Podcast : A Jesuit in Guantánamo

Luke Hansen, S.J., reports on his visit to Guantánamo Bay, where he witnessed the opening motions in the trial against Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other defendants charged in connection with attacks of 9/11. Luke blogged on his visit here, and you can find his photos on our Facebook page.

|

|

| Download MP3 |

Avoid Jargon

|

by Jim Manney

Here’s timely advice for Ignatian “insiders” from Fr. Alolfo Nicolás, SJ, superior general of the Jesuits. Avoid jargon. Speak clearly and simply. He uses the word “discernment” as an example. You might know what it means, but the people you’re talking to might not. Fr. Nicolás tells some good stories in this video, from a conference about Jesuit partnership with lay people. (Click here to watch it on YouTube.)

Fr General on New Evangelisation

|

In his invention at the 25th Synod of Bishops, Fr General Adolfo Nicolás, superior general of the Society of Jesus, told the Synod that “a New Evangelisation has to learn something from the First Evangelisation, from the things we did well and from the mistakes we committed as well as the insufficiencies we suffered in our desire to communicate the Gospel”.

Stressing that that he was formed in a tradition that encourages finding God in all things, he said “God is present and active in every human community, even if we do not readily see the how or the depth of this presence.”

But, he added, “I am afraid that we, missionaries, have not done it with sufficient depth.”

Fr Nicolás, who spent most of his priesthood in Japan and in other parts of Asia, said that the Church has seen mostly Western, European signs of Faith and Sanctity. “We have not entered with sufficient depth into the cultures where the Gospel was proclaimed in order to see that part of the Kingdom of God that was already there, rooted and active in the hearts and relationships of people. We have not been very willing to find the “surprise factor” in the work of the Holy Spirit, who makes the seed grow even while the farmer is asleep or the missionary is absent.”

He added: “By not paying sufficient attention to how God was present and had been working in the peoples we encountered, we missed important clues, insights and discoveries.”

“The fullness of Christ needs the contribution of all peoples and all cultures,” he said before listing some lessons we can learn from the past that can be of great help in any New Evangelisation. One of these is that “the most credible message is the one that comes from our life, totally taken and guided by the Gospel of Jesus Christ”.

In some reflections on the Synod of Bishops published in the Jesuit Curia website, Fr Nicolás said “The reality around us has become much more complex than we can face individually, and the original challenge of our Mission to serve souls and the Church continues and grows in poignancy. It is my hope that Jesuits will respond to the new challenges with the depth that comes from our appropriation of Ignatian spirituality and from a serious study of our times.”

Asked for signs of what he would consider “Asian” holiness, Fr General replied, “filial piety, that at times reaches heroic levels; the totally centred quest for the Absolute and the great respect for those involved in the quest; compassion as a way of life, out of a deep awareness of human brokenness and fragility; detachment and renunciation; tolerance, generosity to and acceptance of others, open-mindedness; reverence, courtesy, attention to the needs of others; etc.

“Summing up, maybe we can say that if our eyes were open to what God is doing in people (and peoples!) we would be able to see much more Holiness around us and many of us would feel challenged to live the Life of God in new ways that might be more adapted to the way we really are, or the way God wants us to be.”

To read the full text of Fr General’s intervention, click here.

To read Fr General’s reflections on the Synod of Bishops on the Jesuit Curia website, click here.

Blessed Michael Augustine Pro

Born on January 13, 1891 in Guadalupe, Mexico, Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez was the eldest son of Miguel Pro and Josefa Juarez.

Miguelito, as his doting family called him, was, from an early age, intensely spiritual and equally intense in his mischievousness, frequently exasperating his family with his humor and practical jokes. As a child, he had a daring precociouness that sometimes went too far, tossing him into near-death accidents and illnesses. On regaining consciousness after one of these episodes, young Miguel opened his eyes and blurted out to his frantic parents, “I want some cocol” (a colloquial term for his favorite sweet bread). “Cocol” became his nickname, which he would later adopt as a code name during this clandestine ministry.

He studied in Mexico until 1914, when a tidal wave of anti-Catholicism crashed down upon Mexico, forcing the novitiate to disband and flee to the United States, where Miguel and his brother seminarians treked through Texas and New Mexico before arriving at the Jesuit house in Los Gatos, California.

