His Way of Proceeding

by James Martin, SJ

How might Jesuit spirituality influence Pope Francis’ papacy?

The weeks following the election of Pope Francis, the first Jesuit elected to that office, saw more people asking questions about Jesuits than at perhaps any other time in the last 25 years. Most readers of America already know what a Jesuit is, but another question bears some reflection: How might Jesuit spirituality influence, and how has it already influenced, our new pope?

Jesuit spirituality is based on the life and teachings of St. Ignatius Loyola, the soldier-turned-mystic who founded the Society of Jesus in 1540. Much of that spirituality flows from his classic text, The Spiritual Exercises, a manual for a four-week retreat inviting a person into imaginative meditations on the life of Christ. The Exercises mean more than simply reading the New Testament. Retreatants are urged to imagine themselves, with as much vividness as possible, in the Gospel scenes. As the spiritual writer Joseph Tetlow, S.J., once wrote, the retreatant is not even observing from a distance but is “standing warm in the Temple or ankle-deep in the water of the Jordan.” Through such intense encounters with the Gospel narratives, the person praying enters into a deep, personal relationship with Jesus.

Each Jesuit “makes” the Exercises at least twice in his life: first as a novice and again, years later, at the end of the formation program during a period of time known as tertianship. Therefore, we know that Pope Francis has done this. Moreover, in the late 1960’s, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, S.J., served as the Jesuit novice director for the Argentine Province, which means that he also guided novices through the Spiritual Exercises. He is therefore deeply familiar with Ignatian spirituality.

Embedded in the Exercises are certain key spiritual themes. Jesuits and all who make the Exercises are invited to be “detached” from whatever would prevent them from following God. We are supposed to be “indifferent,” open toward anything, preferring, in Ignatius’ famous formulation, neither wealth nor poverty, neither health nor sickness, neither a long life nor a short one. It is a tall spiritual order, but a clear goal for Jesuits. Finally, Jesuits are to be disponible, a Spanish word meaning “available,” ready to go wherever God, who works through our superiors, wishes.

This may help explain the surprising accession of Cardinal Bergoglio to the papacy. Many people have wondered: Don’t most Jesuits at the end of their training make promises not to “strive or ambition” for high office in the church and Society of Jesus? In short: Yes. Ignatius was opposed to the clerical careerism that he saw in his day and built into the final vows a safeguard against that kind of climbing. But freedom is also built into Ignatian spirituality. If a Jesuit is asked to do something by the church, he is available. (And to answer a complex question: Yes, technically, Pope Francis is still a Jesuit, according to Canon 705, which states that a religious who is ordained a bishop remains a “member of his institute.”)

Other sources of Ignatian spirituality are found in the saint’s laconic autobiography; the Jesuit Constitutions, written by Ignatius; the lives of the Jesuit saints; and as John W. O’Malley, S.J., points out in his superlative book The First Jesuits, the activities of St. Ignatius and the early Jesuits. As Father O’Malley notes, it is one thing to know that the Jesuits in the 16th century were available enough to take on any kind of ministry that would “help souls,” as Ignatius put it; it is quite another to know that they opened a house for reformed prostitutes in Rome and sent theologians to the Council of Trent.

Some Ignatian Hallmarks

But what are the hallmarks of Ignatian spirituality (the broader term used these days, as a complement to “Jesuit spirituality”), and how might they influence Pope Francis? Let me suggest just a few and point out how we may have already seen them in the first few weeks of his papacy.

First, one of the most popular shorthand phrases to sum up Ignatian spirituality is “finding God in all things.” For Ignatius, God is not confined within the walls of a church. Besides the Mass, the other sacraments and Scripture, God can be found in every moment of the day: in other people, in work, in family life, in nature and in music. This provides Pope Francis with a world-embracing spirituality in which God is met everywhere and in everyone. The pope’s now-famous washing of feet at a juvenile detention center in Rome during the Holy Thursday liturgy underlines this. God is found not only in a church and not only among Catholics, but also in a prison, among non-Catholics and Muslim youth, and among both men and women.

Second, the Jesuit aims to be a “contemplative in action,” a person in a busy world with a listening heart. That quality was evidenced within the first few minutes of this papacy. When Francis stepped onto the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square, he began not with the customary papal blessing but with a request for the prayers of the people. In the midst of a boisterous crowd, he asked for a moment of silent prayer and bowed his head. Offering quiet in the midst of the tumult, he was the contemplative in action.

