Notes From Underground

by Nicholas Clifford

Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian has been one of the most important and controversial figures in modern Chinese Catholicism. Born into a Catholic family in Shanghai in 1916, he was educated by the French Jesuits in that city and became a Jesuit himself, living through a tumultuous time in China’s history, a witness to war and revolution, to the triumph of Mao’s Communists in 1949 and the vicious campaigns mounted against China’s Christians (to say nothing of other perceived enemies of Maoism) in the years that followed.

Jailed in 1955, he emerged only in 1982 as Maoist Communism was giving way to a powerful state capitalism disingenuously waving the revolution’s red flag. By that time, Chinese Christians, both Protestant and Catholic, had been divided into two groups. One was underground, in the Catholic case maintaining a traditional loyalty to Rome. The other came to terms with the regime in the Catholic Patriotic Association. After Jim’s release in 1982, he became not only one of the leaders of this latter movement, but as the C.P.A.’s bishop of Shanghai, proved himself very successful in rebuilding Shanghai Catholicism, reopening churches, schools and seminaries, and attracting (or re-attracting) parishioners. To some (including many of his fellow Jesuits) he was a traitor; to others, a man of extraordinary accomplishments under extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

This volume, splendidly translated by William Hanbury-Tenison, takes the story only up to Jin’s return to Shanghai from jail in 1982. His accounts of his youth and education under the French Jesuits in Shanghai are very interesting, as are those of his studies abroad after the Second World War in Rome and in France. Sometimes gently and sometimes not, he chides the French clerical establishment in Shanghai for seeking to hold onto power and ignoring the efforts of men like Benedict XV and his nuncio in China, Celso Constantini, to encourage the indigenization of the church (Benedict’s “Maximum Illud” of 1919 is one of the key documents here).

I do not think he’s exaggerating. When the first Chinese bishops since the 17th century were named by Rome in the mid-1920s, a dispatch from the French minister that I found in the archives of the Quai d’Orsay warned that they would become heretics “par la pente naturelle de leur ésprit” (from their natural inclinations), and would use their positions for their own benefit. That seems to have been a common French view, both lay and clerical. And if Jin’s account is to be trusted, even after the coming of the Maoist regime in 1949, and the installation of Bishop Gong Pinmei in 1950, the French Jesuits sought to maintain control, presumably as what the Chinese call houtai laoban, or backstage manipulators.

Not that it did much good. By the early 1950s most foreign missionaries, Protestant and Catholic, either fled China, were expelled or were jailed. As long as he could, Gong led an effort to prevent the regime from taking over the city’s Catholicism, an episode described in Church Militant, the masterful account of the period by Paul Mariani, S.J. By September 1955, however, a series of sweeping arrests brought independent Shanghai Catholicism pretty much to an end. Gong and Jin themselves were among the many arrested and jailed, and much of the latter half of the book is given over to Jin’s prison years, with endless interrogations and forced confessions of supposed activities against the regime. He kept his faith alive, however, and though the book ends with his release in 1982, a few years later, at the urging of his former captors, he formally joined the C.P.A. “In another twenty years,” they told him, “you will go to heaven, and Catholicism will simply die out in China. You will bear responsibility for that…. You should take responsibility for the Church.” He did so, becoming bishop of Shanghai under C.P.A. auspices and going about the task of rebuilding Catholicism there, with remarkable success until his death in 2013.

Whatever Jin’s ecclesiastical opponents may have said of him earlier, his relations with Rome were patched up when the Vatican ultimately recognized him as bishop coadjutor. Nevertheless, he remains a figure of controversy because of his dealings with Beijing; and while C.P.A. members in Shanghai may have something that looks a bit like religious freedom, the so-called “underground” church, which has never renounced allegiance to Rome, continues to be watched, harassed and persecuted.

For much of this, Jin’s record remains extraordinarily valuable. But not definitive. Memoirs are not, properly speaking, history. Rather, they are part of the raw material of history, waiting for historians to come along and incorporate them into their broader research, seeking to arrive at clearer and more accurate depictions of the past than have earlier existed. By their very nature, memoirs must be personal and indeed parochial, setting forth the views of single individuals. More than that-and this is a quality they share with all historical writing-they can be deceptive, even though this may not be the intent of the writer, and even though every event they record did actually happen.