The churches were closed and priests went into hiding. Miguel spent the rest of his life in asecret ministry to the sturdy Mexican Catholics. In addition to fulfilling their spiritual needs, he also carried out the works of mercy by assisting the poor in Mexico City with their temporal needs. He adopted many interesting disguises in carrying out his secretmininstry. He would come in the middle of the night dressed as a beggar to baptize infants, bless marriages and celebrate Mass.

Falsely accused in the bombing attempt on a former Mexican president, Miguel became a wanted man. Betrayed to the police, he was sentenced to death without the benefit of any legal process.

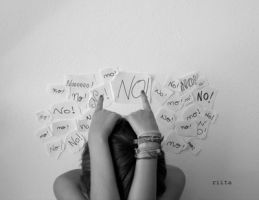

What If the Answer Is No?

by Becky Eldredge

What if God’s answer to one of our prayers is “no”? We are given this answer at times. Sometimes when we are told “no” we easily accept the answer we are given, because what we are asking for is something that really did not matter that much. Occasionally, though, we find ourselves being told “no” when every part of our being wants the answer to be “yes.” What happens to our relationship with God then? Does our relationship with God completely fall apart? Does our entire relationship with God depend on God answering our prayers?

Jesus did not get the “yes” he begged for with every part of his being: “Let this cup pass away from me” (Matthew 26:39). Jesus knew, though, that his prayer was heard, he knew God could answer his prayer, and he knew his Father would be there with him no matter what. Jesus’ relationship with God the Father did not fall apart when his prayer was not answered, because his relationship with God did not depend on answered prayers.

We are invited into a similar relationship-a relationship with God that trusts that our prayers are heard yet does not demand our prayers be answered. We are invited into a relationship of confidence that God can answer our prayers, yet at the same time, we are invited into a relationship that asks us for complete surrender to God’s way. The relationship we are invited into with God is not an insurance policy that guarantees we get what we want. However, we are promised that God hears us and will be with us every step of the way.

I know many of us seek certain things “to pass away from us” in our own lives or in the lives of those we love. When we get an answer of “no” to a prayer we fervently prayed, may we continue to turn to Jesus to help us surrender to God’s will, and may we have the courage to let God take us deeper.

Saints on the Screen

by James Martin, S.J.

The Top Ten Movies about Saints, Blesseds, Venerables, Servants of God and Other Holy Men and Women

Rare is the saint’s biographer who can avoid these words in the first few pages of the book: “His life would make a great film!” Or “Her story was like something out of a Hollywood movie!”

Some lives of the saints seem tailored for the cinema, so inherently visual are their stories. The series of brightly colored frescoes in the Basilica of St. Francis, in Assisi, by Giotto, could be a storyboard pitch for a movie: Francis and his vision at San Damiano, Francis preaching to the birds, and so on. In his book A Brief History of the Saints, Lawrence S. Cunningham notes that there have been, since the talkies, over 30 versions of the life of St. Joan of Arc. Again, one can identify the visual elements with ease: her visions, her meeting the Dauphin, her military conquests, her martyrdom.

The lives of other saints, especially founders of religious orders, are more difficult to dramatize, since they often move from dramatic conversion to undramatic administration. It was long rumored that Antonio Banderas (the cousin of a Jesuit) was set to play St. Ignatius of Loyola on screen. But any marketable screenplay would end after the founding of the Society of Jesus. Few moviegoers would want to slog through an hour of Ignatius sitting at his desk composing the Constitutions or writing one of the 6,813 letters he wrote during his lifetime.

In our time, some saints and near-saints had a closer relationship to their film biographies. In 1997, Mother Teresa approved a script by Dominique LaPierre based on her life, which would star Geraldine Chaplin. “Bless him and his film,” she said. On the other hand, when Don Ameche approached the Abbey of Gethsemani in 1949 to obtain the rights to Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, the abbot, Dom James Fox, said no. (For his part, Merton had been thinking along the lines of Gary Cooper.) After turning down the actor, Dom James asked Mr. Ameche if he had made his Easter duty that year. (He had.)

Films can be a fine introduction to the saints. And sometimes the movie versions are as good as any biography for conveying the saint’s special charism. Here is a roster of the ten best films and documentaries about holy men and women, listed in order of their release.