Third, like members of nearly all religious orders, Jesuits make a vow of poverty. We do this twice in our lives-at first vows and at final vows. We are, said St. Ignatius, to love poverty “as a mother.” There are three reasons adduced for that: first, as an imitation of Jesus, who lived as a poor man; second, to free ourselves from the need for possessions; and third, to be with the poor, whom Christ loved.

But Ignatius noted that Jesuits should not only accept poverty, we should actively choose to be like “the poor Christ.” So far Pope Francis has eschewed many of the traditional trappings of the papacy. Before stepping onto the balcony, he set aside the elaborate mozzetta, the short cape that popes normally wear; since then his vestments have been simple. He elected to live not in the grand Apostolic Palace but in a small, two-room suite in the Casa Santa Marta, where the cardinals had stayed for the conclave. He is, so far, choosing the poorer option. This is not unique to Jesuits (and many of Ignatius’ ideas on poverty were inspired by St. Francis of Assisi, the pope’s namesake), but it is a constitutive part of our spirituality.

Another hallmark is occasionally downplayed in commentaries on Jesuit spirituality: flexibility. But over and over in the Jesuit Constitutions, flexibility is recommended for Jesuit superiors. Remember that Father Bergoglio, before he became archbishop of Buenos Aires, was not only the novice director and director of studies, but also the Jesuit provincial, or regional superior, for the country-three different assignments as a superior. Those roles in governance would all require knowledge of Ignatius’ understanding of flexibility.

While the Constitutions set down exacting rules for Jesuit life, Ignatius recognized the need to meet situations as they arise with creativity. After a lengthy description of precisely what was required in a particular aspect of community life, he would often add a proviso, knowing that unforeseen circumstances call for flexibility. “If something else is expedient for an individual,” he writes about Jesuits studying a particular course, “the superior will consider the matter with prudence and may grant an exemption.” Flexibility is a hallmark of the document, and it seems to be with Francis also, who seems happy to speak off-the-cuff in his homilies and adapt himself to the needs of the situation-like stopping a papal motorcade to embrace a disabled child in the crowd.

Jesus as Friend

Two more observations about Pope Francis’ Ignatian heritage. His homily for the Easter Vigil Mass seemed, at least to me, suffused with Ignatian themes. (But of course this may be my Jesuit bias!) He began by inviting his listeners to place themselves within the story, one of the key techniques of the Exercises. Imagine yourself, he suggested, as one of the women going to the tomb on Easter Sunday. “We can imagine their feelings as they make their way to the tomb, a certain sadness, sorrow that Jesus had left them, he had died, his life had come to an end,” the pope said. “Life would now go on as before. Yet the women continued to feel love, the love for Jesus which now led them to his tomb.”

Later in the homily the pope asked his listeners to consider Jesus as a friend. “Welcome him as a friend, with trust: He is life! If up till now you have kept him at a distance, step forward. He will receive you with open arms.” It was easy to hear echoes of the Spiritual Exercises, in which Ignatius asks us several times to speak to Jesus “as one friend speaks to another.” It is an especially warm way of looking at the Son of God.

It would be wrong to say that knowledge of the pope’s spiritual traditions makes it possible to predict what he will do. But it would be equally wrong to say that we know nothing about his spirituality or that his spirituality will have no influence on his ministry. Like any Jesuit, especially a former novice director and superior, Pope Francis is deeply grounded in the spirituality of St. Ignatius and the Society of Jesus, whose seal he has placed on his papal coat of arms. I look forward to seeing how Ignatian spirituality may help him in his new office.

James Martin, S.J., is editor at large of America and the author of The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything. Portions of this article first appeared in The Tablet of London.

Challenging times for the Myanmar Mission

Mark Raper SJ

Many may have thought the battle won when Aung San Suu Kyi was free to appear in public, when hundreds of political prisoners were released, when dissidents were free to return home from exile abroad, when censorship and sanctions were lifted, when elections were held, and as parliament sits to draft a new constitution. In reality the work of rebuilding Myanmar is just beginning.

After half a century of brutal mismanagement and appalling leadership, myriad resentments simmer. Decades of neglect in education, health care, social welfare, and infrastructure cannot be overcome in an instant. As the dictatorship eases control on its own citizens, people seize the opportunity to protest the injuries and injustices they have suffered. As self-expression becomes more common, powerful ethnic, religious and cultural frameworks are evident, and fanaticism, racial disagreements, and old envies are rehearsed.