Jin’s book, he tells us, was written entirely from memory, since he had lost all his papers at the time of his arrest and knew the dangers of keeping correspondence or a journal. Add to these uncertainties the fact that it was published in China, hardly a leading center of press freedom. His translator told me in an email that he worked from a privately printed copy of the memoirs that had not undergone censorship by the authorities of the People’s Republic of China, though Jin may well have censored it himself, well knowing what he could and could not say. Parts of the book sound like echoes of Beijing’s standard phrases and judgments. When, for example, Jin refers to the “Gong Pinmei counter-revolutionary clique,” or sees Bishop Gong as a front for the French Jesuits, is he reflecting his own beliefs, or does he trust us to discover a meaning beyond the words themselves? He is quite ready to denounce the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), though that is almost orthodoxy in today’s People’s Republic of China, but he says nothing of Mao’s catastrophic famine of the late 1950s, which carried away from 30 million to 45 million victims in three years.

It is impossible to know the answers to these questions. Read his work and decide for yourself. But read Mariani’s Church Militant as well, which is based on a wide range of official and unofficial sources, both Chinese and Western. Bear in mind also that the Chinese state’s wish to control certain ecclesiastical affairs is by no means a recent Communist invention. In 845, under the Tang dynasty, a widespread persecution of Buddhism and other religions (including Nestorian Christianity) broke out, at least in part, because they were seen as foreign and perhaps even a danger to the established order. Thereafter the state, when it could, kept a wary eye on such matters. Nor, for that matter, is the church’s acquiescence-forced or otherwise-to the cultural and political norms of the day anything new. The road to Canossa has not always been a one-way street. Think, for example, of the Gallican articles of 1682 or, much more recently, the Emperor Franz Josef’s veto of Cardinal Mariano Rampolla as the elected successor of Pope Leo XIII in 1903 or Francisco Franco’s power to name his own bishops in Spain.

I am not a church historian, and will leave the similarities and differences here to others. Bishop Jin Luxian has great admirers, both within the church and beyond it. Did he make the right choice in accepting state supervision of his eminently successful rebuilding of Shanghai Catholicism? It is very tempting to say that he did. Now that he has died, however, it is unlikely that we will ever see the second volume of these memoirs, or know the circumstances behind their publication even if they appear. Nor is the story over yet. Shortly after Jin’s death in April 2013, his successor as bishop, Ma Daqin, resigned his position in the C.P.A., and was thereupon ousted by the regime. His status and whereabouts are something of a mystery today.

Nicholas Clifford is an emeritus professor of history at Middlebury College in Vermont.

Fr. Peter Li Chin-sheng went peacefully to the Lord

Dear friends in Christ,

Fr. Peter Li Chin-sheng went peacefully to the Lord on July 3, 2014 at the Cardinal Tien Hospital, Taipei, at 8:48 p.m.

Fr. Li was born in Houchizhuang, Daming, Hebei, on Aug. 1, 1920. He entered the Society in Xujiahui (Zikawei), Shanghai, on Aug. 30, 1943, was ordained to the priesthood on June 17, 1950 at St. Mary’s Cathedral, San Francisco, and professed the last vows on Feb. 2, 1959 in Taipei, Taiwan.

Yours in Our Lord,

Society of Jesus,

Chinese Province

July 3, 2014

Opening message for the EYM Centennial Jubilee Year

Dear friends

The EYM is to live in friendship with Jesus. From the beginning Jesus chose friends to accompany him in his daily life and in his mission of announcing to the world the love of his Father. It was a beautiful mission that filled his heart with joy.

During these last one hundred years, as the Eucharistic Crusade and as the Eucharistic Youth Movement we also have been invited to share that joy and friendship. This is a great privilege that we celebrate with gratitude. One hundred years walking with Jesus, in so many countries and cultures, with numerous generations that have passed through our groups learning His way to live and love!

By this message we solemnly open the Jubilee Year of the Eucharistic Youth Movement. It will go from this coming June 22, the feast of Corpus Christi, the international day of our Movement, until the big World Gathering in Rome from August 4 to 10 2015.

The motto of our Jubilee Year and meeting in Rome is “So that my joy may be in you”, taken from the gospel of John 15:11.

What is the meaning of celebrating this Jubilee and Centennial? In the first place, we want it to help us to live the joy of Jesus’ friendship. We feel invited to come closer to his Heart and more committed to our service in the heart of the world.