1.The Song of Bernadette (1943). Busloads of Catholic schoolchildren were taken by enthusiastic priests, sisters and brothers to see this movie upon its release. Since then, the story of the Virgin Mary appearing to a poor girl in a backwater town in Southern France in 1858 has lost little appeal. Based on the novel by Franz Werfel, the movie is unabashedly romantic, with a luminous Jennifer Jones as St. Bernadette Soubirous and the handsome Charles Bickford as her initially doubtful but ultimately supportive pastor, Abbé Peyramale. Some find the score overripe, the dialogue saccharine and the acting hammy (Vincent Price all but devours the French scenery), but the stalwart character of Bernadette comes through. So does the shock that greeted what initially appeared to be a little girl’s lie. (In reality, Bernadette’s parents beat her after hearing their daughter’s tale.) “The Song of Bernadette” effectively conveys Bernadette’s courage in the face of detractors and her refusal to deny her experiences, despite everyone else’s doubts.

2.Joan of Arc (1948). Cinéastes may still sigh over “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” the 1928 silent film starring Maria Falconetti and directed by Carl Theodore Dreyer, but this Technicolor sound version is unmatched for its colorful flair. At 33, Ingrid Bergman was far too old to play the 14-year-old girl, and too statuesque to portray the more diminutive visionary, but the movie makes up for those shortcomings with the intensity of Bergman’s performance and the director Victor Fleming’s love of sheer pageantry. Watch it also for the foppish portrayal of the Dauphin, and later, Charles VII, by José Ferrer. You can tell that he’s going to be a bad king.

3.A Man for All Seasons (1966). It is hard to go wrong with a screenplay by Robert Bolt (who also penned “Lawrence of Arabia” and, later, “The Mission”); Paul Scofield as Sir Thomas, Orson Welles as Cardinal Wolsey; Wendy Hiller as his wife, Alice; and Robert Shaw as an increasingly petulant and finally enraged Henry VIII. Here is a portrait of the discerning saint, able both to find nuance in his faith and see when nuance needs to give way to an unambiguous response to injustice. The movie may make viewers wonders whether St. Thomas More was as articulate as his portrayal in Bolt’s screenplay. He was, and more, as able to toss off an epigram to a group of lords as he was to banter with his executioner before his martyrdom. Read Thomas More, by Richard Marius or The Life of Thomas More, by Peter Ackroyd, for further proof.

4.Roses in December (1982). During a time when the fight for social justice and the “preferential option for the poor” is often derided as passé, this movie reminds us why so many Christians are gripped with a passion to serve the poor, as well as the lasting value of liberation theology. The bare-bones documentary is a moving testament to the witness of three sisters and a lay volunteer who were killed as a result of their work with the poor in Nicaragua in December of 1980. “Roses” focuses primarily on Jean Donovan, the Maryknoll lay missioner, chronicling her journey from an affluent childhood in Connecticut to her work with the poor in Latin America. The film’s simplicity is an artful counterpoint to the simple lifestyle of its subjects and the simple beauty of their sacrifice.

5.Merton: A Film Biography (1984). I’m too biased to be subjective about this short documentary about Thomas Merton, produced by Paul Wilkes, the Catholic writer. Almost 20 years ago, I happened to see this film on PBS and it started me on the road to the priesthood. Last year, I had the opportunity to watch it again and found it equally as compelling. A low-key introduction to the Trappist monk and one of the most influential American Catholics told with still photographs and interviews with those who knew Merton before and after he entered the monastery. The best part of this film is that by the end you will want to read The Seven Storey Mountain, and who knows where that will lead you?

6.Thérèse (1986). This austere work is a rare example of a story about the contemplative life that finds meaningful expression on screen. Alain Cavalier, a French director, deploys a series of vignettes that leads the viewer through the life of Thérèse Martin, from her cossetted childhood until her painful death. It doesn’t quail from showing how difficult life was for Thérèse in the convent at Lisieux, nor the physical pain that attended her last years. But it also shows the quiet joy that attends the contemplative life. A masterpiece of understatement, “Thérèse,” in French with subtitles, reminds us that real holiness is not showy, and the Carmelite nun’s “Little Way” of loving God by doing small things, is made clear to us through this gem of a movie.

7.Romero (1989). One of the great strengths of this movie about the martyred archbishop of San Salvador is its depiction of a conversion. Archbishop Oscar Romero moves from a bishop willing to kowtow to the wealthy to a man converted-by the death of friends, the plight of the poor and his reappropriation of the Gospel-into a prophet for the oppressed. Raul Julia invests the archbishop of San Salvador with a fierce love for the people of his archdiocese that manifests itself in his work for social justice. The actor said that he underwent of a conversion himself while making the film, something that informs his performance. One scene, where Romero wrestles with God-half aloud, half silently-is one of the more realistic portrayals of prayer committed to film.