The treatment of the Rohingya, the response to the escalating attacks on Muslims in Myanmar, the capacity to achieve a peaceful settlement in the Kachin war, the ability to find harmony among many ethnic and racial groups, will test not only the new Myanmar regime of Thein Sein, but also its newfound friends, the many countries and companies now enjoying a honeymoon of new investment possibilities in the country. In this context, new social restraint, new skills of negotiation, new efforts for building community and for protecting the environment are sorely needed.

The Church in Myanmar is awakening to new opportunities and challenges. With few public services apart from seminaries and kindergartens, and a history of necessary isolation from authorities and other religions, the Church begins to learn to take its place in civil society. Now Church leaders have opportunities to develop friendships and trust, and to negotiate across many sectors of society.

The challenges for the Myanmar Jesuit Mission in this context are also great. It is possibly too early to build institutions, but not too early to invest in people and their formation. Recently the mission hosted a visit by a number of provincials for a consultation on how the universal Society might cooperate with and support the mission. They met with Church and civil society members who outlined developments, challenges and opportunities within Myanmar.

The consultation considered our services to the Church, outreach activities to Myanmar society, and internal issues such as formation and governance. The provincials were encouraging; they understood our goals and needs. The importance of finding qualified personnel, both for long and short term assignments, became clear. Promises were given for financial help, for support to a scholarship fund for our lay collaborators, for study opportunities for Jesuits, and for help in searching for resource persons such as educators, spiritual fathers and teachers in seminaries, and for formators of religious. Given the need to inculturate more deeply and to develop apostolic outreach in Burmese language, those being sent for long term assignments will normally be given time to learn the language. Even those on short term assignments, such as regents who come for two or three years, will have opportunities for language studies.

There are more than 30 Myanmar Jesuits in formation, many of them studying in the Philippines and Indonesia. Quite a number will come home this year for some years of practical immersion in service of their people. The challenging times ahead in Myanmar over the coming decades will require qualities of diverse skills, discernment, discipline and deep self-knowledge not just in them but in all who are committed to building community, capacity in the young and harmony in society.

As Easter breaks open with the new light and hope of dawn, please join in prayer and practical support for the fledgling Myanmar Mission in its service of a country now emerging from a long, dark night of isolation and oppression.

Saints on the Screen

by James Martin, S.J.

The Top Ten Movies about Saints, Blesseds, Venerables, Servants of God and Other Holy Men and Women

Rare is the saint’s biographer who can avoid these words in the first few pages of the book: “His life would make a great film!” Or “Her story was like something out of a Hollywood movie!”

Some lives of the saints seem tailored for the cinema, so inherently visual are their stories. The series of brightly colored frescoes in the Basilica of St. Francis, in Assisi, by Giotto, could be a storyboard pitch for a movie: Francis and his vision at San Damiano, Francis preaching to the birds, and so on. In his book A Brief History of the Saints, Lawrence S. Cunningham notes that there have been, since the talkies, over 30 versions of the life of St. Joan of Arc. Again, one can identify the visual elements with ease: her visions, her meeting the Dauphin, her military conquests, her martyrdom.

The lives of other saints, especially founders of religious orders, are more difficult to dramatize, since they often move from dramatic conversion to undramatic administration. It was long rumored that Antonio Banderas (the cousin of a Jesuit) was set to play St. Ignatius of Loyola on screen. But any marketable screenplay would end after the founding of the Society of Jesus. Few moviegoers would want to slog through an hour of Ignatius sitting at his desk composing the Constitutions or writing one of the 6,813 letters he wrote during his lifetime.

In our time, some saints and near-saints had a closer relationship to their film biographies. In 1997, Mother Teresa approved a script by Dominique LaPierre based on her life, which would star Geraldine Chaplin. “Bless him and his film,” she said. On the other hand, when Don Ameche approached the Abbey of Gethsemani in 1949 to obtain the rights to Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, the abbot, Dom James Fox, said no. (For his part, Merton had been thinking along the lines of Gary Cooper.) After turning down the actor, Dom James asked Mr. Ameche if he had made his Easter duty that year. (He had.)

Films can be a fine introduction to the saints. And sometimes the movie versions are as good as any biography for conveying the saint’s special charism. Here is a roster of the ten best films and documentaries about holy men and women, listed in order of their release.

