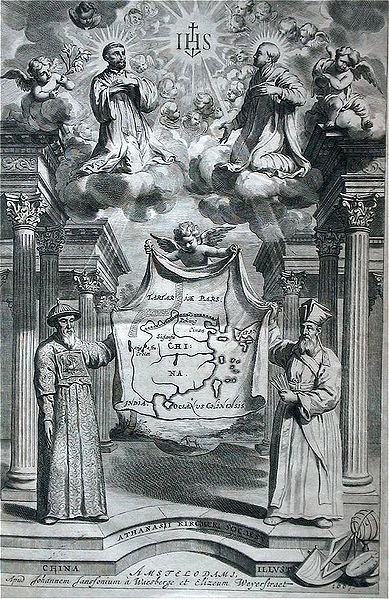

Above: Francis Xavier (left), Ignatius of Loyola (right) and Christ at the upper center. Below: Matteo Ricci (right) and Johann Adam Schall von Bell (left), all in dialogue towards the evangelization of China.

By Paul Mariani, S.J.

Fr. Paul Mariani is Assistant Professor of History at Santa Clara University. His book Church Militant: Bishop Kung and Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai has been recently published by Harvard University Press.

I. Introduction

Since its beginning, the Society of Jesus has had a close connection with China and the Chinese people. Perhaps no Catholic religious order has had such a strong relationship with a particular country as the Society of Jesus has had with China. This should not surprise us. St. Ignatius (1491-1556), founder of the Jesuits, himself wanted Jesuits to be available for worldwide mission. They were to be available for mission to the Turks and to “the region called the Indies” for “the defense and propagation of the faith.” In fact, the zeal with which these early Jesuit missionaries set out was one of the most impressive apostolic ventures in the history of the church. Some have even compared their efforts to a second apostolic era. And of the many places that the early Jesuits evangelized, they would soon prize China as one of their key missions.

In fact, the Jesuits were the third act in Chinese Christian history. The first Christian missionaries to what is today China had come as early as the 7th century. They were the so-called Nestorians, from the Church of the East. The second group was the Franciscans who came to China some 400 years later. They even built the first Catholic Church in Beijing in 1299. Neither of these early Christian communities survived. The third act would. For the Jesuits helped to found a vibrant indigenous church, and thus inaugurated modern Chinese Christian history.

The history of the Jesuit China mission is necessarily a vast subject. My purpose here, in this first of two articles, is simply to trace some of the key developments of the mission from its promising start in 1552, to its unfortunate decline and near destruction by 1800. Further, in order to help guide our path and focus our efforts, I will make use of several recent books, most of them published in the last ten years. Therefore, it is my hope that this essay may serve as a state of the field survey, in order to better acquaint the reader not only with the general contours of this fascinating history, but to highlight the contributions of the latest scholarship as well.

II. Francis Xavier and the Pioneers of the Early Jesuit Mission

It was none other than Francis Xavier (1506-1552), one of the original founders of Jesuits, whom Ignatius sent to be the first Jesuit apostle to “the Indies,” and this even before the Jesuits had received final approval for their new institute. After ten years of work in India, Indonesia, and Japan, Francis Xavier died on the small island of Shangchuan overlooking mainland China. In fact, over the years, St. Francis Xavier himself has come to symbolize some of the unbounded hopes and frustrated desires of the Jesuit China mission. For Francis Xavier never set foot in mainland China, but succeeding groups of Jesuit missionaries would attempt to fulfill his dream.

The story is familiar to many. After arriving in Japan in 1549-only six years after first European contact-Xavier soon learned that the Japanese looked to China as the source of culture, much like early modern Europeans looked to ancient Greece and Rome. Xavier was soon put on the defensive. If Christianity was such a great religion, why had the Chinese failed to mention it? To answer this objection, Xavier resolved to travel to China and even to the court in Beijing. His plan seems to have been first to evangelize China, and then resume his mission in Japan. Such a course of action might strike us today as being simplistic. Did Xavier really think he could accomplish this task so readily? His naïveté is apparent, but so is his zeal. For Xavier, no barrier was insurmountable-be it linguistic, cultural, or geographic-in the mission of evangelization. The following excerpt from a letter about China shows his boundless energy and aspirations: “Nothing leads me to suppose that there are Christians there. I hope to go there during this year, 1552, and penetrate even to the Emperor himself. China is that sort of kingdom, that if the seed of the Gospel is once sown, it may be propagated far and wide. And moreover, if the Chinese accept the Christian faith, the Japanese would give up the doctrines which the Chinese have taught them” (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1552xavier4.asp). It was precisely a letter such as this that would stir the zeal of generations of would-be missionaries.