8.Blackrobe (1991). Admittedly, Bruce Beresford’s film is not about a particular saint. Nevertheless, it hews closely to the lives of several 17th-century Jesuit martyrs, including St. Jean de Brébeuf and St. Isaac Jogues, who worked among the Hurons and Iroquois in the New World. (The protagonist, who meets St. Isaac in the film, is named “Father Laforgue.”). Some Catholics find this movie, based on the stark novel by Brian Moore, who also wrote the screenplay, unpleasant for its bleak portrayal of the life of the priest as well as for its implicit critique that the missionaries brought only misfortune to the Indians. But, in the end, the movie offers a man who strives to bring God to the people that he ends up loving deeply. The final depiction of the answer to the question, “Blackrobe, do you love us?” is an attempt to sum up an entire Catholic tradition of missionary work.

9.St. Anthony: Miracle Worker of Padua (2003). In Italian with subtitles, this is the first feature-length film about the twelfth-century saint best known for helping you find your keys. Hoping to become a knight in his native Lisbon, Anthony is a headstrong youth who almost murders his best friend in a duel. As penance, Anthony makes a vow to become a monk. He enters the Augustinian canons but is soon caught up with the lure of Francis of Assisi, who accepts him into his Order of Friars Minor. The movie successfully conveys the saint’s conversion, the appeal of the simple life and the miraculous deeds reported in his lifetime. The only drawback is that, if medieval portraiture is to be believed, the film’s Anthony looks more like Francis of Assisi than the fellow who plays Francis of Assisi

10.The Saint of 9/11 (2006). You may know Mychal Judge, O.F.M., as one of the more well known heroes of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Father Judge, a beloved fire chaplain in New York City, was killed on Sept. 11, 2001, while ministering to the firefighters in the north tower. What you may not know is that the Franciscan priest was also a longtime servant of the poor and the homeless in New York City, an early minister to AIDS victims when many others (even doctors and nurses) shunned them, and an experienced pastor at three parishes. This remarkable new documentary is a clear-eyed look at Father Judge’s life, showing how his faith enabled him to deal with his alcoholism (through Alcholics Anonymous) and accept his homosexuality (he was a celibate priest), reminding us that sanctity always makes its home in humanity. An Irish Mercy sister, who knew him during a sabbatical in Ireland says simply, “He was a good man who loved so many.” It is the best movie about the priesthood in years. And, in a nod to the first movie on the list, the film notes that besides his devotion to the homeless, to the sick and to his beloved firefighters, the Franciscan priest Judge enjoyed another devotion: to Our Lady of Lourdes and to St. Bernadette.

Kino Border Initiative Receives Binational Collaboration Award

Jesuit Father JBoy Gonzales (right) passes a plate at KBI’s Aid Center for Deported Migrants.

The Kino Border Initiative (KBI), a Jesuit, binational ministry in Nogales, Ariz., and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, was recently honored for its work with migrants. “There’s a lot of negative press about the U.S.-Mexico border, and I think these awards draw attention to positive programs and efforts that are happening on the border and to the people who live and work there,” says Jesuit Father Sean Carroll, executive director of KBI. “It’s a real affirmation of our staff and the work we’re doing.”

The KBI was one of four organizations to receive an award for binational cooperation and innovation along the U.S.-Mexico border from the Border Research Partnership, comprised of Arizona State University’s North American Center for Transborder Studies, the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center and Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana.

The awards program honors “success stories” in local and state collaboration between the United States and Mexico. KBI, the only religious work among those honored, was founded in 2009 by six organizations: the California Province of the Society of Jesus, the Mexican Province of the Society of Jesus, Jesuit Refugee Service/USA, the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist, the Diocese of Tucson and the Archdiocese of Hermosillo.

Currently, there are four Jesuits working at KBI – two from the California Province and two from the Mexican Province. Jesuits are involved in other ways as well. For instance, this summer, a group of seven Jesuits spent five weeks traveling along the Migration Corridor in Central America to experience the route typically traveled by migrants seeking a better life in the United States. KBI was the last stop on their journey. Fr. Carroll says visiting KBI and meeting the migrants can be the most effective type of education.

“We can show photos, we can talk about it, we engage people on the issues – all that’s very helpful. At the same time, when a person or a group is able to dialogue with a group of migrants, that has the biggest impact,” says Fr. Carroll. “The group no longer has just a theoretical idea of the issue, but they think about it in terms of this person or this group of people that has been so affected by the current immigration policy, and I think it has a very significant impact.”