1.The Song of Bernadette (1943). Busloads of Catholic schoolchildren were taken by enthusiastic priests, sisters and brothers to see this movie upon its release. Since then, the story of the Virgin Mary appearing to a poor girl in a backwater town in Southern France in 1858 has lost little appeal. Based on the novel by Franz Werfel, the movie is unabashedly romantic, with a luminous Jennifer Jones as St. Bernadette Soubirous and the handsome Charles Bickford as her initially doubtful but ultimately supportive pastor, Abbé Peyramale. Some find the score overripe, the dialogue saccharine and the acting hammy (Vincent Price all but devours the French scenery), but the stalwart character of Bernadette comes through. So does the shock that greeted what initially appeared to be a little girl’s lie. (In reality, Bernadette’s parents beat her after hearing their daughter’s tale.) “The Song of Bernadette” effectively conveys Bernadette’s courage in the face of detractors and her refusal to deny her experiences, despite everyone else’s doubts.

2.Joan of Arc (1948). Cinéastes may still sigh over “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” the 1928 silent film starring Maria Falconetti and directed by Carl Theodore Dreyer, but this Technicolor sound version is unmatched for its colorful flair. At 33, Ingrid Bergman was far too old to play the 14-year-old girl, and too statuesque to portray the more diminutive visionary, but the movie makes up for those shortcomings with the intensity of Bergman’s performance and the director Victor Fleming’s love of sheer pageantry. Watch it also for the foppish portrayal of the Dauphin, and later, Charles VII, by José Ferrer. You can tell that he’s going to be a bad king.

3.A Man for All Seasons (1966). It is hard to go wrong with a screenplay by Robert Bolt (who also penned “Lawrence of Arabia” and, later, “The Mission”); Paul Scofield as Sir Thomas, Orson Welles as Cardinal Wolsey; Wendy Hiller as his wife, Alice; and Robert Shaw as an increasingly petulant and finally enraged Henry VIII. Here is a portrait of the discerning saint, able both to find nuance in his faith and see when nuance needs to give way to an unambiguous response to injustice. The movie may make viewers wonders whether St. Thomas More was as articulate as his portrayal in Bolt’s screenplay. He was, and more, as able to toss off an epigram to a group of lords as he was to banter with his executioner before his martyrdom. Read Thomas More, by Richard Marius or The Life of Thomas More, by Peter Ackroyd, for further proof.

4.Roses in December (1982). During a time when the fight for social justice and the “preferential option for the poor” is often derided as passé, this movie reminds us why so many Christians are gripped with a passion to serve the poor, as well as the lasting value of liberation theology. The bare-bones documentary is a moving testament to the witness of three sisters and a lay volunteer who were killed as a result of their work with the poor in Nicaragua in December of 1980. “Roses” focuses primarily on Jean Donovan, the Maryknoll lay missioner, chronicling her journey from an affluent childhood in Connecticut to her work with the poor in Latin America. The film’s simplicity is an artful counterpoint to the simple lifestyle of its subjects and the simple beauty of their sacrifice.

5.Merton: A Film Biography (1984). I’m too biased to be subjective about this short documentary about Thomas Merton, produced by Paul Wilkes, the Catholic writer. Almost 20 years ago, I happened to see this film on PBS and it started me on the road to the priesthood. Last year, I had the opportunity to watch it again and found it equally as compelling. A low-key introduction to the Trappist monk and one of the most influential American Catholics told with still photographs and interviews with those who knew Merton before and after he entered the monastery. The best part of this film is that by the end you will want to read The Seven Storey Mountain, and who knows where that will lead you?

6.Thérèse (1986). This austere work is a rare example of a story about the contemplative life that finds meaningful expression on screen. Alain Cavalier, a French director, deploys a series of vignettes that leads the viewer through the life of Thérèse Martin, from her cossetted childhood until her painful death. It doesn’t quail from showing how difficult life was for Thérèse in the convent at Lisieux, nor the physical pain that attended her last years. But it also shows the quiet joy that attends the contemplative life. A masterpiece of understatement, “Thérèse,” in French with subtitles, reminds us that real holiness is not showy, and the Carmelite nun’s “Little Way” of loving God by doing small things, is made clear to us through this gem of a movie.