We suggest two sources of inspiration for this year. As of now, we can start using them for our spiritual preparation of this important moment:

- The words Jesus said to his disciples in the context of the Last Supper, John 15,9-17, when he speaks of love and friendship

- The apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium in which our dear Pope Francis challenges us to live and announce the gospel (especially numbers 1 – 17 and 275 – 283)

The Jubilee Year has a calendar that has been announced and that we copy again at the end of this letter. We rely on your creativity and initiative to make these proposals a reality for your people.

Preparation for the big World Gathering in Rome next year has already begun. All EYM members over 15 are invited. We expect the delegations will be formed mainly by young people. We encourage the AP/EYM adults to financially support the participation of the youth.

The Italian EYM is working to welcome us in simple structures that will not demand housing fees on behalf of the participants: our operation base and sleeping place will be the Collegio Massimo, the Jesuit High School of Rome. There will be two registration fees: 80 Euros for those that come from outside Europe, and 150 Euros for the European EYM. We know the cost of the trip is very high for many of you. Unfortunately we will not have the possibility to sponsor any travel costs, so this means you should start getting organized as of now in order to be there.

We are working on the program of that week in Rome. Arrivals will be on August 4 and departures the 10th. There will be many moments to share and celebrate the rich multicolor diversity of the worldwide EYM. We are sure it will be an incredible week! We know you will do your best efforts to make it. As we write this letter, we still don’t know the Holy Father’s response to our request for a private audience. If we do not have it, we will meet him anyhow at Saint Peter’s Square together with the other pilgrims.

With this letter we send you the official prayer for the Centennial (see Annex 1). We kept the same prayer we used for the Congress in Argentina in 2012. Pray it in your meetings to warm up the heart for our big Gathering. We also attach the official logo.

A group of EYM artists are already working on the official hymn of the Gathering that should be ready in a few months. But just the same, in addition to our official hymn, we invite the EYM from all over the world to compose a hymn on the Centennial. We will have the chance to share and sing your songs once in Rome.

It will be wonderful to have you in Rome next year!

Warm Paschal greetings.

For the EYM,

Claudio, sj, former Director General Delegate

Frédéric, sj, Director General Delegate

Lourdes, rjm, international Assistant

International Conference on Ignatian Spirituality 2014

|

This year, the Society of Jesus around the world celebrates the 200th anniversary of Restoration. To commemorate this, all the Jesuits and the related Ignatian families are called to a deeper reflection and renewal of our vocation in following Christ.

Xavier House-Ignatian Spirituality Center, faithful to Ignatian tradition in this juncture of history, wants to follow the inspiration of St. Ignatius to draw out the treasure of his legacy for our times. Taking this opportunity, we are going to organize an Ignatian Spirituality Conference as the summit of this celebration.

In this Conference, apart from the keynote speeches by renowned international speakers, there are also a selection of workshops with various interesting and practical topics to foster spiritual conversations and further learning.

We cordially invite you to join this Ignatian journey, to share, refresh and reflect together in this meaningful gathering. We hope that this conference also serves as our ongoing and deepening journey to God, with Ignatius as our guide and companion.

Conference Overview

Official Website: http://goo.gl/yqo8RG

Shanghai’s Bishop Ma to remain in confinement

Auxiliary Bishop Thaddeus Ma Daqin, who has been under de facto house arrest since 2012, is to remain in detention.

The influential bishop, who defied the government in July 2011 when he became the first bishop to publicly quit the state-backed Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, should continue his “repentance and reflection,” officials told clergymen and nuns attending a “learning” class last week in Shanghai. Shanghai diocese suspended Bishop Ma’s priesthood ministry for a period of two years, leading his followers to believe he may be released soon.

“Government officials said explicitly in the last class that Bishop Ma has to continue his repentance and reflection,” a source at the class told ucanews.com. “So this means that he is not coming out to lead the diocese.” Now being held for a third year, the classes are jointly organized by the local diocese, the Communist Party’s United Front Work Department and the Religious Affairs Committee of Shanghai.

The premise of the classes is to “enhance [the] national, legal and civil awareness” of nuns and clergy who, through their evangelization work, are in touch with many social groups. A diocese notice also claims the classes are aimed at assisting with “a correct understanding” on the independent Church’s relationship with China and patriotism. The notice also instructed attendees to “arrange their work ahead, be punctual and not to take leave”.