Yet problems abounded, including the fact that China was closed to foreigners. Xavier tried to get himself named as a papal ambassador. The plan failed. Xavier then tried to get smuggled into China on a boat. This attempt also failed. The boat never showed up and Xavier died of exhaustion in Shangchuan, a small island just off the coast of mainland China.

Much of Xavier’s story is widely known. In fact, Franz Schurhammer wrote a four-volume biography of Xavier which has been translated into English. It is a painstaking and magisterial account of the life of the saint. Indeed, it is one of the most detailed biographies of all time. Another great source is the Letters and Instructions of Francis Xavier, translated by M. Joseph Costelloe and published by the Institute of Jesuit Sources.

In the thirty years after Xavier’s death some fifty missionaries-Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians-tried to gain entry into China. Some embarked from Macau (Macao), which had been made a Portuguese trading post in 1557. Others set out from the Philippines. Often enough, their goal was to reach Canton or even coastal Fujian Province. However, since China was still off limits for foreigners, they risked imprisonment. In fact, none of these missionaries were able to establish a permanent base inside China. The most they could hope for was to work for the release of European prisoners in Canton. Others did pastoral work mainly with European, often Portuguese, sailors and merchants in Macau. It was in Macau that the Jesuits established a permanent residence, as well as a school and a church. (In fact, to this day one can still see the façade of St. Paul’s Church.) But the establishment of a permanent Christian presence in China would need to wait.

III. Matteo Ricci and the Christian-Confucian Dialogue

In 1552, the same year that Francis Xavier died in Shangchuan, Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) was born in Macerata, Italy. To this day, in both East and West, he remains the best known Jesuit missionary to China.

Ricci arrived in China in 1583, guided by Michele Ruggieri (1543-1607), who had already made a successful entry into China. They had already secured permission to establish a residence in Zhaoqing, a small city upriver from the bustling port of Canton. It was from Zhaoqing that Ricci began his 18-year “ascent” to Beijing.

Ricci took his cues from and further refined the mission methods of Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606), who, in 1572, had been named the Visitor of the Jesuit missions in the East Indies. In this role, Valignano became the architect of a policy of missionary accommodation. In time, in China at least, this policy would come to mean that missionaries were to learn Chinese in order to dialog with the literati and to read the Chinese classics, to value China’s time-honored customs and culture, and to use Western science and technology as a method of attraction. The policy would also come to be associated with a top-down approach, whereby missionaries were to focus their efforts on the elite, in the hopes that this work would then trickle-down to the popular classes.

The story has been widely told. Ricci first wore the garb of Buddhist monks. Little did he know that Buddhism had been in decline for some time in China. He soon realized his mistake and recast himself as a Confucian scholar, a choice which would hopefully make him more credible with the leading officials. In this capacity, he set about mastering Chinese, which he did, even to the point of delving deeply into the Confucian classics, and being able to dialog with leading officials. With much help, he translated many western scientific works into Chinese.

Ricci’s own mission methodology is best exemplified in his most well-known book, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. Ricci structured this book as a dialogue between two scholars, one from the West and one from China. They both speak generally about questions of human existence. It is only at the end that the Western scholar mentions the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. Ricci knew that to begin with the passion accounts would offend Chinese sensibilities, especially among the literati. A crucified God would have shocked them. Ricci would only tell the Chinese about the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus after they had been adequately prepared.

What was Ricci like? Was this top-down approach correct? Was this his only approach? These debates occupy scholars today. They are also some of the issues that R. Po-Chia Hsia takes up in his 2010 work A Jesuit in the Forbidden City: Matteo Ricci, 1552-1610. Hsia is a deft guide, one who is uniquely capable of describing “the story of Matteo Ricci and his world.” Hsia is, by training, a historian of Early Modern Europe, a subject area on which he has written extensively. With this background, he is a natural fit to study Ricci. For Hsia has mastered not only the key European languages, but classical and modern Chinese as well. This allows him to probe the most important sources and archives relating to Ricci: the Fonti Ricciani by Pasquale D’Elia; the works of Pietro Tacchi-Venturi; the Jesuit China Archives in Rome; the 18-volume Documenta Indica, (1540-1597); and the official history of the Ming dynasty. Hsia is thus able to bring his considerable talents to bear on the subject of Matteo Ricci, a man who symbolizes the meeting point of East and West.