7.Romero (1989). One of the great strengths of this movie about the martyred archbishop of San Salvador is its depiction of a conversion. Archbishop Oscar Romero moves from a bishop willing to kowtow to the wealthy to a man converted-by the death of friends, the plight of the poor and his reappropriation of the Gospel-into a prophet for the oppressed. Raul Julia invests the archbishop of San Salvador with a fierce love for the people of his archdiocese that manifests itself in his work for social justice. The actor said that he underwent of a conversion himself while making the film, something that informs his performance. One scene, where Romero wrestles with God-half aloud, half silently-is one of the more realistic portrayals of prayer committed to film.

8.Blackrobe (1991). Admittedly, Bruce Beresford’s film is not about a particular saint. Nevertheless, it hews closely to the lives of several 17th-century Jesuit martyrs, including St. Jean de Brébeuf and St. Isaac Jogues, who worked among the Hurons and Iroquois in the New World. (The protagonist, who meets St. Isaac in the film, is named “Father Laforgue.”). Some Catholics find this movie, based on the stark novel by Brian Moore, who also wrote the screenplay, unpleasant for its bleak portrayal of the life of the priest as well as for its implicit critique that the missionaries brought only misfortune to the Indians. But, in the end, the movie offers a man who strives to bring God to the people that he ends up loving deeply. The final depiction of the answer to the question, “Blackrobe, do you love us?” is an attempt to sum up an entire Catholic tradition of missionary work.

9.St. Anthony: Miracle Worker of Padua (2003). In Italian with subtitles, this is the first feature-length film about the twelfth-century saint best known for helping you find your keys. Hoping to become a knight in his native Lisbon, Anthony is a headstrong youth who almost murders his best friend in a duel. As penance, Anthony makes a vow to become a monk. He enters the Augustinian canons but is soon caught up with the lure of Francis of Assisi, who accepts him into his Order of Friars Minor. The movie successfully conveys the saint’s conversion, the appeal of the simple life and the miraculous deeds reported in his lifetime. The only drawback is that, if medieval portraiture is to be believed, the film’s Anthony looks more like Francis of Assisi than the fellow who plays Francis of Assisi

10.The Saint of 9/11 (2006). You may know Mychal Judge, O.F.M., as one of the more well known heroes of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Father Judge, a beloved fire chaplain in New York City, was killed on Sept. 11, 2001, while ministering to the firefighters in the north tower. What you may not know is that the Franciscan priest was also a longtime servant of the poor and the homeless in New York City, an early minister to AIDS victims when many others (even doctors and nurses) shunned them, and an experienced pastor at three parishes. This remarkable new documentary is a clear-eyed look at Father Judge’s life, showing how his faith enabled him to deal with his alcoholism (through Alcholics Anonymous) and accept his homosexuality (he was a celibate priest), reminding us that sanctity always makes its home in humanity. An Irish Mercy sister, who knew him during a sabbatical in Ireland says simply, “He was a good man who loved so many.” It is the best movie about the priesthood in years. And, in a nod to the first movie on the list, the film notes that besides his devotion to the homeless, to the sick and to his beloved firefighters, the Franciscan priest Judge enjoyed another devotion: to Our Lady of Lourdes and to St. Bernadette.

Best Ignatian Songs: Laughing With

by Jim Manney

Regina Spektor is an indie pop singer-songwriter and pianist with a serious bent. She’s written several songs on biblical themes. In “Laughing With,” she ventures into theology, contrasting the times when we take God seriously with the times we don’t. It helps to follow the lyrics. This video has them in both English and Spanish.

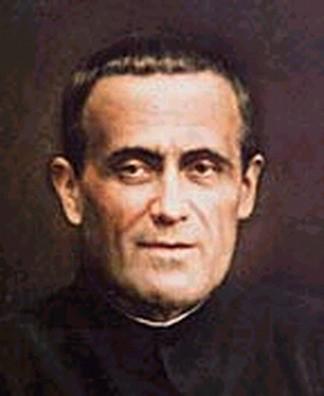

José María Rubio Peralta, S.J. (1864 – 1929)

Fr. José María Rubio Peralta is commonly known as the “Apostle of Madrid.” Born in 1864 in southern Spain, he was drawn as a young man to the thought of becoming a member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuit), but because of personal obligations he was not able to do so until 1906.