Fr. Joseph Fu Hsing-chih went to the Lord

Fr. Joseph Fu Hsing-chih went peacefully to the Lord on May 25, 2014 at the Infirmary in Taipei at 5:45 a.m.

Fr. Fu was born in Donglü, Qingyuan County, Hebei, on Sep. 29, 1924. He entered the Society in Xianxian, on Aug. 14, 1945, was ordained to the priesthood on Mar. 18,

1957 in Baguio, Philippines, and made the last vows on Aug. 15, 1959 at the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church, Kuanhsi, Taiwan.

America’s First Mass

When and where was the first Mass offered in America? No one living today knows the answer to this intriguing question. But we can summarize what we do know about the first Masses in various parts of the New World.

Some legendary accounts of the life of St. Brendan, who was a priest, say he set off in a small boat on a journey to the Isle of the Blessed, sometime around A.D. 512, along with 14 monks and priests. After they landed on Saint Brendan’s Island-wherever that was-he celebrated Mass. There are people who say that elements of the legends of the journey demonstrate that the Irish did have some knowledge of the northeast Atlantic coast of America, so if St. Brendan or some other Irish seafaring priest did arrive there, he would certainly have offered Mass, as he is said to have done in nearly every other place he visited (including, as the legend goes, on the top of a whale in mid-ocean).

Remains of a Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the island of Newfoundland, were discovered and excavated in the 1960s. The settlement dates from around A.D. 1000. It was probably not the only settlement the Norse set up in the region, and it was likely that it served as a sort of permanent outpost for shipping lumber and furs to Greenland and perhaps further east. The size and number of buildings suggest that as many as 150 people lived there.

Icelandic bishop Eric Gnupsson, who had been based in Greenland since 1112, “went to seek Vinland” in 1121-presumably to minister to some of his far-flung Catholic flock-but nothing more was reported of him. If he succeeded, he surely offered the first Mass in the New World, perhaps at L’Anse aux Meadows or at another Norse settlement. With the approval of the Norwegian king, a bishop for Greenland was set up and the see was established in the settlement of Garðar. The first bishop, Arnaldur (Gnupsson’s immediate successor in Greenland), arrived there in 1126 and began construction of a cathedral, devoted to St. Nicholas, the same year. The last bishop served until 1378. Archaeologists have excavated the ruins of the cathedral, a cross-shaped church built of sandstone.

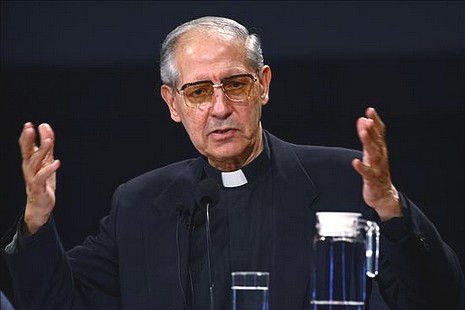

Superior General announces intention to retire

Father Adolfo Nicolás SJ, who has been Superior General of the Jesuits (the Society of Jesus) since 2008, has announced his intention to resign. Having recently reached the age of 78, Fr Nicolás says he has received the approval of his advisers (Assistants) and has informed Pope Francis that he intends to convoke a General Congregation for the latter part of 2016. That will be occasion when his resignation will be formally submitted and his successor will be elected.

In a letter to the entire Society of Jesus, dated 20 May 2014, Fr Nicolás wrote: “Reflecting on the coming years, I have reached the personal conviction that I should take the needed steps towards submitting my resignation to a General Congregation.” He continued that he would therefore convoke the 36th General Congregation towards the end of this year, with a view to it taking place during the final months of 2016.

Fr Nicolás recently visited the Jesuits of Guyana – a Region of the British Province – when he was en route to Mexico (read more). He is due in London next month when he will attend part of the celebrations to mark the 400th anniversary of the founding of Heythrop College, University of London.

Adolfo Nicolás was born in Villamuriel de Cerrato, Palencia, Spain, on 29 April 1936 and entered the Jesuit novitiate of Aranjuez in 1953. He studied at the University of Alcalá, where he earned his licentiate in philosophy. In 1960, he was assigned to Japan where he studied theology at Sophia University in Tokyo. He was ordained to the priesthood on 17 March 1967.