In addition to education and advocacy, KBI also focuses on humanitarian assistance. Since its founding the group has provided thousands of migrants food, shelter, first aid and pastoral support. From the beginning of the year to the end of July, KBI served nearly 36,000 meals to migrants. Last year KBI provided over 450 women and children temporary shelter, and KBI’s clinic treats about 12 to 15 people a day.

“It’s a great blessing for us to offer those services,” Fr. Carroll says. “Our work is very transformative for us individually and as an organization because we serve them and we hear their stories and accompany them at a very difficult time.”

Visit the Kino Border Initiative website, where you can learn more about volunteer and educational opportunities. For more from Fr. Carroll, watch this Ignatian News Network video.

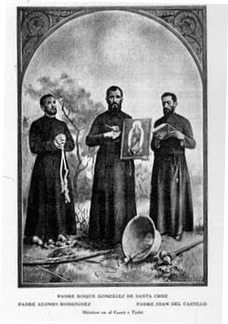

Sts Alfonsus Rodriguez, Roch Gonzalez and St John Del Castillo, SJ

Saints Roch Gonzalez, Alfonsus Rodriguez and John del Castillo, the three martyrs of River Plate were called from their own country to sow the seed of God’s word in distant lands. All three died a martyr’s death in the Jesuit reductions in South America. They were canonized by Pope John Paul II on May 16, 1988.

St Roch Gonzalez was born in Paraquay’s capital city of Asuncion, a descendant of early Spanish colonists. He was ordained a priest in 1599 and was very successful in evangelizing the Indians near Asuncion. And it was rumoured that the bishop, who was then residing in Buenos Aires, was planning to make him his vicar general, John avoided this appointment by entering the Society to become a Jesuit.

Fr Gonzalez was very successful in baptizing the Guaycuru, and at the same time pacified and made them civilized. He taught them how to plough, sow and tend the land, and harvest crops. He was likewise very successful in the reduction of St Ignatius and the settlement also flourished. After four years in St Ignatius he spent the next twelve years in missionary activity devoted to the founding of a series of reductions in today’s Brazil, Paraquay, Uraquay and north eastern Argentina. In 1615, he began establishing settlements and also set about constructing houses and a chapel. This became Itapua, or Our Lady of the Incarnation. He succeeded as a missionary because he was multi-talented: while being pastor of souls, he was likewise architect and mason, farmer and physician. He was also the first Jesuit to enter Uruguay where he founded the town of Concepcion in honor of Our Lady’s Immaculate Conception.

St Alfonsus Rodriguez was born in Zamora, Spain. He entered the Jesuit novitiate at Villagarcia in 1614 and two years later was assigned to the Spanish mission in America. He arrived at Buenos Aries and studied philosophy and theology in Cordoba prior to ordination in 1624. His companion from Spain was Fr John del Castillo. Fr Gonzalez met Fr Rodriguez in Itapua in 1628 when the young missionary asked to accompany Fr Rodriguez on his next assignment to Caaro.

St John del Castillo was born in Belmonte (Toledo), Spain, and initially decided on a career in law. He attended the University of Alcala but during his first year, realized that he had a vocation, so he entered the novitiate in Madrid in 1614. In 1616, he was on his way to the South American mission and one of his companions on this journey was Alfonsus Rodriguez. John was ordained in 1625 and was at the reduction (a settlement) of the Incarnation at Itapua in 1628 when Fr Roch Gonsalez visited it. Fr Gonsalez then took him as his associate to Iyui which he named Assumption because it was founded on August 15. Fr Gonsalez left Fr Castillo in charge of the settlement and then went on to found another settlement named All Saints at Caaro with Fr Rodriguez as his companion.

Because the three Jesuits were making noticeable progress amongst the Indians, the local witch-doctor, Nezu seeing that his influence was waning, decided that it would only be by the priests’ death, that he could regain control of his people. Hence he was determined to kill the missionaries on his territory. On the morning of November 15, 628, Fr Rodriguez went to the woods to fell a tree that was to serve as a pole on which to hang the chapel bell. He and several Indians were carrying the tree into the village when Fr Gonsalez emerged from the chapel after having celebrated Mass. Fr Rodriguez then went in to offer his Mass, but before he began, he heard unusual noises and came out to investigate. He did not see his companion’s massacred body near the bell and by the time he could ask, “What’s happening?” two of Nezu’s men attacked him and struck him on the head when he fell to the ground. He was only 30 years old. The attackers then threw both bodies into the church, destroyed the altar, and smashed the chalice before setting everything ablaze.