Hsia’s work is a delight to read not only for its breadth of knowledge, but also for the elegance of its prose. For example, describing Ricci’s world, Hsia says: “Born into a world torn asunder by the Protestant Reformation, he departed a Catholic Europe renewed in strength, restored in confidence, and restless in combat, against heretics and infidels, enemies of the Roman Church.” On Ricci’s project, Hsia writes in the prologue: “By his intelligence, charm, and endurance, the Italian missionary gained access into the inner realm of Chinese civilization, denied to almost all visitors. To use a metaphor of the Jesuits, he had hoped to enter the house and compel its residents to exit with him in allegiance to the Catholic faith.”

While Ricci and other Jesuits were set on increasing God’s glory in places like China, they, at times, overstated their case. Hsia is sensitive to this fact. For Ricci led some Chinese scholars to believe that one of the reasons for the success of Christianity was that Europe was without war for 1600 years! Hsia himself notes that he has recently become interested in things “Jesuitical.” Surely he knows this adjective has multiple meanings, not all of them complementary. I find this apt because, while he is respectful and even laudatory of Ricci, he is not above calling into question some of Ricci’s legacy. Perhaps Ricci was not above being “Jesuitical” himself.

In the book, Hsia traces Ricci’s life from his birth in Italy, to his entrance into the Jesuits and his studies at the Roman College, to his inspiration and perception of a missionary call, to his departure from Portugal and his arrival in Macau in 1582, and finally to his successful entrance into the mainland and his long journey to Beijing. It was in Beijing that he was able to work near the center of imperial power. Hsia also has a chapter on Ricci’s The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. His epilogue deals in greater depth with the historiography of Ricci scholarship.

In his text, Hsia explains why Ricci, even 400 years after his passing, remains a compelling figure today. In Hsia’s estimation, part of the reason is due to the good public relations of fellow Jesuits. After all, they propagated the “master missionary with the master narrative.” And Hsia notes: “There is something irresistible in this narrative: by virtue of his intellect, a heroic individual bridges impossible chasms between civilizations, opening up a new world of understanding by the strength of his learning and genius.” Indeed, this is a fitting coda to Ricci, widely known in the West, and one of a few foreign missionaries still held in the highest esteem in China today. In fact, Ricci was the first foreigner in China to be given an imperial burial. Even today one can visit his tombstone at the Zhalan cemetery on the western edge of old Beijing.

IV. The Generation of Giants: Jesuits at the Court and in the Provinces

Other illustrious Jesuits followed in Ricci’s footsteps. Ricci and these others have been immortalized by George Dunne as the “generation of giants.” In fact, the contributions of Ricci’s generation and after can be divided into two major groups. The first group was those who labored in the Beijing court or with other members of the elite. These Jesuits employed a top-down approach. They were convinced that even if the faith never made it outside of elite circles, they could still consider their mission a success. This is because, according to Hsia, “Ricci thought it better to have a small, high-quality Christian community than a large multitude.” The second group of Jesuits was more involved in direct pastoral work in the countryside. They employed a bottom-up approach by focusing on the popular classes at the grassroots level. All told, according to Hsia, the number of Jesuits who labored in both groups numbered some 500 Jesuits between Ricci’s death and the suppression of the Jesuit order in 1773.

Let us first take up the contributions of the court Jesuits. Many of them would eventually be buried with Ricci as a sign of imperial favor. These missionaries made it to China in the first place through the efforts of Nicolas Trigault (1577-1628). In fact, it was Trigault’s On the Christian Expedition in China-a work which relied heavily on Ricci’s letters-which publicized far and wide the work of the Jesuit China mission. The book was a major success, especially in Jesuit circles. With such deft use of publicity, Trigault was able to recruit capable Jesuits for the China mission. They, in turn, were followed by many others. Trigault himself made other contributions as well. He got permission to translate the Bible into literary Chinese and to use the Chinese language in Mass. (Permission was given for a mass in Chinese, but, by the time it was given, it was too late to put into effect.) In sum, according to Hsia, Trigault “propagated the Riccian legacy” and was “the spokesperson of the Jesuit China Mission.”