From 1968 to 1971, Fr Nicolás studied at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, from where he earned a doctorate in theology. Upon his return to Japan, he was made professor of systematic theology at Sophia University, teaching there for the next 30 years.

Fr Nicolás was appointed Director of the East Asian Pastoral Institute at the Ateneo de Manila University in Quezon City, Philippines, in 1978 – a post he held for six years. He then went on to serve as rector of the theologate in Tokyo before being appointed as the Jesuit Provincial of Japan. Following his term of office as Provincial, Fr Nicolás remained in Japan, doing pastoral work among poor immigrants in Tokyo.

In 2004, Fr Nicolás returned to the Philippines after he was appointed President of the Jesuit Conference of Provincials for Eastern Asia and Oceania. A native Spanish speaker, Fr Nicolás is also fluent in Catalan, English, Italian, French, and Japanese. He was elected Superior General of the Society of Jesus at its 35th General Congregation in Rome on 19 January 2008.

The Witness of the Bread

|

“He was made known to them in the breaking of bread” (Acts 2:33)

There is a richness to the story of the disciples on the road to Emmaus that makes it difficult to consume it in its entirety or to exhaust its sustenance. Even seemingly minor details nourish the reader in surprising ways. Emmaus itself, the village to which Cleopas and the unnamed disciple are journeying, appears elsewhere in the Bible in 1 Mc 3:40. It seems to bear little connection to Luke’s notice of the city, but there are intriguing links.

Emmaus was the site of Judah Maccabee’s great victory over the Seleucid general Lysias and the army of Antiochus Epiphanes in 166 B.C. Judah’s army “marched out and encamped to the south of Emmaus” (1 Mc 3:57), and against great odds the Maccabees prevailed over the Seleucid army. The goal was to purify and restore the Temple, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of Hanukkah, but the means by which this would be accomplished was military battle. At stake was the freedom to live and worship as Jews. Prior to the battle Judah says, “And now, let us cry to Heaven, to see whether he will favor us and remember his covenant with our ancestors and crush this army before us today. Then all the Gentiles will know that there is one who redeems and saves Israel” (1 Mc 4:10-11).

Judah’s hope was that the Gentiles would come to know that it was God who gave Israel victory, that it was God who was Israel’s redeemer. A variant of the Greek verb for “redeem” used by Judah is used by Cleopas as he walks in sadness toward that same village of Emmaus, the site of one of Israel’s greatest military victories. He speaks to the stranger beside him (Jesus), telling him, “We had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel.”

Is Luke telling us, by using the same Greek word, why Cleopas and the other disciples had such a hard time comprehending Jesus’ crucifixion? Compared to Judah’s crushing military victory, which was proof that “there is one who redeems and saves Israel,” did not Jesus’ mission, which ended on the cross, appear to be an abject failure?

It is here that the radical witness of Jesus and the church would be shaped: God’s redemption would be like nothing they had imagined. It would be made known along the road to Emmaus but in a way that renounced the weapons of war and embraced the food of hospitality. The recognition of the risen Jesus, mysteriously hidden to Cleopas and the unnamed disciple, occurred “when he was at the table with them” and when “he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him.”

But it must be said that even though Cleopas and his companion did not initially recognize Jesus and were immersed in hopelessness, they still invited the stranger to eat with them, to share their table. It was this act of simple hospitality that led to the breaking of the bread and the opening of their spiritual eyes. Jesus was with them; the victory had been the resurrection.

The breaking of the bread takes us both backward into the life of Jesus and forward into the life of the church. For the Emmaus story uses the same language as the story in Luke of the feeding of the 5,000: “Taking the five loaves and the two fish, he looked up to heaven, and blessed and broke them, and gave them to the disciples to set before the crowd” (9:16-17). This miracle certainly points toward the eucharistic celebration, but we ought not to ignore the basic acts of hospitality and physical feeding by which and through which spiritual nourishment can take place.

And so the breaking of the bread on the road to Emmaus also points forward to the need for hospitality in the life of the church, the means by which Jesus is seen in the face of the stranger and the spiritual nourishment of community, through which we share the Eucharist, the body and blood of Christ. Because Jesus had been raised, the church dedicated itself “to the breaking of bread” (Acts 2:42, 46), in which hospitality and spiritual nourishment are combined to make clear that he is the one through whom redemption has come.