Fr Castillo was unaware that Frs Rodriguez and Gonsalez at All Saints were murdered by Nezu’s men on November 15 and that he was to be the next victim. On November 17, Nezu’s men entered the reduction of the Assumption and found Fr Castillo reading his breviary. When asked what he was doing, he politely answered that he was praying. The visitors surrounded him, attacked and beat him and forced him to go into the woods where they beat him to death. He was only 32. His body was set on fire and the assassins went to rob his dwelling and the chapel. Fr Castillo’s body was recovered and taken to the reduction of the Immaculate Conception, where it was interred with his fellow martyrs, Frs Gonsalez and Rodriguez.

St. Joseph Pignatelli, SJ

At twelve, Joseph returned with his younger brother, Nicholas, to Saragossa, where they studied at the Jesuit school. By special privilege, they resided in the Jesuit community. Living among the Jesuits convinced Joseph of his vocation, and in 1753, he entered the novitiate at Tarragona, and took his religious vows two years later. Joseph spent the following year at Manresa, doing classical studies, the next three years studying philosophy at Calatayud, and the subsequent four years back at Saragossa, for his theology.

After Joseph was ordained in 1762, he taught grammar to young boys at his old school and assisted in its parish. He taught for four and a half years, visited the local prisons and ministered to condemned convicts about to be executed. This apostolate ended abruptly when in 1767, King Charles III expelled the Jesuits from his kingdom and confiscated their property, making five thousand Jesuits homeless with one royal stroke of the pen.

Fr Pignatelli was made the acting provincial over some 600 exiled Jesuits on board thirteen ships during their three months at sea before arriving at Bonifacio, on the southern tip of Corsica. Later they were taken away to Genoa. After travelling three hundred miles on foot, they arrived at Ferrara, in the Papal States, tired and exhausted, but were welcomed by Fr Pignatelli’s cousin and future cardinal, Msgr Francis Pignatelli.

The princes of Europe were pressuring the Pope to suppress the Society. Although Clement XIII heroically withstood the pressure, his successor, Clement XIV crumbled beneath it and decreed the dissolution of the Society of Jesus. This meant that Fr Pignatelli and 23,000 others were no longer Jesuits and were no longer bound by their vows.

Saddened by this decree, Fr Pignatelli moved to Bologna where he and his brother, Nicholas, also a Jesuit, continued to live the life of a Jesuit, and for the next twenty four years (1773-1797) he kept in contact with his dispersed brethren. Meantime in White Russia (today’s Belarus) the Jesuits survived, because the Russian Czarina, Catherine II did not carry out the suppression. When Fr Pignatelli heard about this, he obtained permission from Pope Pius XI to affiliate with the Russian Jesuit province. Meantime Ferdinand, Duke of Parma also entered into negotiations with White Russia, and in 1793, three Jesuits came to his Duchy to open a house for the Society. Fr Pignatelli associated himself with this group and in 1797, at sixty, he also promised God poverty, chastity and obedience, just as he did in Spain in 1755.

Fr Pignatelli was made Master of novices in 1799 and in 1803, he was appointed provincial of Italy. When the Society was restored in the kingdom of the Two Sicilies, many former Jesuits came to them to be re-admitted, and the Jesuit apostolate became active again.

Fr Pignatelli and the other Jesuits were expelled from Naples when Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte overran the country. They headed for Rome and were welcomed by Pope Pius VII. Within months of their arrival in Rome, the Jesuits set up a novitiate at Orvieto and were teaching in six diocesan seminaries. Fr Pignatelli was already seventy and had been in exile for forty years when he came to Rome. He still cherished the hope that the Society would be restored throughout the world during his lifetime. His health was weakening and during his last two years, he suffered from frequent hemorrhages due to tuberculosis and was soon confined to bed.

Fr Pignatelli died peacefully on November 15, 1811 without seeing the end of the 41-year suppression. However, his dearest hope of seeing the entire Society restored was realized when Pope Pius VII decreed it on August 7, 1814, three years after his death. Society of Jesus” died peacefully and serenely.

Podcast : The Ignatian Way

Roger Haight, S.J., and James Martin, S.J., discuss the genius of the Spiritual Exercises. Both priests have written recent books on the Exercises. Fr. Haight’s book, Christian Spirituality for Seekers, was published this summer. Fr. Martin’s The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything is out in paperback.

|

|

| Download MP3 |