Let us briefly describe the contributions of some of these Jesuits, both those recruited directly by Trigault, and others as well. A wonderful resource for much of this history is the Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635-1800, edited by Nicolas Standaert, and published in 2001. This book, nearly 1,000 pages in length, although not inexpensive, is indispensable for the researcher interested in the early years of Christianity in China. One article alone, by Nicole Halsberghe and Keizô Hashimoto, discusses the work of the Jesuit astronomers in China. The earliest of these astronomers was Adam Schall von Bell (1592-1666). Having been recruited by Trigault, he left for China in 1618 along with 21 other Jesuits. So dedicated was he to his mission, that he brought with him an entire science library. He ultimately wrote many treatises for the emperor, and he became a first class mandarin and the President of the Mathematical Tribunal.

Schall also worked at the Bureau of Astronomy, which he directed from 1645 to 1664. As such, he was responsible for transferring much European astronomy to China. It was in this role that Schall and other Jesuits aroused antipathy within the court. It seemed clear why the foreign presence at the court was resented. For, as Halsberghe and Hashimoto note, the Jesuits “were in charge not only of the calendar, but also of the calculations and predictions needed to perform rites properly.” The performance of these rites was crucial in the smooth functioning of the government. But it offended some at the court that foreigners had such an important role in matters touching so closely on Confucian philosophy and matters of state. Thus, the Jesuits became embroiled in the famous “calendar case” when a certain Yang Guangxian brought the Jesuits to trial. They were accused of choosing an “inauspicious” date for the funeral of a prince (718). Schall was sentenced to death. In time, however, Yang’s own calendar was questioned, and Schall and the more accurate Western method of calendrical calculation were exonerated.

Ferdinand Verbiest (1623-1688) was then made Vice-Director of the Bureau of Astronomy. In this capacity, Verbiest is best known for continuing the work on the calendar and for building astronomical instruments that were used at the observatory. (Some of these instruments can still be seen in Beijing today.) Verbiest also revised astronomical compendiums, and he even helped to cast cannons for the Chinese government.

Ricci, Schall von Bell, and Verbiest, are among the most well-known, but a host of other Jesuits also had impressive accomplishments. For example, there is the striking story of Bento de Góis (1563-1607), a Jesuit brother, who traveled overland to China from the court of the Great Mogul Akbar in current-day Afghanistan. He thus followed in the footsteps of Marco Polo and showed that China was the same place that medieval Europeans called Cathay. Luigi Buglio (1606-1682) translated into Chinese important liturgical books such as the Roman Missal and the Roman Breviary. Martino Martini (1614-1661) published an atlas of China. Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was an influential court painter. (For further information on some of these Jesuits, see Thomas F. Ryan’s 2007 short popular account simply titled Jesuits in China. A helpful online resource is the New Advent website.)

Up to this point, as we have seen, most of these Jesuits were from Portugal, Italy, Belgium, Germany or Switzerland. They were all part of the Portuguese Vice-Province and worked under the protection of the Portuguese Padroado. This status quo was soon to change. For it was Verbiest himself who wrote a letter requesting more Jesuit astronomers. An article by Claudia von Collani in the Handbook explains that Louis XIV responded to this request and sent French Jesuits as the “King’s mathematicians.” Five of them reached China in 1687. Thus began the French Jesuit mission. By 1700 this mission had its own superior and plot of land, and was made independent from the Portuguese Vice-Province. The French mission still had to answer to the delegate of the Jesuit superior general. Yet efforts to bring the French mission under the Vice-Province failed.

The French Jesuits were highly successful. Many of them worked at the court: some were tutors to the emperor; some were engaged in astronomy; and some worked on cartography. Regarding cartography, von Collani further explains that they began this work in 1708 and finished ten years later. These Jesuits traveled throughout China and eventually produced an atlas of the realm, the result of which was that China was now “better mapped than Europe” (315). Interestingly enough, some French Jesuits went beyond missionary accommodation and tried to harmonize biblical accounts with ancient Chinese history. Some tried to show that “religion in ancient China and Christianity were in principle the same” (315). The more radical among them were called Figurists, because, as von Collani notes, they often used typological exegesis to discover-what they believed to be-intimations of Christianity in the Confucian classics. The hope was that Chinese Christians now had a way “of preserving their tradition without having to refer to Judea” (669). Some Figurists even believed that some Chinese characters had an originally religious meaning. For example, the character for heaven-it was conjectured-was a composite of the characters for a human being and the numeral two. It thus referred to the second person of the Trinity!