By then he was already a diocesan priest with many years of experience working in parishes. For most of his life as a Jesuit – from 1911 until his death in 1929 – he served in Madrid where his simple and sincere sermons touched many people and where he was sought after in the confessional as a compassionate and wise priest. His work, however, was not limited to the church building; he regularly visited Madrid’s slums where he was known as a friend to the city’s destitute and homeless, providing both spiritual and physical aid.

He died of a heart attack at the age of 64 while visiting the Jesuit community in Aranjuez. His remains are buried in Madrid, in the Jesuit church of San Francisco de Borja on Calle Maldonado. In 2003 Pope John Paul II declared him a saint.

Examining the Day and Choosing Freedom

by Joseph Tetlow, SJ

Ignatius suggested several ways to examine the day. If you make this prayer at night, look back over the day to examine what you did or did not do. You could remember by periods, or hour by hour, or one activity at a time. If you make the Examen in the early morning, look back over yesterday and forward into today. Another way to do the Examen is to focus on one act or attitude, one virtue or vice.

The Examen is about choosing freedom. We ask about the characteristic habits that mark or maybe hamper our spiritual freedom. Actions do not harm us spiritually because the commandments forbid them; the commandments forbid them because they harm us. God’s commands are to protect our freedom and even expand it.

The self-examination in this prayer means reclaiming our own freedom. It begins with naming the strengths and gifts that God gives us. Our gifts tell us what God hopes in us. Our lasting freedom lies in living the gifts-each and all of the gifts-that God gives us.

Any idea that the Examen is a self-centered exercise is mistaken. First, because we live in relationships, we cannot know ourselves except in our relationships. And second, because the very gifts we are thanking God for and examining are gifts given not for ourselves alone, but for those whom God gives us to and gives to us.

This is what Jesus meant by “fulfilling” the law: we obey it out of love for God, for our neighbor, and for ourselves.

Fr. Schneider: World’s Oldest Teacher

Fr. Schneider: World’s Oldest Teacher

The Guinness World Records recently recognized Fr. Geoffrey Schneider, a 99-year-old Australian Jesuit, as the world’s oldest active teacher. He teaches religion and serves as chaplain at St. Aloysius College in Sydney. He says that his secret is “a mountain of patience. If things are going wrong, don’t start shouting. Just proceed quietly and things will settle down eventually.”

Joe Koczera, SJ, has more about Fr. Schneider on his blog. Here is a video profile. (Click here to see the video on YouTube.)

Index of Shalom May 2013

- PRAYING WITH THE CHURCH

- The Road to Daybreak – A Spiritual Journey

- 1 May St Joseph the Worker

- 2 May St. Anthanasius, Bishop & Doctor

- 3 May SS Philip & James, Apostles

- 4 May

- 5 May Sunday

- 6 May

- 7 May

- 8 May

- 9 May THE ASCENSION OF THE LORD

- 10 May

- 11 May

- 12 May Sunday

- 13 May Our Lady of Fatima

- 14 May St Matthias, Apostle

- 15 May

- 16 May

- 17 May

- 18 May St John I, Pope & martyr

- 19 May Pentecost Sunday (C)

- 20 May

- 21 May

- 22 May St Rita of Cascia, Religious

- 23 May

- 24 May

- 25 May St Bede the Venerable, Priest & Doctor, St Mary Magdalene de’ Pazzi, virgin

- 26 May The Most Holy Trinity

- 27 May St Augustine of Canterbury, Bishop

- 28 May

- 29 May

- 30 May

- 31 May Visitation of the BV Mary

5th Week of Easter

6th Week of Easter

7th Week of Easter

7th Week in Ordinary Time

8th Week in Ordinary Time

Bishop Jin of Shanghai dead at 96

Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian of Shanghai

by UCAnews

Bishop Aloysius Jin Luxian of Shanghai, a prominent and controversial figure in the Church of China, died on Saturday aged 96 following a long struggle against pancreatic cancer.

His prominence was reflected from the title of his biography Le Pape Jaune (the Yellow Pope), written by French journalist Dorian Malovic in 2006.

“The Vatican thinks that I don’t work enough for the Vatican, and the government thinks that I work too much for the Vatican,” the prelate said in an interview with The Atlantic in 2007. “It is not easy to satisfy both.”

Following his release from detention and return to Shanghai in 1982, Bishop Jin played a leading role in the Church in China, It started with his leading the rebuilding of China’s biggest diocese – Shanghai – where he resumed leadership of the seminary on his return. He was taken into detention in 1955 when he was rector of the diocesan seminary in the city.

