisano as the master architect. He completed the lower level by 1297, at which time he abruptly left Siena over creative differences with the Opera del Duomo. Camaino di Crescentino took over from 1299 until 1317, when the Opera ordered all work to focus on the east end of the cathedral. Attention finally returned to the facade in 1376, with a new design inspired by the newly built facade of Orvieto Cathedral.

Parts of the facade were restored and reorganized in 1866-69 by Giuseppe Partini and again after World War II. All the statues on the facade, many of them designed by Giovanni Pisano, were replaced with replicas in the 1960s; the originals are displayed in the Museo dell’Opera. Pisano’s statues depict Greek philosophers, Jewish prophets and pagan Sibyls, each accompanied by an inscription, as well as animals including lions and griffins.