All told, these French Jesuits also acted as mediators between China and Europe. They not only brought western science and technology to China, but they propagated their impressions of China to a European audience as well. One of the best known of these French Jesuits was Antoine Gaubil (1689-1759) who was not only an astronomer, but a historian and a translator of Chinese books as well. Many of their impressions, including those of Gaubil, were sent back to Europe by way of letters which have come down to us as the Lettres édificantes et curieuses (Edifying and Curious Letters). They describe the Jesuit mission and the Chinese situation in great detail. (Some of these letters can even be found online at http://www.archive.org.)

Let us now turn to those Jesuits that worked in the provinces. The fact is that even during Ricci’s time, there were Jesuits laboring far from the court. In fact, the over-emphasis on Ricci is now being corrected by scholars such as Liam Brockey, who in his prize-winning book Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724, makes a strong case that: “An exaggerated emphasis on Ricci and his successors in Peking, a view that has long characterized histories of the mission, has almost completely overshadowed the work of…[other Jesuits]…who were busy propagating Christianity at the Jesuits’ other residences” (51).

It was precisely at the other residences that the Jesuits had more time to engage in direct evangelization. These efforts bore fruit. In the region around contemporary Shanghai, they were able to introduce the Marian Sodalities, and other such devotional groups, which were quite effective in recruiting local Christians, and channeling their energies on behalf of the church. Some of them were inaugurated as early as 1609, one year before Ricci’s death.

Brockey also gives the telling example of Giulio Aleni (1582-1649) who traveled to distant Shanxi Province, and then to coastal Fujian Province where he founded a mission. (The history of Aleni’s work in Fujian along with later developments under the Dominicans can be found in Eugenio Menegon’s excellent 2009 book Ancestor’s, Virgins and Friars: Christianity as a Local Religion in Late Imperial China.) Aleni is responsible for authoring dozens of books including: an illustrated life of Christ, a manual on how to make a good confession, a life of the saints, and a popular catechism for children. This latter work was based on the Four Character Classics, which were popular primers for elementary school students. It was inculturated Christianity at its best: Chinese in form, and Christian in content.

In sum, the Jesuit mission methodology was bearing great fruit. Yet, it was not without its detractors.

V. The Chinese Rites Controversy and the Decline of the Jesuit China Mission

The Jesuits’ accomodation to Chinese culture and their mission method were bearing fruit. Yet, when other missionaries, such as the Dominicans and Franciscans, came to China, they were not comfortable with some of the Jesuit accommodations. Thus began the Chinese Rites Controversy, which absorbed the energies of the Church for nearly one hundred years.

A concise guide through this extraordinarily complex and freighted history is still Francis Rouleau’s 1967 article in the New Catholic Encyclopedia. I will rely heavily upon his account. Rouleau calls this controversy “among the most momentous” in the history of Christianity. For the sake of simplicity, he divides his treatment into two important parts. First, he defines the Chinese rites. Second, he describes the controversy between the Jesuit position and the position that the Vatican would eventually take.

In defining the rites, Rouleau describes three related issues. First, there were the Confucian ceremonies that the scholar class periodically held in temples and halls dedicated to Confucius. This class was duty-bound to honor Confucius much like, in today’s world, a civil or military official will salute the flag or sing the national anthem.

Second, there was the “cult of the familial dead”, which “was manifested by the kowtow, incense burning, and serving food before the grave.”

Third, there was the “term question.” This revolved around the vocabulary the missionaries used to explain Christian concepts. For example, given the choice between introducing foreign words, or using Chinese words to describe God, the Jesuits chose the latter. This implied that the Confucian classics-where they found these terms-had a monotheistic view of God.

After mastering Chinese and reflecting deeply on the Confucian classics, Ricci made a decision in 1603 which argued that the rites in honor of Confucius were civil, not religious acts. Second, honoring the dead was “perhaps” not superstitious, and he permitted them. Therefore, these two specific rites could be isolated from what other Christians might call a “pagan” or “superstitious” environment. Finally, the Chinese terms Tian (heavens) and Shangdi (Lord above) were permissible to describe the Christian God. All told, Ricci felt that permitting these ceremonies was a necessary requirement for large-scale conversion. Since these rituals and terms were fully embedded in the Chinese social and cultural context, Chinese converts should be permitted to continue using them. They need not cease being Chinese by becoming Christians.