John W. Martens is an associate professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minn. Follow him @BibleJunkies.

Looking through the lens of faith

Just when the burden of administrative work was slowly choking the life out of me, when sinking deeper into the teaching ministry seemed to me a nightmare, I attended the Workshop on Ignatian School Leadership (WISL) International. I was one of 31 leaders and administrators of Jesuit schools in Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Timor Leste and Cambodia at the workshop, which was focused on Administrative Leadership: Ignatian Discernment and Decision-Making.

Being invited brought me much excitement, remembering how meaningful my last experience was. However, I went to the WISL extremely tired. My job as Assistant Principal demanded so much from me that I was neglecting my responsibilities as a wife and mother. I was running on empty. Looming on the horizon were bigger responsibilities. Resigning seemed the best choice, because it was the easiest.

Talking about the Examen: (L to R) Fr Stephen Chow SJ (Hong Kong), Fr Christopher Gleeson SJ (Australia) and Fr Plinio Martins SJ (Timor Leste)

Talking about the Examen: (L to R) Fr Stephen Chow SJ (Hong Kong), Fr Christopher Gleeson SJ (Australia) and Fr Plinio Martins SJ (Timor Leste)

I learned through this year’s WISL though that the Ignatian paradigm demands we filter our life experiences through the lens of faith, as our facilitator, Fr Johnny Go SJ, so articulately described. Decision-making in the Ignatian sense does not mean finding the easier, more convenient way out. Ignatian decision-making involves a constant discernment where we “invite God, who cares deeply about what we do, into the decision-making process” and, through this, we “find the freedom to make the best choice”. Thus, as an Ignatian educator, I am invited not only to make good, nuanced, and well thought-out decisions, I am invited to make discerned decisions where I am not the only one deciding but where I allow God to decide with me. Here, learning to “let go and let God” is a requirement. And we all know how difficult that is.

Ignatian discernment is only possible if we embrace what St Ignatius of Loyola called a leadership of reflection and action. The many times I felt lost at work were when I focused too much on the “action” at the expense of the “reflection”. Since work never really stops, then I rationalize that I cannot stop to pray. Surely, I get more things done, but I fail to see how I sacrifice a very important part of my work: understanding who I am and what I hold dear, and how what I do should be consistent to God’s call for me to be the best person I can be. It is only during times when I am “forced” to be quiet and reflect – like during the WISL – that I realize the price I have to pay for this sacrifice: I begin to see my job as “work”, and not anymore as a vocation that God has personally called me to.

During the workshop, one of the most significant prayer experiences I had was when I contemplated Jesus Christ in front of me. I was looking at him as he carried his cross. He too was looking at me. What struck me was how his look was the gaze of a lover towards his beloved – yes, even while burdened by his cross. He never complained; he just contemplated me with much love. I realized then and there that he was calling me to do the same: carry my own cross, but to do it with much love. It is the love for what I have been called to do and the love for the God who has called me that will allow me to become, as the song goes, “his heart today”.

It is also encouraging to know that I am not in this alone. I was with 30 other participants but I am sure they only represent the thousands in the world working for Jesuit educational institutions who are constantly invited to create space for God in their own workplace. Through their sharing, I was reassured by companionship and support – both indispensable for this ministry – and given a reality check that, in spite of the challenges, grace is still present. Who am I to grumble about whining parents, for example, when many of my colleagues from other countries fear for their lives when report cards are given out? Even through them, I hear the Spirit telling me: there is much grace in your life already; you only have to seek it out.

The grace of the WISL for me was to see how my job would always seem like work if not seen through the lens of faith. If I do not see it as a vocation, a call to love, I cannot and will not find meaning in it. As an Ignatian leader, I cannot go on with my role without pausing for reflection and prayer. I harvest the fruits of the WISL now as I have been appointed to a bigger, more demanding role at school. Resigning is still the easiest option, but the more convenient choice is not necessarily the best one from the Ignatian viewpoint. The best option is that which is the most loving, the most life giving, the one that will draw me and others closer to His heart – even if it entails carrying our own cross. Personally, the best option is for me to try to do my best in my new role, knowing I am still, and primarily, a mother and wife at home. The WISL has helped me put things in the proper perspective – proper because it is not only mine, but God’s as well.

The Workshop on Ignatian School Leadership was held in Tagaytay City, Philippines, from March 10 to 14, 2014.