He became a figure of significance in Shanghai and on the national stage. He persuaded the authorities to allow inclusion of prayer for the Pope in the Eucharistic Prayers said during Masses and helped to develop the liturgy in Chinese. The Church in China lost contact with the reforms of Vatican Council II during decades of political turmoil.

He was named an honorary president of the national Catholic Patriotic Association and the Chinese Bishops’ Conference at the National Congress of Catholic Representatives held in late 2010.

Though his health had deteriorated since Christmas, his name was among the nine Catholic representatives of the 12th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the top advisory body to the Beijing government.

Bishop Jin was born on June 20, 1916 in Shanghai. His parents died when he was young and, after attending the Jesuits’ high school in Shanghai, he entered the seminary there in 1932. From the local seminary, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1938. He was ordained a priest in 1945 and, after two years of pastoral work, he was sent to Rome to pursue theological studies. He obtained a doctorate in theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome in 1950 and returned to China as the new Communist regime led by Mao Zedong took over the mainland.

From 1951 on, the government arrested and expelled foreign missionaries as the then Father Jin progressively took charge of the Jesuits in Shanghai, later writing that he knew the time would come when the Security Police would take him into custody. He simultaneously became rector of the Shanghai Diocesan Seminary, the Jesuit’s vice-superior in Shanghai and was designated as the Jesuit Visitor for China, with delegated powers of the superior-general in Rome.

He was arrested with hundreds of priests, religious and laity, in the “September 8 Incident” in 1955, a major crackdown against the “counterrevolutionary clique” of Bishop (later cardinal) Ignatius Gong Pinmei of Shanghai.

Jin was sentenced to jail and re-education for three decades during which time – owing to his fluency in four European languages – he became a translator of technical manuals and other documents claimed to be of importance to China’s industrial development. Though still serving his sentence, he worked for a translation company linked to the Public Security Bureau, a connection that aroused the suspicions of some Catholics.

In 1982, he was released and became the founding rector of the diocesan seminary built near the Basilica of Mary, Help of Christians in Sheshan, outside Shanghai. The seminary has trained more than 400 priests and 16 bishops in eastern China.

Jin and Father Stephen Li Side were together ordained coadjutor bishops without papal approval in 1985, and Jin succeeded as the ordinary of Shanghai’s open community in 1988. The Vatican later recognized Bishop Jin as coadjutor bishop of Shanghai in 2004. When Jin became ordinary in 1988, he invited Bishop Li to be a diocesan consultor.

His death leaves open a succession issue in the open community in one of the most important Chinese dioceses. In 2005, he ordained Auxiliary Joseph Xing Wenzhi as his successor but the Shangdong native faded from visibility in late 2011. According to the 2013 Spring Issue of Tripod, published by the Holy Spirit Study Centre in Hong Kong, Bishop Xing resigned on December 20, 2011. It is not clear whether the Vatican has received or accepted his resignation.

The second auxiliary bishop, Thaddeus Ma Daqin, was restricted from episcopal ministry soon after his ordination last July as he publicly announced he would quit the Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA), which advocates an independent Church for China. The government-sanctioned bishops’ conference subsequently revoked his appointment letter as coadjutor bishop.

Though restricted in his movements by the government, Bishop Ma blogs on his Weibo account – the Chinese equivalent of Twitter – almost every day, sharing his thoughts on the scripture for daily Mass. Church sources said he was taken away from the Sheshan Seminary to a “study class” run by government authorities for two months on April 14 because authorities did not want him to meet pilgrims at the nearby Marian Basilica during Our Lady’s month of May.

Bishop Jin was a friend to numerous international political and religious leaders. He was also one of the four Mainland Chinese bishops invited by Pope Benedict XVI to attend the world bishop synod in 2005. None was permitted to leave the country by the government.

Podcast : Homeboy Ministry

Greg Boyle, S.J., is founder of Homeboy Industries, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. He is also the author of Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion, which made the New York times bestseller list. Homeboy industries serves high-risk, formerly gang-involved men and women with free programs like tattoo removal, legal services, and mental health services. It also operates seven social enterprises that serve as job-training sites, including Homeboy Bakery, Homegirl Café and Homeboy silkscreen and embroidery. We spoke with Fr. Greg at the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress in New York after he offered a talk about his work to a large crowd, moving many to tears.

|

|

| Download MP3 |