Others were not convinced. Already by 1631, Dominicans were arriving on the scene, and the Franciscans returned in 1639. Some of them felt that the Jesuits were permitting idolatrous practices. In 1643, a Dominican went to Rome with some questions. Thus began what has become known as the Chinese Rites controversy. The Vatican first argued for the Dominican position. Then a Jesuit went to Rome and clarified the situation. Pope Alexander VII accepted the Jesuit understanding in 1656. The rites “as explained” were then permitted for the next 50 years. In fact, during these years, Chinese emperors continued to be happy with the Jesuits and their work at the court. The high water mark was reached in 1692, when Emperor Kangxi granted the Edict of Toleration which permitted Christian missionaries to preach throughout China. Thus, the missionaries now had imperial blessing as well.

Yet, the controversy would not die down. In 1693, Charles Maigrot, the vicar apostolic of Fujian, once again called the rites into question, and, according to Rouleau, “the Holy See became involved in a judicial process of extraordinary complexity.” The Vatican now had to determine whether the rites were compatible with Christian doctrine. In doing so, it had to try to understand their role within the utterly foreign Chinese cultural context. Special church commissions were convoked from 1697 to 1704. Finally, in 1704, the Vatican reached a decision.

The key points of the 1704 decree were the following: It forbade the use of Tian and Shangdi for God. It also forbade ceremonies to honor Confucius and to honor ancestors. Even so, “a simplified commemorative name tablet” of the familial dead was permitted in Christian homes. This is what the decree did do. What it did not do was to determine whether the 1656 Jesuit explanation of the rites was true or misleading. Further, it made no statement as to the validity of the Confucian classics. This was beyond the competence of the Church authorities. The decree, then, simply stated that the rites were incompatible with Christianity. It made no further judgment on the validity of the Confucian philosophical system. Therefore, it argued against the Jesuit viewpoint that these practices could somehow be isolated or even purified from the “superstitious” Chinese cultural context. In other words, except for a few minor concessions, the rites would no longer be permitted.

As one might expect, this decision angered Emperor Kangxi, who had himself stated that these rites were civil in character. He took further umbrage that Europeans would dare explain to him the nature of Chinese practices. He then demanded that if the missionaries wanted to continue their work in China, they needed to obtain a certificate stating that they agreed with Ricci’s methods. Likewise, the Church also demanded its own oath of compliance. Thus, especially after 1707, mission work in China became especially precarious. The combined rulings of the emperor and the Vatican left missionaries in a bind. Should they obtain the certificate or sign the Church oath? Should they abandon China altogether? Should they stay on illegally? Should they stall for more time? A great irony in all of this is that these rulings were made when the missionary presence was larger than ever. For, at this time, the number of foreign missionaries, from all the orders that had congregations, had peaked at about 140.

Yet, for all of them, the situation became increasingly tenuous. The Vatican followed up with a further decree in 1715, and one in 1742 which definitely closed the controversy. In addition, in 1724, Kangxi’s son, Yongzheng, outlawed Christianity as a “perverse sect.”

Yet even under Yongzheng, some priests were permitted to stay on in Beijing. They put in long days of service at the court. They thus tried to create goodwill between themselves and the emperor. The hope was that this goodwill would take the pressure off those missionaries and Chinese priests that continued to labor in the countryside.

This was not the end. In a complex test of wills between the papacy and European governments, the Jesuit order itself was suppressed in 1773. The stream of Jesuit missionaries to China dried up. Further, those Jesuits that remained in China, both foreign and Chinese, now technically labored as diocesan priests. A notable example was Gottfried von Laimbeckhoven (1707-1787) who worked in the provinces. He ultimately became bishop of Nanjing and even administrator of the diocese of Beijing. However, for all intents and purposes, the Jesuit China mission collapsed.

These were also dark years for the Church as a whole. The Enlightenment had called into question faith itself; the French Revolution ushered in a period of Church persecution; and the Napoleonic wars caused chaos throughout Europe. In sum, the upheavals in Europe affected Catholic missions worldwide.

In the 250 year history of the “old” Society, the Jesuits had left their mark. They had served emperors, brought in key scientific information, dialogued with top officials, served at the Bureau of Astronomy, baptized Christians, and put the local church on a solid footing. When Jesuit efforts are combined with the work of others, both local and missionary, the sum result is impressive. For, even in the troubled late 18th century, the number of Catholics in China-by many accounts-surpassed 200,000.

Would these local Christians weather the storm? Would the Society of Jesus be restored? Would the Church itself revive and send out missionaries? We will explore these issues in the second part.